The Middle East is no stranger to political and economic uncertainty, but simmering religious and political tensions and stubbornly low oil prices have dealt the region a difficult hand. The question now is: How will countries play in order to win?

Back To Supplement

Sectarian tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran, as well as between Shiite and Sunni Muslims, and an intractable conflict in Syria have pushed the Middle East to the brink. For years Riyadh and Tehran confined their mutual loathing to histrionics along with camouflaged support for opposing proxy militias. That changed in January when Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic relations with Iran after protesters—enraged at the execution of sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, a prominent Saudi Shiite cleric—torched the Saudi embassy in Tehran and held similar protests at the Saudi consulate in Mashhad.

Although not new, the Persian-Arab standoff is unfolding at a time of unprecedented regional economic upheaval. Amid the uncertainty, the Gulf’s heavy reliance on hydrocarbon revenues could presage a reshaping of the regional political map. “The ongoing rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia has a profound impact on the Gulf and the Middle East more broadly,” says Torbjorn Soltvedt, head of Middle East/ North Africa at risk consultancy Verisk Maplecroft.

When sanctions against Iran were lifted in January, president Hassan Rouhani wasted no time in marking Tehran’s return to the global economy. On state visits to Italy and France, Rouhani signed 14 economic and cooperation agreements as well as a massive $25 billion order with Airbus for 118 aircraft. The visits were not just about economics; they provided the Islamic Republic with a long-denied public relations platform in the intensifying battle for ideological supremacy in the Middle East.

Oil Prices Weigh Heavily

Following a slide of more than 70% slide in oil prices from mid-2014, Gulf economies are reeling from the impact of declining fiscal incomes. Yet austerity is not a word policymakers or their citizens are used to. Saudi Arabia, the Gulf’s largest economy, racked up a deficit of $98 billion in 2015, close to 15% of GDP—its largest ever. The kingdom has vowed to implement widespread economic reforms in a bid to reduce its huge dependency on oil, which accounts for as much as 90% of government revenues. The question is whether Riyadh’s newfound dynamism is too little, too late.

In January, Standard Chartered stated that speculative forces could drive oil prices much lower before the market capitulates. “We think prices could fall as low as $10 a barrel before most of the money managers in the market concede that matters have gone too far,” it states. According to Bank of America Merrill Lynch, an extended period of low oil prices could mark the peak of the Gulf macro story. That finding was echoed by the International Monetary Fund, which slashed Saudi Arabia’s growth rate this year to just 1.2%.

The convergence of significantly reduced government incomes and a fluid political backdrop has conjured a perfect storm for Gulf leaders. Publicly at least, solidarity among the six-member Gulf Cooperation Council bloc is essential to counterbalance an increasingly assertive Iran, but there are varying interpretations of how the GCC should deal with Tehran. Saudi Arabia and Bahrain are the most hawkish, viewing Iran as an existential threat. The United Arab Emirates has a more measured view, as Dubai in particular—which is home to some 500,000 Iranians—stands to gain from Iran’s reintegration into the global economy. Oman, whose policy is neutrality, is also considered an early beneficiary from the easing of sanctions. Kuwait has a sizable Shiite population, but supported Saudi Arabia by withdrawing its ambassador to Tehran. Qatar’s policy is less clear. In the past it has clashed several times with Saudi Arabia’s leadership, and it has shared energy interests with Iran in the South Pars/ North Dome gas field in the Persian Gulf.

The slump in oil prices has benefited other Middle Eastern countries, notably Lebanon and Jordan, which saw their fiscal positions improve, pushing inflation into negative territory. Yet economic gains are overshadowed by proximate conflicts. Egypt’s economy continues to struggle with fears of further terrorist attacks—fears that undermine tourism and deny essential foreign exchange. Devaluation of the Egyptian pound looks increasingly probable.

Shoring Up Stability

Lavish handouts and well-paid government jobs for GCC citizens could soon be history as Gulf countries grapple with fundamental decisions over the direction of their respective economies. Whether citizens accept a diminution of the social compact that provides a cradle-to-grave safety net will undoubtedly affect the pace of reforms. Saudi Arabia will be a litmus test—it raised some gasoline prices by 66% and slashed subsidies on gas, diesel, kerosene, electricity and water. Analysts say it is too early to assess what impact the reforms have had on popular sentiment. What is clear is that the longer oil prices remain low, the greater the hardship will be on the Gulf’s population. Still, there is some good news. Bank of America Merrill Lynch believes more-prudent spending by GCC governments will lead to a fall in the break-even price—the price required to balance fiscal budgets—of a barrel of oil.

There is a caveat, however. Only some Gulf states, like the UAE, have made significant progress at economic diversification and, as a result, are better placed to weather the downturn. Despite diversification there is the visible slowing of the non-oil economy in the UAE. The Purchasing Managers’ Index, which covers the entire non-oil private sector, fell from 54.5 in November to 53.3 in December—the lowest reading in more than three years, according to Capital Economics.

The expectation that the Gulf economies will have to draw increasingly on reserves is putting pressure on GCC currency pegs, as five of the six countries are pegged to the US dollar; only Kuwait links its currency to a basket. There is intense speculation that Saudi Arabia could be forced to devalue. Although devaluation is a “black swan” event, the unpredictability of affairs in the Middle East is alarming investors. Forward contracts on the Saudi riyal spiked in January, implying that the market expects devaluation. However, Oman and Bahrain look the most exposed to devaluation—both face spiralling deficits and limited reserves with which to defend their currencies. Nevertheless, Societe Generale says the chances of a devaluation of the Saudi riyal have increased. In a report the bank assigned a 25% probability to a near-term (less than six months) currency devaluation change, increasing to 40% if oil stays at current levels throughout 2016, rising to 60% if oil stays sub-$50 per barrel for the next two years.

The tightening economic environment is also fueling concerns over credit quality. Credit default swaps on Saudi Arabian debt have ballooned, and Dubai’s debt pile, estimated to have reached $130 billion at the end of 2015 by the Institute of International Finance, is once again garnering the attention of distressed debt investors. In February, Standard & Poor’s cut its foreign- and local-currency sovereign credit ratings on Saudi Arabia by two notches to A-/A-2 from A+/A-1. It was Saudi Arabia’s second downgrade since October.

We think [oil] prices could fall as low as $10 a barrel before most of the money managers in the market concede matters have gone too far.

~ Standard Chartered

In contrast, Iran’s economy may be resilient enough to withstand a protracted period of low oil prices. According to Moody’s Investors Service, structural reforms have strengthened Iran’s fiscal foundation. The force of sanctions meant the Islamic Republic had to adapt to the reality of lower oil prices much earlier than other oil exporters. “Sanctions relief will grant Iran access to an estimated $150 billion in frozen foreign assets—we project the implementation of investment plans, as well as a recovery in oil production, to contribute to higher GDP growth of 5% in 2016–2017,” says Atsi Sheth, an associate managing director for sovereign ratings at Moody’s.

If, as expected, Gulf economies decide to tap global bond markets to finance deficits, they may come under further pressure to liberalize their economies. In a marked policy shift, Riyadh is widely expected to seek its first-ever foreign bond issue this year. The recent credit downgrades will be a crucial test of banks’ appetite for risk and sentiment toward Saudi Arabia, analysts say.

A New Operating Environment

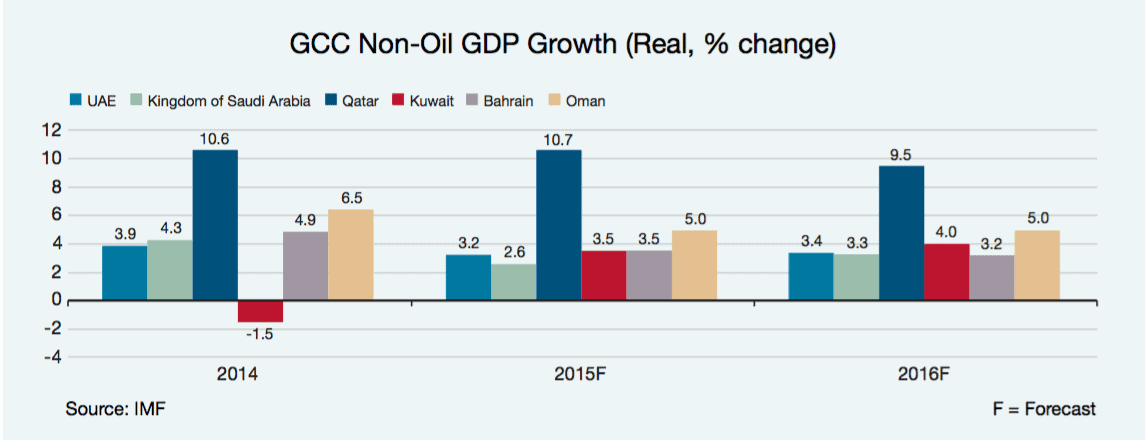

Strong capital buffers are likely to support banks through 2016 and beyond, but downside risks are evident, Moody’s says. The banking sector in Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and UAE remains strong and stable, owing to large reserves, which the rating agency estimates at $2 trillion. Non-oil GDP growth is slowing but remains positive—large projects, including the 2020 World Expo in Dubai and the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, continue to buoy the banking sector.

Credit growth is forecast to be in the 4% to 10% range this year, as private-sector declines are moderated by new government borrowings from local banks, which will support profitability and margins. However, banks in Bahrain and Oman look vulnerable as a result of higher break-even prices for oil and their limited ability to support the economy without compromising credit-worthiness.

Moody’s predicts asset quality will face mild pressures but stay solid, with nonperforming loans expected to reach a GCC average of between 3% and 4%. Jan Dehn, head of research at emerging markets investment manager Ashmore, believes economic constancy is contingent on how well the GCC adjusts to lower national incomes. “GCC countries have low debt levels and high levels of reserves, which gives them the ability to adjust domestic demand slowly without impeding overall stability.”

The Middle East is not a newcomer to instability, but the polarization of current tensions places it in uncharted territory. Describing the region as a powder keg seems hackneyed, but the description is now more apt than it has been for a long time.