REVOLUTION

By Laurence Neville

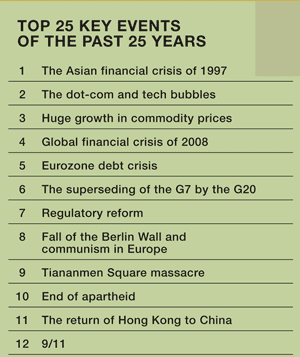

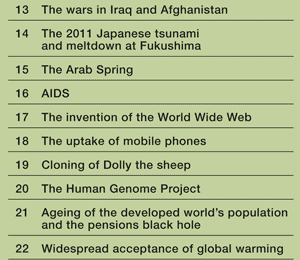

The scale of the crisis that has engulfed much of the world since 2008, which—like a virus—has mutated from a financial sector crisis to an economic crisis to a sovereign debt crisis, is so great that it is easy to forget its antecedents.

|

The quarter of a century since Black Monday in October 1987—when Global Finance launched—has been punctuated by numerous stock market crashes, financial crises and recessions. The savings and loan crisis in the US was followed by the implosion of the Japanese bubble, a banking crisis in Sweden that in many respects presaged the global crisis of 2008, and the dot-com and tech bubble in 2000: when the world suddenly realized that although the Internet may have changed everything, it had not negated the need to have a successful business model.

Among the most important of these crises was the Asian debt crisis of 1997–1998. Although devastating for those countries most affected, especially Indonesia and Thailand, it instilled a prudence that would stand Asia in good stead for the global crisis a decade later: Many countries in the region (most noticeably China) barely noticed it.

Indeed, the resilience demonstrated during the economic and financial crisis of 2008 by many emerging markets dramatically enhanced their role in the global economy. To be sure, China, India, Brazil and other countries were clearly on the rise before 2008, but it was only when the developed world was on its knees that it became clear how important they had become. Consequently, the role of the G20 was elevated and that of the G7 diminished. The ongoing European sovereign debt crisis merely reinforces this trend.

Politically, many of the most important events that occurred over the past quarter of a century seem to belong not just to 25 years ago but to a completely different era. For anyone under 30 the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of communism in Europe belong to a period inextricably linked to World War II and entirely divorced from today’s world. Similarly, the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1994 and the return of Hong Kong to China in 1997—effectively ending the UK’s colonial legacy—seem like bizarre anachronisms from the vantage point of 2012.

Other political events of the past 25 years have greater resonance now. The Tiananmen Square massacre of 1989 is a poignant reminder that economic freedom in China has not been accompanied by any lessening of political control. Similarly, the horrors of 9/11 frame many events that have occurred subsequently. Not just the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan but also the Arab Spring (and the West’s reaction to it) must be understood in the context of a US that is less in step with its allies than in the past and that has lost much of the goodwill from abroad it once could count on.

SCIENTIFIC BREAKTHROUGHS

The past quarter-century has seen medicine contend with new threats, including HIV/AIDS and the rapid spread of new diseases such as bird flu. There have also been genuinely groundbreaking achievements, such as the cloning of Dolly the sheep and the Human Genome Project, which successfully sequenced DNA and has already lead to transformational approaches to medicine. Meanwhile, the invention of the World Wide Web and the widespread uptake of mobile phones have changed the lives of the majority of people on the planet. Who could have imagined that Kenya would one day have one of the world’s leading mobile-phone payment systems?

|

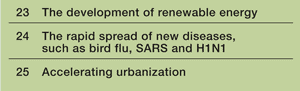

While science has advanced significantly over the past 25 years, attitudes toward it have not always managed to keep pace. The reaction against nuclear power in Japan (and Germany) following the 2011 Japanese tsunami and the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima were understandable. However, other attitudes are less easy to comprehend. While renewable energy has been enthusiastically taken up in many countries, many people—especially in the US—have become more skeptical about the existence of global warming despite ample evidence to the contrary.

Finally, the past 25 years has been one in which the world’s population has become dramatically larger. When Global Finance launched there were a total of 5 billion people alive; the 6 billion mark was reached in 1999 and the 7 billion level this year. As a consequence urbanization is accelerating: By 2008 more than half of the world’s population were living in towns and cities. At the same time, this population is ageing—and not just in developed countries. It remains to be seen how the world will take care of its older citizens in the future.