YIELDING STATE CONTROL

By Arthur Clennam

Breaking the monopoly of China’s big banks is only an idea for now, but one that the government knows it cannot ignore.

Premier Wen Jiabao, second-most-powerful member of China’s standing committee of the politburo, took a poke at China’s banks in early April, saying the country needed to break the monopoly that allows the big banks to pay almost nothing for deposits while pricing loans high.

“Frankly, our banks make profits far too easily,” the premier said. “Why? Because a small number of major banks occupy a monopoly position, meaning one can only go to them for loans and capital.”

There are good reasons to discount these statements as mere political show. As Gordon Chang, a noted critic of China’s ruling elite and the author of The Coming Collapse in China , points out, Wen has been premier since 2003 and is China’s top economic policymaker. Who is more responsible for the state bank monopoly than he?

Chang and others have noted that the statement played well in a transition year in China: The changing of the guard, with presumed new leaders Xi Jinping becoming president and Li Keqiang becoming premier, is scheduled to take place in the fall. The Communist Party is under attack for a widening divide between rich and poor, between the politically connected elite and the untold masses of people that strive to rise into that group.

Using banks as a sham scapegoat plays well in countless villages and industrial boomtowns. It also gives the standing government a decidedly populist tinge at a time when scandals surrounding Bo Xilai—the former Party head in China’s largest city, Chongqing, who was sacked in early April—and Chen Guangcheng—the blind legal activist who sought US diplomatic intervention to study abroad—has raised gnawing doubts in the Party itself over its populist credentials.

But there is certainly more to it. Premier Wen would never have made such a statement if it didn’t reflect a body of opinion in China’s ruling elite. Like Eisenhower’s 1959 attack on the “military industrial complex” that he helped build, Wen made use of an existing position of reform already building momentum in the capital to boost his own populist credentials.

NEED FOR BANKING REFORM

Paul Cavey, an economist with Macquarie Bank in Hong Kong, says that discussion of real banking reform has long been a feature of economic policy debate—at least since the onset of economic tightening that began in 2010, following runaway growth on the back of China’s 2009, $600 billion economic stimulus package. Government tightening of state banks’ capital-reserve-rate ratio made money far more expensive even for state-owned operations.

For China’s booming but nascent nonstate sector, particularly small and medium-size companies, it was worse. They faced loan rates well above the 6% advised by the People’s Bank of China or were cut off from bank loans altogether.

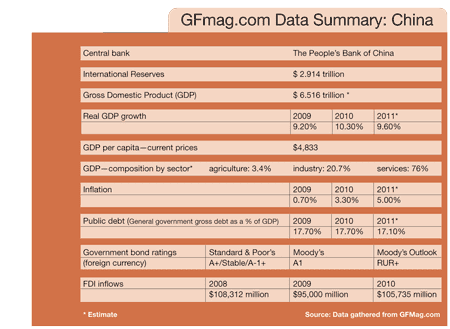

Banks controlled by the state hold about 72% of the nation’s banking assets, according to a study by Andrew Szamosszegi and Cole Kyle of Capital Trade, a Washington think tank. Among these, China’s big-four banks—Industrial Commercial Bank of China, China Construction Bank, Agricultural Bank of China and Bank of China—hold about 48% of assets, while “policy banks,” such as the Export-Import Bank of China, hold about 9%. Joint stock commercial banks, with the state as the largest shareholder, hold about 15%. The rest is held by privately owned banks, credit unions, foreign banks and other nonstate financial institutions.

EXPANDING SHADOW BANKING

The tightness in lending led to a ballooning shadow banking market, in which businesses and consumers use unregulated instruments for funding and investments. This market features instruments such as held-to-maturity assets, which resemble an untradable bond held until its term expires. Company borrowers don’t list them as liabilities on their balance sheets, because accounting standards require that an instrument be classified as debt or equity securities, and they qualify as neither. Nor do the lenders that hold such assets show interest payments on their accounts.

Estimates of the size of this shadow banking system vary. Ren Xianfang, an economist with IHS Global Insight, pegs it at $1.7 trillion, or close to the size of the 2011 US deficit. China’s state-owned banks actually contribute to the size of this market by acting as intermediaries for so-called wealth management products through nonbank subsidiaries. They collect fees for these products, but take no balance sheet risk.

One way to reduce the size and influence of this market would be to expand legitimate fundraising and investment options in the capital markets. This would also reduce the influence of state-owned banks without necessarily breaking up their monopoly. May Yan, a banking analyst at Barclays Capital in Hong Kong, says that the only feasible way to reform is “to have the non-state-bank sector grow larger. In the end it would mean the big banks get a smaller part of the entire market, with growth in both non-state-owned banks and capital markets.”

BUILDING A BIGGER BANK MARKET

There is precedent for expanding such options. Japan expanded its bond market in the 1980s. This eventually led to a leaching of market share from the banking system, but in a counterintuitive manner. Investment banks tended to underwrite bonds for the banks’ existing big customers, who began to rely for funding on the bond market, rather than commercial banking. This forced banks to seek customers outside the traditional keiretsu (business group) in a quest to restore profits. “It’s not clear in Japan that this led to an improvement in the quality of lending,” says Cavey. A similar process that drove banks to provide more attractive services to the nonstate sector in China “would [not] guarantee any lending discipline either,” he says.

A Japanese-style transition is taking place in China, but slowly. The domestic bond market is big—estimated to be $3.5 trillion at the end of 2011, according to Reuters (in the US, the figure is $36 trillion), with new issuance totaling $1.2 trillion in 2011. Still, government bonds and central bank bills accounted for 40% of all issuance, and another 20% by policy banks. However, nonfinancial firms accounted for 28% of all issuance in 2011, up from 17% in 2010.

“Continental capitalism, in which the banks have greater control of a nation’s vehicles of finance, is admittedly tainted in the public’s eye by the current crisis. But it provides for a more balanced, less volatile pattern of growth, if you look at its record since the 1950s”

– Michael Pettis, Peking University Guanghua School of Management

Cavey believes that capital markets expansion will only gloss over the problem. True reform would require interest rate liberalization. This has been bruited for many years in government planning, but is almost certainly off the agenda until after the leadership transition.

Interest rate liberalization would allow the big banks to compete for deposits and have greater leeway in pricing loans. A more competitive market would tighten the spread between deposit rates and lending rates, reducing bank profits and squeezing capital.

However, poor quality lenders would suffer, and perhaps face liquidity concerns. No one in Beijing wants to see a return to widespread bank asset woes that the nation experienced in 1998 and 2003. This fear could keep any meaningful action in check indefinitely.

Michael Pettis, a professor at Peking University Guanghua School of Management and senior associate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, also cautions against the idea that China has only one possible path to financial sector reform—toward a US-style system. “If you look at the US model, it works, but at the price of tremendous volatility. The system accepts higher risk for transparency and for the market-based approach,” he says.

“Continental capitalism, in which the banks have greater control of a nation’s vehicles of finance, is admittedly tainted in the public’s eye by the current crisis,” Pettis adds. “But it provides for a more balanced, less volatile pattern of growth, if you look at its record since the 1950s.” Continental capitalism—practiced in most countries of continental Europe— favors more state control and focuses on wealth redistribution, in contrast to the free market approach practiced in English-speaking countries, such as the US, UK, Australia and Canada.

China’s economic planners, with their perennial concern for avoiding anything that may exacerbate social unrest, such as boom and bust cycles, “might see this European approach as more suitable for China,” Pettis says.

Interest rate liberalization would also weaken the ability of the government to control inflation or inject economic stimulus by raising or lowering the capital reserve ratio at the state-owned banks. It would have a profound effect because of the market share of the state-controlled banks. “The government would be killing one of its tools of economic control,” says Cavey.

Do governments cede this kind of power? It does happen, but the transitions are “difficult and dangerous” according to Cavey, two adjectives that invoke fear in the hearts of China’s rulers.

Yet popular resentment of the banks is leading to tentative moves toward financial reform—for example, the recent pilot program in Wenzhou to legitimize some shadow lending. Informal lenders are encouraged to register as private lending institutions. As an additional example, private citizens now can invest up $3 million overseas without the need for the government to act as a formal middleman. Similar experiments have expanded across China in the past, and if this idea gains traction, the change would be significant. But it would still be far short of interest rate liberalization and the consequent ceding of economic control mechanisms.

Wen may have planted the seeds of a financial services revolution, but it will take more nourishment than the Wenzhou experiment to ensure its growth.