In late June, when women are finally allowed to drive in Saudi Arabia, many observers predict an uptick in economic activity.

Beginning on June 24, when the ban on female drivers in Saudi Arabia is lifted, more women are expected to enter the workforce, helping to fulfill a goal of the kingdom’s Vision 2030 program of reforms.

“This is clearly a positive step for women’s rights,” says Jason Tuvey, Middle East economist at Capital Economics, “and it could have a significant economic impact by increasing the very low female labor force participation rate and potentially boosting GDP growth.”

Some Saudi women have already benefited from the kingdom’s growing acceptance of women in new roles, rising to prominence in a variety of fields. In 2013, Bayan Mahmoud Al-Zahran became the first female licensed lawyer in the kingdom and founded the country’s first female law firm. Khawla Al Khuraya, a physician, is director of the King Fahad National Centre for Children’s Cancer and Research. Saudi Aramco has a number of women in its top ranks, including Nabilah Al-Tunisi, chief engineer, and Huda Al Ghoson, executive director of Human Resources. Hayat Sindi, a biotechnologist, was among the first women to be appointed to the country’s consultative assembly, the Shura Council. Haifaa Al-Mansour is Saudi Arabia’s first female movie director.

“There is no doubt that the developments taking place in the kingdom, specifically in terms of stimulating the role of Saudi women, have removed many barriers—including psychological ones,” says Rania Nashar, CEO of Samba Financial Group. “They are encouraging young women to explore new roles in the economic and commercial landscape.”

Early evidence suggests many Saudi women are eager to enter the workforce and to have careers outside of the home. The Saudi General Directorate of Passports said it received 107,000 job applications from Saudi women in one week after it listed openings on its website for 140 positions for females at airport immigration.

Today in the Middle East and North Africa, women contribute only 18% of GDP, according to the McKinsey Global Institute. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region alone, bringing each country up to the best regional standard for female participation in the workforce would add $180 billion to the economy in 2025. Full parity in the rates of male and female participation would increase that amount to $830 billion, McKinsey says.

“If lifting the ban improves the global perception of Saudi Arabia, it may entice greater foreign investment, which is low by international standards,” Tuvey says. “Weak foreign investment has limited the boost to productivity from the adoption of new technologies and production processes readily available elsewhere.”

Homegrown Talent

As part of its efforts to reduce Saudi Arabia’s reliance on some 9 million foreign workers by employing more local men and women in the private sector, the government plans to limit certain retail jobs to Saudi nationals. The Ministry of Labor and Social Development has released a list of 12 sales jobs that will be off limits to expats come September 2018. These retail categories include cars and motorcycles, auto parts, building materials, carpets, home and office furniture, kitchenware, electronic appliances, children’s clothing and men’s accessories. The ministry has begun arresting expatriates caught working in nationalized sectors and warned violators that they could be deported.

More than 200,000 Saudi women already are working in the retail sector. Since January 2012, only females have been allowed to sell women’s lingerie. Since then, other categories have been added, such as cosmetics, abayas (loose black robes required to be worn by women) and wedding dresses.

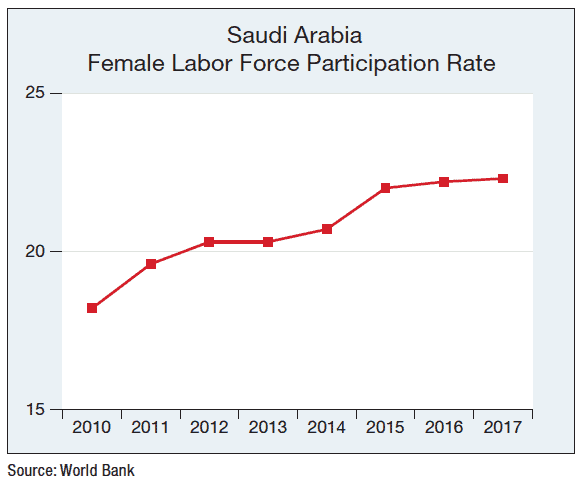

Vision 2030 aims to increase female participation in the workforce from about 22% at present to 30%. Along with “our lively and vibrant youth,” the 2030 program document says, “Saudi women are another great asset. We will continue to develop their talents, invest in their productive capabilities and enable them to strengthen their future and contribute to the development of our society and economy.”

One survey by Kantar TNS research agency found that 82% of Saudi women are contemplating getting a driver’s license. PwC Middle East says the number of female drivers is projected to reach 3 million in 2020. One beneficiary will be the auto insurance market, which is expected to grow by 9% annually, reaching $8 billion by 2020, PwC says. Toyota and Hyundai, which sell the most cars in Saudi Arabia, could also be among the winners. With more cars on the roads, highways will need to be expanded, as they are already notoriously congested.

Lifting the ban on female driving will save families the cost of paying drivers, but is unlikely to have an immediate impact on the female unemployment rate, according to a study by Oxford Economics and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales. To be more effective, the study says, the wage gap between Saudis and foreign workers in the private sector must be narrowed. Saudi workers earn four times as much as expats in the same jobs.

Cracks in the Ceilings

Nevertheless, there remain hurdles to the full empowerment of women in Saudi Arabia. The Saudi system of male guardianship, whereby a woman is required to have her husband’s consent in order to travel abroad, make legal claims or obtain financing, is certainly one of those hurdles. According to Human Rights Watch, dozens of Saudi women have told them that the male guardianship system is the biggest impediment to realizing women’s rights in the country, since it treats adult women as legal minors. And while more than half of all university graduates in the country are female, there remains risk there, too. “Having given ground on [the driving] issue, the religious establishment may try to reassert its authority on other reforms, such as changes to the education system,” Tuvey notes.

Cracks are beginning to appear in the system, however. In April 2017, King Salman issued an order to all government agencies that women should not be denied government services simply because they do not have a male guardian’s consent. This February, women were granted permission to open their own businesses without the consent of a husband or male relative.

The kingdom’s glass ceilings are being shattered, with accomplished women setting examples from the highest heights. In finance, Sarah Al-Suhaimi became the first female chair of Saudi Arabia’s stock exchange, the Tadawul, at about the same time that Rania Nashar rose to CEO at Samba. Al-Suhaimi remains CEO of the investment-banking unit of National Commercial Bank, NCB Capital. Latifa Al-Sabhan was appointed chief financial officer of Arab National Bank (ANB), a major Riyadh-based bank, which is 40% owned by Arab Bank.

“Women are moving forward with confidence,” says Nashar, “and taking their rightful place in the workforce and wider community.”