Spotify is in the spotlight as its proposed direct listing tests the market for unusual financing. Private companies are watching the outcome—especially as markets turn volatile.

A year ago, the global market for initial public offerings (IPOs) was just starting to heat up. Thanks to strong growth in Europe and North America, overall deal volume last year increased 45%, while capital raised was up by 35% to $144 billion, according to Renaissance Capital, a money-management and institutional research firm. Asia-Pacific led all regions, with a 40% share of new capital raised, down from 57% in the prior year. Excluding the Chinese A-share market—accessible only to Chinese investors—the average return on global IPOs was 16%, about level with the previous year.

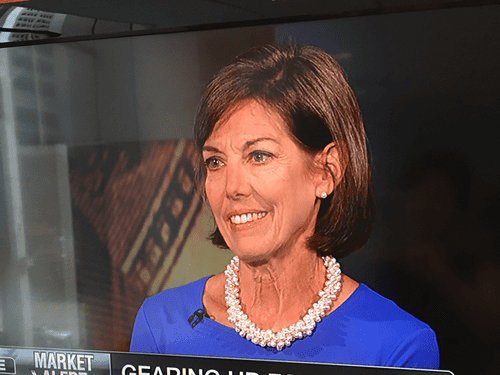

“It was a decent market in 2017, with issuance picking up and investors experiencing good returns,” says principal Kathleen Smith, manager of IPO ETFs at Renaissance, which focuses on the global IPO market.

It was under those conditions that Spotify, the Swedish music-streaming business, initiated plans for a direct listing on the New York Stock Exchange. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently approved rule changes for the exchange that enable the listing. Spotify could potentially list its shares for trading within weeks.

Other large, private companies are watching with interest, though recent market volatility dampens Spotify’s prospects for success. If the correction is short-lived, however, scores of so-called unicorns (private companies worth more than $1 billion), in the US and China particularly, may test the public markets. Candidates for potential offerings in the near future include Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi and online wealth-management company Lufax. Tech firms in the US such as Airbnb, Pinterest and Uber could also come to market. Other deals already in the works include Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil producer; Chinese state-owned wireless infrastructure company China Tower, and Siemens Healthineers, the German company’s healthcare business.

Many potential IPO candidates, however, may be content to stay private. Not only are the public markets more heavily regulated post-financial crisis, but there is also no shortage of capital available in the private markets to fund growth. Early investors and employees might want to sell some of their holdings, but private companies—particularly tech unicorns—seem in no rush to sell shares to the public. “Most of the unicorns don’t need capital,” says Anna Pinedo, co-head of the Global Capital Markets at Mayer Brown. “There is still plenty available in private placement rounds.”

Not for everyone

Most private companies, however, would like a publicly traded stock, to compensate employees and make acquisitions easier. A potential alternative to a full-on public offering is what Spotify plans to do: simply list shares directly on an exchange.

Unlike a traditional IPO, a company undertaking a direct listing does not issue new shares to the public. It doesn’t have to produce a prospectus or go on an extended road show to drum up investor interest. There is also no dilution or lock-up period for existing shareholders from a new offering. The company still has to undergo the registration process with regulators—in Spotify’s case, the SEC—but it doesn’t also need an underwriting group to support the offering. The process costs less, takes less time and saves companies from having to raise money at a discount—possibly a bigger concern in the market now.

“Most companies want the support from underwriters to help tell their story, provide research coverage, establish a valuation and provide liquidity post-deal,” says Pinedo. “But for well-known companies that don’t need capital and want to provide liquidity to their investors, this is a potential alternative.”

Direct listings aren’t new, but so far they have been limited to small-cap companies predominantly in the biotech and life-sciences industry. Their public lives haven’t gone well. None of the four biotech firms that did a direct listing on the Nasdaq exchange have share prices above where they initially started trading.

Spotify, however, is a different animal. With 70 million subscribers, the company is a household name globally. It was valued at roughly $20 billion in its latest round of private fundraising, although full details of the deal weren’t disclosed. If Spotify’s listing goes smoothly, other large, well-known firms may follow suit. “If there’s clear evidence that the direct listing is a win/win for Spotify and new shareholders, I wouldn’t be surprised to see other similar companies try the same approach,” said Rohit Kulkarni, managing director of private investment research at Sharespost, which provides a platform that has helped over 150 private companies execute shares transactions. “Direct listings could be viable for a number of high profile candidates.”

Smith believes that Spotify’s pioneering approach to going public was born of desperation. “We think Spotify has opted for a direct listing because of problems with its capital structure,” says Smith. “No company in their right mind would have done this.”

Checking With Other Stakeholders

The problem has to do with a round of fundraising the company executed in 2016 with private-equity investors TPG Capital and Dragoneer Investment Group. The investment was in the form of convertible bonds with conversion terms reportedly tied to an IPO price. The longer Spotify takes to come to market, the worse the terms get on the conversion.

Meanwhile, Tencent Holdings, the giant Chinese tech conglomerate, bought some Spotify shares from existing holders last year at a reported valuation of $20 billion. Some of the shares were owned by two private equity firms, though details were not disclosed. “We’re trying to read the tea leaves on this,” says Smith.

She believes that Spotify is running the risk of a messy listing without the help of underwriters to value the company. The worst outcome for companies is a busted listing—one that can’t sustain its price in the first three months of trading. “It’s very hard for a company to get back on its feet if that happens,” says Smith. She thinks Spotify may have to institute a lock-up on shares to manage the selling that could occur. “There is such a thing as being penny wise and pound foolish.”

While the idea of going it alone without the support of investment bankers may be attractive to companies, it’s less so to the institutions that invest in new listings. “Investors haven’t forgotten the dot-com bubble,” suggested Smith. “They’re a lot more concerned with overvalued private companies coming to market.”

That may be the biggest reason for a global IPO market that is still a shadow of its former self prior to the dot-com bubble. A successful direct listing by Spotify that encourages more private companies to list their shares would be good for the capital markets, argues Pinedo. “From a public-policy point of view, it’s important for companies to be attracted to the public markets,” she says. “Every alternative is worth considering.”