Regional Report: Africa

East Africa is a hotbed of new oil and natural gas finds. Most countries are taking a slow and measured approach to developing their resource boon, but will they avoid the resource curse that plagued many early-developers?

Late in March, after a frenzy of political horse-trading, lawmakers in Liberia signed a deal allowing oil firms Exxon-Mobil and Canadian Overseas Petroleum to develop a potentially rich oil field off the coast of the poor West African nation. Hailed by its supporters as a giant step toward a more prosperous future for Liberia, the deal was also controversial, with critics claiming it short-changed Liberians by giving the country too small a share of potential revenues.

If the two oil companies do strike significant reserves, Liberia will join a growing throng of African countries that have suddenly found themselves as key players in the oil and gas business. Over the past two years a slew of sub-Saharan African countries, including Uganda, Tanzania, Sierra Leone, Mozambique and Kenya, have had meaningful finds. And, according to the US Geological Service, new oil and gas finds will continue. “The USGS estimate of the undiscovered resource potential of sub-Saharan Africa now rivals that of the Middle East and North Africa, North America and South America,” says RFC Ambrian, a mining and energy advisory firm, in a recent report.

Natural gas could be the real game-changer for Africa. In January last year, Africa’s share of proven reserves of natural gas was around 495 trillion cubic feet (tcf)—roughly 7.5% of the global total. Nigeria with 178 tcf, Algeria with 157 tcf, and Egypt and Libya with a combined 128 tcf accounted for the lion’s share of the reserves proven at the start of 2012. By the end of the year, however, the picture had changed dramatically, with new fields in East Africa emerging as potentially dominant.

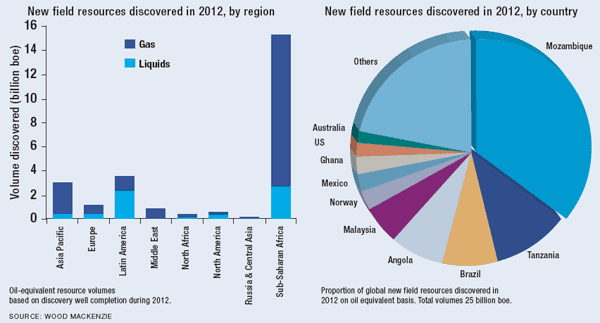

East Africa’s new gas discoveries are simply huge, in both absolute and relative terms. According to energy and mining consultancy Wood Mackenzie, Mozambique, Tanzania and Angola, combined, contributed more than half of the new oil and gas resources discovered worldwide in 2012.

The numbers just keep rising, too. As Global Finance was going to press, Mozambique announced another new discovery that set its total estimated reserves at 150 tcf, a figure that puts it on a par with Algeria, which has the 10th-largest gas reserves in the world.

FUELING PROGRESS

Caglar Somek, partner and portfolio manager of New York frontier markets investment firm Caravel Management, echoes the hopes of many who believe the newly discovered natural resources will help power what is already proving to be a profound resurgence in sub-Saharan Africa’s key economies: “If the resource wealth is prudently managed, it has the potential to create economic engines in countries and regions that have a history of underinvestment and macroeconomic fragility,” he says. “Hopefully, it will also facilitate greater regional integration.”

“If we do find [significant] reserves [in Namibia] … port facilities, airport facilities and communications will need to be upgraded.”

– Wagner Peres, HRT

The potential benefits to such countries as Tanzania, Namibia and Mozambique from tapping their vast oil and gas reserves are far-reaching. By reducing their dependence on imported oil, for example, many of these countries can improve their balance of payments and build foreign currency reserves, enhancing economic stability. They could also use a portion of the production for domestic power generation. With electricity penetration in many of these countries at less than 20%, increasing electricity availability and reliability could have a profound impact on economic performance.

Consultancy Ernst & Young says Africa’s growing natural gas production capability offers “tremendous opportunity for Africa, and it can be a strong ‘prime mover’ for broader economic and social development.” Historically, however, the vast wealth created by the oil and gas industry in sub-Saharan Africa has not had a universally positive impact. There is a tendency for the money generated to end up in a few hands, or to vanish without a trace, and for the rest of the country to see no benefit from the windfall at all. In the worst instances, the flood of new wealth has led to conflict, corruption and chaos—the so-called resource curse.

With decades of bitter experience behind them, many of the continent’s leaders are clearly determined to make sure the money that flows in will be used to fuel long-term, sustainable economic growth that benefits the whole society rather than just an elite few. Namibia, for example, insists that any investment in its fledgling offshore oil sector include a social component that will help the country improve its education system and develop sectors beyond energy.

Equatorial Guinea, whose hydrocarbon production is most likely peaking, is using the income from oil sales to promote a general expansion of its economy. In a late-March commentary on the country’s government policy, the IMF commended Equatorial Guinea’s efforts to broaden its economic base, noting: “Over the last five years, a burst in public investment…largely financed by hydrocarbon revenue, has upgraded transport and power infrastructure and established several national prestige facilities. The resulting stimulus to construction is estimated to have helped raise average growth rates in the non-hydrocarbon sector to about 15%.”

Ghana, considered by many to be a good role model for its management of its newfound oil wealth, is making similar efforts. While the results may be far from perfect, at least the country is working to ensure that its oil bonanza will “support long-term, non-oil-based economic growth and create productive employment for Ghana’s growing young population,” notes one analyst.

Somek is hopeful. “When you speak to policymakers in countries like Uganda, Kenya, Ghana and Tanzania, they appear committed to avoiding the resource curse that has devastated countries like Nigeria,” he comments. “The goal is to use oil proceeds to invest in infrastructure and further diversify the economies.”

Roger Carvalho, CEO, corporate finance, at French oil and gas consultant SPTEC Advisory, says Mozambique’s government is also trying to take a measured approach to the fledgling industry. “The government is in no rush,” he comments. “It is diligent, learning a lot, laying careful plans and taking advice from people who have a lot of expertise.”

Somek says it is too early to tell whether these countries will “be able to channel oil revenues into savings and investments—similar to what Chile, Australia and Canada have achieved. However, should we see the kind of mismanagement and corruption in these new oil states that have plagued countries like Nigeria and Angola, the prospects are heightened for increased conflict and reduced stability,” he says.

LAYING THE GROUNDWORK

Dodging the resource curse takes more than just awareness and a desire to build a sustainable, balanced economy. It involves a tremendous amount of preparation and planning. Wagner Peres, CEO of the American arm of Brazilian oil firm HRT, which has just begun drilling exploratory wells off the Namibian coast, says the demands that a new and significant hydrocarbon discovery can impose on a country are substantial. HRT is expecting to find more than 5 billion barrels of recoverable oil and, “if we do find [significant] reserves, we will need to bring in heavy equipment … Port facilities, airport facilities and communications will need to be upgraded, as they will probably be overloaded very quickly with the arrival of a significant number of people,” he cautions. “The government will need to be very well prepared for the immigrants that will flock there because of the boom of the economy. Being able to handle that will take a tremendous investment and a huge amount of activity in a short time frame.”

|

|

Somek, Caravel Management: If resource wealth is prudently managed, it has the potential to create economic engines in countries that have a history of underinvestment and macroeconomic fragility |

But, argues Carvalho, infrastructure is just one of many challenges that include training decision-makers and a labor force, improving education and ensuring sustainability and environmental protection. Many of these challenges, though, create a catch-22 for a developing country: The country needs to develop its people and infrastructure in order to ensure sustainable and fair exploitation of natural resources, but it needs the revenues from selling those resources to pay for that development.

The answer, in most cases, has been to seek outside investment, much of which will come from the developing world. China and Brazil are already investing heavily in African infrastructure, and while the bulk of the input has been focused on enabling the extraction of raw materials, such as minerals and lumber, the range of projects receiving funding is steadily broadening.

Another challenge, highlighted by the January attack on an Algerian gas production facility by Islamist rebels, is security. In most countries the threat of attacks on oil facilities is a manageable risk, but in countries such as the Central African Republic it is preventing any meaningful exploration from taking place. Pan-African bank Ecobank says CAR is considered a “potentially strong exploration play as its oil reserves straddle its borders with Chad, which is a major oil producer.” While attacks are still taking place, however—the most recent in January—what are likely to be substantial oil and gas reserves will remain undiscovered.

Unlike in prior decades, though, the conflicts in CAR and other potential oil producers in sub-Saharan Africa are the exception rather than the norm. There are fewer active conflicts in Africa now than there have been for decades, and, combined with vastly improved drilling and exploration technology, the spread of peace and stability is proving a major contributing factor to the development of a sustainable regionwide oil and gas industry. Hopefully, as revenues begin to pour in, they will help transform sub-Saharan Africa’s catch-22 into a virtuous circle of economic and social development.

Mozambique Accounts For A Third Of Global New Field Discoveries in 2012