Shifting Trade Flows And The New Consumer

By Dan Keeler

Fast-growing trade between BRIC countries has been fueled by an expanding middle class. Western rivals face stiff local and regional competition in building emerging markets growth.

A decade has passed since the acronym BRIC was first used as shorthand for the emerging powerhouses of Brazil, Russia, India and China. Since then, the four countries have experienced astronomical economic growth. China has proven to be a star among stars—establishing itself as a titan of global manufacturing and growing exports to the West almost exponentially. But while the spotlight has shone on trade volume growth between the BRICs and their customers in the developed markets, another story has been evolving in the shadows.

Over the past decade, trade between the BRICs and North America, Europe and Japan has grown by almost 300% to more than $2 trillion. Over the same time period, trade between the BRIC nations themselves has increased by 1,000% to almost $320 billion, data from the International Trade Center show.

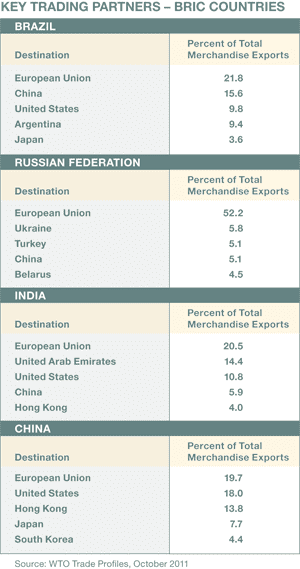

Goldman Sachs’ former chief economist and current head of asset management, Jim O’Neill—who originally coined the term BRICs—notes: “Three of the four [BRIC] countries have a BRIC counterpart as one of their top trading partners.” Implying that the shape of global trade is in the midst of a radical transformation, the dramatic rise in trade volumes that are completely bypassing Western markets will nonetheless have significant consequences for Western and Japanese multinationals.

The growing financial clout—and burgeoning dollar-denominated foreign exchange reserves—of the leading emerging markets are helping to build the case for another major shift in global business: unseating the dollar as the near-universal currency for international trade. Nations such as China and Brazil are making considerable headway in promoting their own currencies’ use in cross-border deals.

Rubens Gama Dias Filho, director of the department for trade promotion at Brazil’s external relations ministry, explains: “In the not-too-distant future we’ll see that the dollar will not be the only currency used in international trade,” he says. “Of course, it is still the strongest and most reliable currency, but I don’t see why we won’t be able to trade in other currencies in the future.” With the steady internationalization of the renminbi, it is likely that this prediction will prove true, further undermining the role the US and its Western brethren will play in the future global economy.

“It used to be that all roads led to Rome—all trade happened through the West and through the US in particular,” says Niraj Dawar, a marketing communications professor at the University 2012 of Western Ontario’s Richard Ivey School of Business. “That centralization is no longer there,” he adds. Indeed, Standard Bank figures show that the BRICs’ share of worldwide trade grew from 7% in 1999 to over 14% in 2008, and trade taking place exclusively between developing countries is growing three times faster than that among developed countries.

Brazil is a case in point. Between 1992 and 2010, exports to Russia grew from $22 million to over $4 billion. Imports from Russia also grew strongly but were still slightly less than half the value of exports last year. Exports to India soared from $200 million in 1990 to almost $3.5 billion in 2010, according to Brazilian government figures.

The pattern is repeated between the other BRIC trading partners, but by far the dominant theme in intra-BRIC trade has long been that between China and every other country. The volume of Brazil’s trade with China, for example, dwarfs that with the other BRICs—and, in fact, now outweighs Brazil’s trade with the US, traditionally its key partner. And this trend is accelerating. Even during 2008 and 2009, when exports from Brazil to other key trading partners were dropping off rapidly, trade between China and Brazil grew strongly, up by over 50% in 2008 and by more than a quarter in 2009. Exports to China in 2011 soared over $40 billion while imports passed $30 billion. China is now the largest single-country export destination—by percentage of total merchandise exports—for Brazilian products, according to WTO figures released in October, 2011.

A recent trip by Brazil’s president Dilma Rousseff to China illustrated the drive to increase trade. In just two days Rousseff and her Chinese counterparts inked a score of trade and investment agreements worth well over $1 billion. Fernando Pimentel, Brazil’s minister for development, industry and foreign trade, noted that there were some hefty Chinese commitments to invest in Brazilian industrial projects, including $300 million for a soybean processing plant in Bahia and another $300 million to help construct a technology equipment plant in Goiás.

India is also keen to ramp up its trade with China. Although China is by far the biggest destination for Indian exports already, the two countries are keen to grow bilateral trade substantially, with a target of $100 billion by 2015.

|

|

Dawar, University of Western Ontario: Brazil-India and Russia-India trade are developing and taking on a new flavor |

China is also by far the most significant BRIC trading partner for Russia. Not surprisingly, given Russia’s abundant natural resources, one of the key elements of that trade is energy. At the turn of the year, for example, the two countries began testing a 750 MW cross-border electricity supply line that will contribute to Russia’s stated goal of supplying up to 60 billion kWh per year to China by 2020. At the same time, the two countries marked the first-year anniversary of an oil pipeline that has already carried 15 million tonnes of oil from Russia into China.

Seth Zalkin, managing partner and co-founder of investment adviser Astor Group, says that China is unquestionably the key player among the BRICs in terms of both trade and investment. “We get calls all the time from Chinese companies looking to open up mines, or to buy agricultural land or agrarian business—looking for inputs for their economy,” he notes. However, Zalkin also sees a considerable level of business between India and Brazil. “One of the areas India has been particularly active in is the pharmaceuticals sector,” he says.

Dawar adds: “China is the big engine driving a lot of this, but we are seeing Brazil-India trade developing, which was quite unexpected. The Russia-India trade is also growing and taking on a new flavor as the other BRICs wake up to the possibilities of inter-BRIC trade.”

A NEW BUSINESS MODEL

The headline trade numbers may be the factor that will keep Western policymakers awake at night, but it is the underlying theme that will most concern US, European and Japanese multinational companies that are keen to expand into the emerging markets. Those companies’ business models have been built on a simple premise: Source products cheaply from the emerging markets and sell them with high margins to relatively wealthy customers in the developed markets. It isa model that has worked spectacularly well for decades, says Dawar. “The margins extracted from the trades were sufficient to pay for very large overheads for marketing and design and R&D and very large headquarters operations in the developed markets,” he explains. “But when your fastest-growing market is in the emerging markets, and your fastest-growing consumer base is the middle class in China, India, Brazil and other emerging markets, you realize that the companies you’re competing with are companies from the other BRICs that have a long history of being able to make low-overhead products and sell them to consumers with limited means,” he adds.

Dawar says many companies have belatedly recognized the threat to their long-term business from emerging markets companies and have also been slow to spot the opportunity that consumers in the emerging markets represent. Having made the mistake of trying to find consumers in the emerging markets that fit their products, rather than trying to make products that fit the consumers, they’re now struggling to make up the lost ground. The key, Dawar says, is to look at the new markets not as incremental spillover business from companies’ traditional home markets but as an entirely new market that requires a new business model. “Once you start to look at it like that, you realize that volume will drive the business model,” he asserts. “You have to make sure your costs of production and branding and research are amortized over very large volumes.”

“Three of the four [BRIC] countries have a BRIC counterpart as one of their top trading partners”

– Jim O’Neill, Goldman Sachs

The competition will be intense. Not only are established multinationals in a race against their peers to establish a foothold in the vast new markets of the BRIC middle classes, they are also facing companies arriving from other emerging markets. Those companies have an inherent advantage over their Western rivals in that they are already familiar with growing their businesses in a high-growth, low-margin environment that is often hampered by political or infrastructural challenges.

|

|

Zalkin, Astor Group: India is very active in the pharmaceuticals sector |

They are also likely to have substantial backing from their governments. Brazil, for example, is heavily promoting the internationalization of its companies. “There is a consensus in government today that strong companies must have an international presence,” says Gama. “They must take advantage of different markets and sources of raw material and labor in other countries.” In turn, they are squeezing out other less nimble or less adventurous rivals.

With their rapidly growing economic might, increasing awareness of—and willingness to use—their political heft, and the burgeoning sense that the emerging world could eclipse developed markets in the coming decades, the BRICs are reshaping the global economy. They are, however, far from a cohesive bloc and, as has become clear in the past six months, they are facing their own challenges in maintaining rapid economic expansion. Although inter-BRIC trade is growing strongly, all four nations remain heavily reliant on trade with the West and Japan. The day when Brazil, Russia, China and India will have shouldered their way past the developed markets and claimed global economic dominance is still a way off yet. But, as Dawar notes: “If current trends continue, by the end of [this] decade inter-BRIC trade may begin to rival BRIC-to-developed-economy trade in absolute size.”

External Reference: