The drop in oil prices is having varied effects in the Middle East. How countries respond could determine their long-term prospects.

Back To Supplement

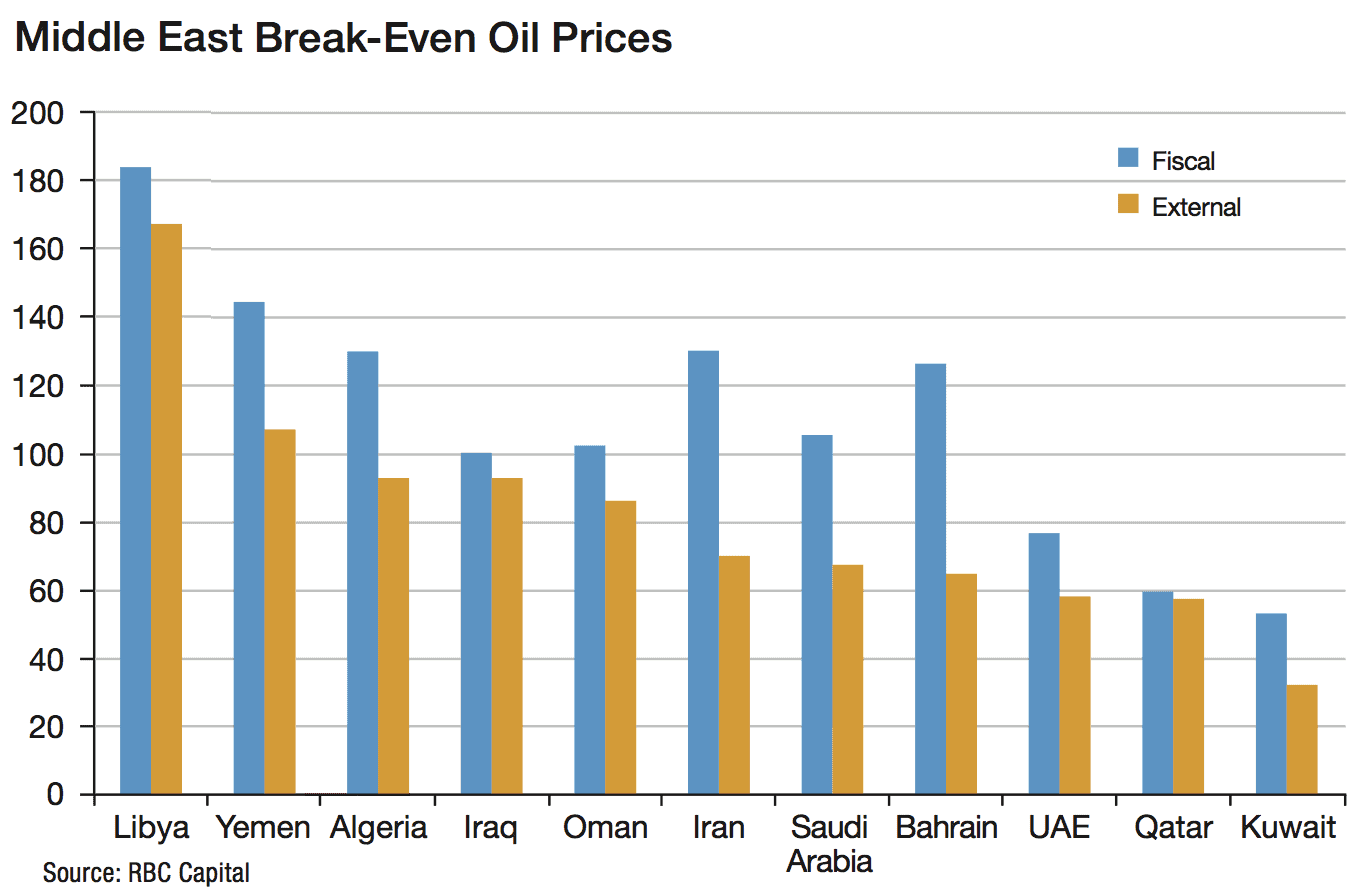

The countries of the Middle East are a diverse group. Topping the list of differences: The countries vary in the required fiscal break-even price of oil per barrel (meaning the price at which the country can balance its budget). According to RBC Capital, using data sourced from the International Monetary Fund via Bloomberg, the break-even price varies from $54 per barrel for Kuwait to $127 per barrel for Bahrain, with Saudi Arabia in between at $106 per barrel. Outside the Gulf states, Libya needs a staggering $184 per barrel.

Thus the effect of falling revenues will vary dramatically. According to Moody’s Investors Service in its 2015 Sovereign Outlook Report and in keeping with the break-even price statistics, Oman and Bahrain are the most vulnerable Gulf states. Kuwait and Qatar are the most resistant to a negative impact.

With few exceptions, banks in the Gulf states take a business-as-usual attitude toward the drop in oil prices. Notwithstanding the importance of the fiscal break-even figures and the possibility of budget shortfalls, the break-even cost of production is much lower than fiscal break-even, according to César González-Bueno, CEO of Kuwait’s Gulf Bank. The price “is relevant for considering the budget, but it’s not relevant from an investment perspective. If you produce oil at one of the cheapest rates in the world, it’s worth investing,” he argues, adding that consumption spending might be more at risk “if the budget was to hit restrictions and deficits …that could affect the private spending.”

Some other risks—such as the age of current rulers—also vary across the region. A ruler’s death can lead to political shake-ups and, with them, changes in business practices. After the death of Saudi Arabia’s king Abdullah bin Abdulaziz in January, his sibling, Salman bin Abdulaziz, took the throne, quickly replacing a number of ministers and dissolving a number of committees supported by his predecessor. Salman is in his seventies and reportedly has health issues, realities that leave open the possibility of another upheaval within the near future. However, Salman has prioritized matters of succession, appointing a crown prince shortly after his accession. Several rulers in the UAE and Oman are advanced in years, whereas Qatar’s ruler, sheikh Tamim bin Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, was reportedly born in 1960.

The political makeup of the Gulf countries presents a risk that cuts across the region, explains Henry Smith, senior consultant at Control Risks, during an interview at the company’s offices in Dubai. “The political economies of all of the monarchies in the Gulf are structured in such a way that the political fortunes of projects and business partners are often tied up in the political fortunes of families and their relationships with the royal family,” he says. This means that companies seeking contracts must choose partners who can help secure and maintain business arrangements.

With those differences and a lingering wariness of the aftermath of the financial crisis as backdrop, Global Finance spoke to Middle Eastern bank CEOs and other Gulf financial executives about the big risks and key opportunities in the region.

BANK PRIORITIES

Taking a leadership role in promoting increased acceptance of renewable forms of energy, such as wind and solar, and creating innovative financing instruments to enable projects in these areas, is a key focus of development for the region’s banks, according to National Bank of Abu Dhabi—and one that NBAD embraces wholeheartedly, says Alex Thursby, group chief executive officer at NBAD. On March 1, the bank released a report entitled “Financing the Future of Energy: The Opportunity for the Gulf’s Financial Services Sector,” which makes a strong case for what it terms a low-carbon future and discusses the expertise required and new financing opportunities.

“We’re starting to develop the expertise, and our role is [mani]fold,” explains Thursby. He defines that role as educating individuals about renewable energy, developing a capability to advise clients initially in the debt and debt-structuring side about distinguishing between viable and non-viable projects and making short-term financial instruments such as trade finance and price hedging available. Ahead of that, however, it is critical, Thursby says, to educate regulators and policymakers about the advantages of renewable energy. “This is what the banks have to do over the period of the next five or ten years,” he says. “We believe right now that our focus is very much on debt structuring and advising on the appropriate financial models.”

At the International Bank of Qatar, there is an emphasis on infrastructure development. Jabra Ghandour, the bank’s managing director, says that he sees reassurance in the Qatar government’s commitment to continuing infrastructure plans.

SEEKING GROWTH

Growth plans vary between banks as to strategy and reasons. Al Ahli Bank CEO Michel Accad views his mandate as redefining the bank’s risk appetite. “It doesn’t mean that you want to necessarily take more risk in everything that you do, but it means that there are certain areas where you would decide you… will accept more risks,” he says. These areas include the contracting sector. “If you manage it carefully, you can grow,” he says, adding that targets include increased work with medium-size businesses.

Growth at Gulf Bank means putting aside its past crisis, according to González-Bueno. In 2009, Gulf Bank narrowly escaped bankruptcy. But it has moved steadily ahead and posted operating profit before provisions of 106.8 million Kuwaiti dinars ($342 million) in 2014. It recorded a net profit of 35.5 million Kuwaiti dinars. That’s a 10% increase over 2013.

Now, González-Bueno says: “We have very specific plans about growth. We are in the process of implementing them and finalizing.” He did not reveal specifics.

UAE countries have enjoyed a unique cachet as a safe haven for people and money for over a decade. The reputation reminds one of the safe-haven status of Hong Kong before China assumed control of the former British colony in 1997. “You could make that parallel,” says Montasser Khelifi, senior manager, global markets, at Quantum Investment Bank, during an interview in Dubai. The reputation is strongest in Dubai, given its well-developed infrastructure and sound legal framework, but the reputation generally applies across the emirates and means that capital and people from other, more troubled areas of the Middle East gravitate toward it.

Moreover, if negotiations between Western powers and Iran conclude successfully, Dubai would reap financial benefits, owing in part to its historic relationship with Iran, according to Smith at Control Risks. “Should Iran emerge from these nuclear negotiations with sanctions relief, then Dubai will be positioned to continue to play a role for Western businesses which [want] to go back to Iran.”

Expansion of retail wealth management product rosters figures prominently in growth plans for banks across the region. QNB Asset Management, a unit of Qatar Group, has 17.4 billion Qatari rials ($4.8 billion) in assets under management, offers funds in equities, fixed income and commodities and has plans to expand its fund universe. Al Ahli Bank takes a different approach. The bank does not plan to expand its proprietary fund offerings from its current two funds. Instead, it aims to grow its fund business by building a platform enabling it to offer third-party funds from other financial institutions.

AFRICAN EXPANSION

Growth can also mean increased activities in Africa. Capital flows from the Gulf to Africa fall into four categories, according to Zin Bekkali, CEO of Silk Invest. During an interview in Dubai, he listed them as portfolio flows, remittances and foreign direct investment, as well as a trickle of aid from Europe. “The big majority of established Gulf companies today definitely have their sights on Africa,” Bekkali says. “We are talking about a region today which has about 800 million people above the poverty line. This number will grow by at least 500 million in the coming ten years.” He says that although no figure specifically for the Gulf appears available, dollar flows from FDI and remittances from across the Middle East to Africa amount to between $50 billion and $60 billion annually for each category.

Qatar National Bank is probably the most aggressive bank in enacting its African expansion plans. As well as the usual means of communicating its ambitions, the company paints the phrase “Our vision—to become a Middle East and Africa Icon by 2017” on elevator doors at its corporate offices in Doha. QNB sees its 20% stake in Togo-based Ecobank as a conduit to 36 countries. “Our [goal with the] Ecobank investment is basically to have a platform in Africa,” explains QNB group CEO Ali Ahmed Al-Kuwari.