Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds are notoriously secretive in terms of their investments and strategy. So what will they do in response to the oil price drop?

Back To Supplement

When it comes to the investing powerhouses that make up Middle Eastern sovereign wealth funds, the key topic that pundits are discussing at the moment is whether, and how, the drop in oil prices could affect the portfolios of the region’s SWFs, and whether the region’s governments will need to, or choose to, make use of SWF assets to finance budget shortfalls should the low price continue indefinitely. But the answer to those questions remains as much a mystery as the investment strategy of the funds themselves.

The price change happened so suddenly and cut so deeply that SWF fund managers have not yet announced any changes in investment direction. “It’s definitely too soon to tell,” says a Dubai-based executive familiar with the UAE’s SWFs. “They haven’t put out anything official one way or the other,” he says. It can be expected that some will elect to ride out the storm, since rock-bottom oil prices, while pleasing to the Western consumer, will not last indefinitely. Alisa Strobel, an economist at consultancy and research firm IHS, estimates that a tightened supply-and-demand balance will generate some recovery in prices, and therefore revenues, in 2016 and that the recovery will continue into 2017.

Moreover, Strobel suggests that in at least some cases, non-oil activity, such as construction in the years preceding Expo 2020 in Dubai, will contribute to a rebound in GDP and government revenues, perhaps lowering the pressure on SWFs.

The drop could drive changes in either of two directions, depending on the outlook and investment philosophy of the fund. It could lead to more conservative investing, with or without greater geographic diversification. Alternatively, it could lead to government demands that an SWF achieve higher rates of return. “To get higher returns, they have to take more risks,” Atif Kubursi, economics professor emeritus at McMaster University in Canada, says. “I would not be surprised if what we’re talking about is happening now.”

The extent to which the drop in oil prices results in a government’s need make up a shortfall from its SWF will vary between countries. It flows from a combination of the actual price per barrel, the fiscal break-even price per barrel, (the price at which an exporting country can balance its budget) and the country’s budgetary requirements and ability to make cuts where necessary.

IHS Economics and Country Risk projects that in Kuwait, lower oil prices will lead to some consolidation of current expenditure, according to Strobel. She explains that the Kuwaiti authorities have used expansionary fiscal policy since 2010 amid high oil prices, and that oil currently accounts for 94% of exports and fiscal revenue, rendering the country vulnerable to a downturn in oil prices. Strobel points out, however, that Kuwait has an enormous fiscal buffer of accumulated surpluses in the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) that will help to smooth consumption for a period of time.

By comparison, Bahrain has little oil, and political unrest and instability in the country have partially thwarted development possibilities, Kubursi says.

Meanwhile a continued drop in oil prices has at least two potential implications, one of them obviously a reduction in cash inflows. Less easily calculable from outside the region is the demands to be placed on SWFs by the region’s governments to make up the shortfall. That calculation will vary from country to country, given the difference in fiscal break-even prices between countries and the ability of individual government to make budget cuts

“One of the questions that has been raised is why Saudi Arabia would reduce the oil prices: [because] they have a Sovereign Wealth Fund they can rely upon,” Kubursi says, adding that Saudi Arabia could ride out a drop in oil prices longer than other countries. According to RBC Capital, the break-even price varies from $54 per barrel for Kuwait to $127 for Bahrain, with Saudi Arabia in between at $106 per barrel.

INVESTMENT STRATEGY

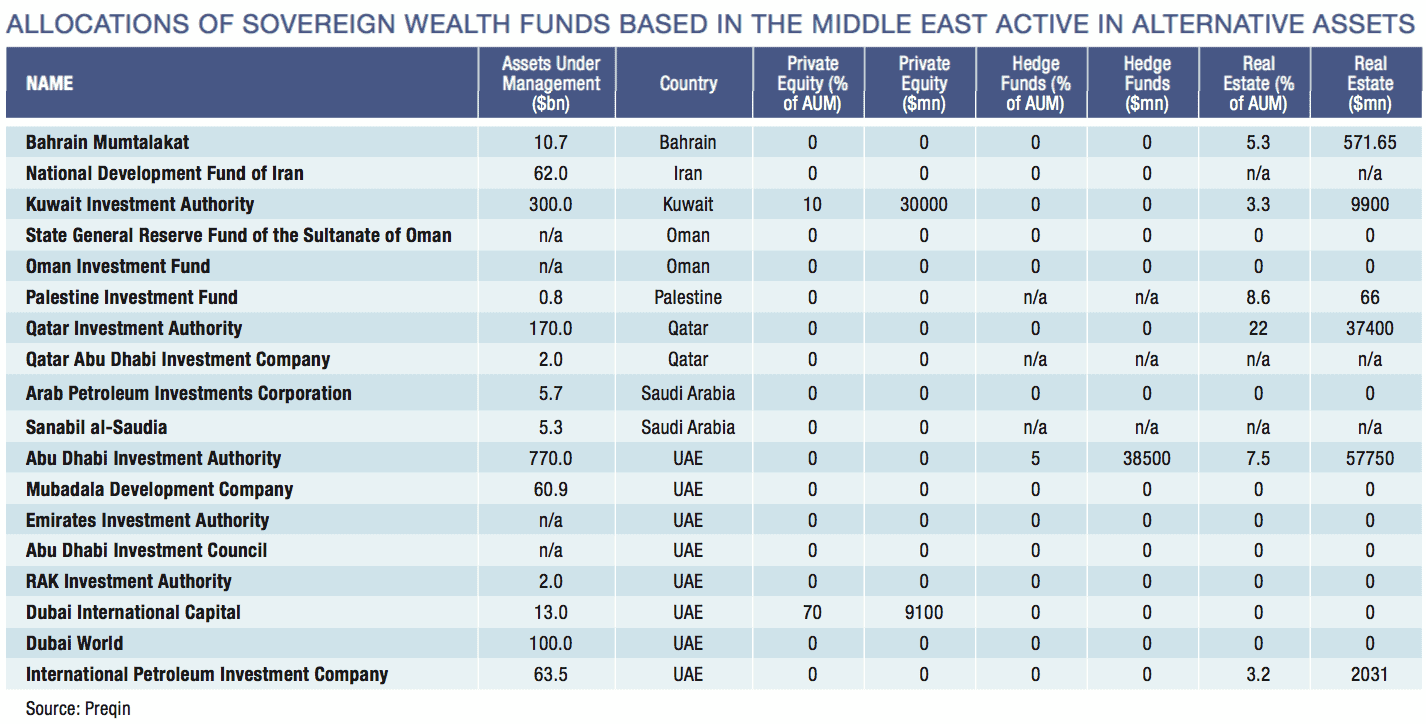

Currently, domestic investment priorities for the SWFs include oil and gas upstream and downstream facilities, energy and power facilities, according to the Dubai-based executive. International priorities include agriculture (particularly in Canada) and water projects. Gulf SWFs exhibit a limited interest in private equity, near-zero interest in hedge funds and a varying interest in real estate. (See chart, below)

Several factors over and above conventional considerations underpin SWF’s investment strategies. The Qatar Investment Authority’s investments in financial services—such as its 50% stake in the Qatar National Bank—appears to reflect the government’s goal to make Qatar a dominant regional financial hub. The Abu Dhabi Investment Authority invests globally, except for Greenland, Iceland, parts of Central and South America and Africa. Although that appears aggressive, it has roughly 55% of assets in index-replicating strategies, a conservative tactic.

Fear of the “Dutch disease” provides other clues to the SWFs’ investment philosophy, particularly international diversification, says Kubursi at McMaster University. In the 1960s the Dutch saw a sudden rise in state wealth owing to exploitation of gas deposits in the North Sea, which they mostly invested at home. This led to a sharp rise in the value of the Dutch guilder, and hurt exports. “They [Gulf SWFs] learned from the Netherlands,” he says. “You might as well use the money [for] investing abroad—which reduces inflationary pressures at home.”

NO NEED FOR TRANSPARENCY

In Gulf region SWFs, the government is the only shareholder, and the amount of information released reflects a specific government’s willingness to divulge it.

They vary in rankings on the Linaburg-Maduell Transparency Index, published by the Sovereign Funds Institute. The index grades funds based on criteria such as clarity of statistics and strategies and availability of audited reports. For the fourth quarter of 2014, the Bahrain Mumtalakat Holding Company scored 10/10, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority tallied 7/10, and the KIA received 6/10. The Qatar Investment Authority made 5/10 and the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, long considered one of the least transparent SWF’s, scored 4/10.