Changing fortunes in the region’s oil-rich economies have made the secretive world of sovereign wealth fund asset allocation even more opaque.

Back To Supplement

How much are Gulf-based sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) unwinding investments and reappraising asset allocation strategies in reaction to the collapse in oil prices? That is the question global money managers are trying to answer as they contemplate a shrinking investment pool and the prospect that the biggest Gulf funds are increasingly managing investments in-house.

In February a routine ratings report from Fitch on the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority provided some insight into the strategy of the Gulf’s largest fund at a time of unprecedented turmoil in energy markets. Fitch said it expects ADIA’s assets to fall from an estimated $502 billion at the end of 2014 to $475 billion at the end of this year. The implication is that the Abu Dhabi government will use the $27 billion shortfall to partially plug a budget deficit forced on the emirate by the dramatic drop in oil prices. At the end of 2015, Abu Dhabi’s budget deficit widened to 13.2% of GDP, up from 7.2% in 2014.

ADIA, the second-largest SWF in the world, according to the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute, symbolizes the shift in strategy by Gulf sovereigns as they bring cash home in a bid to shore up domestic economies.

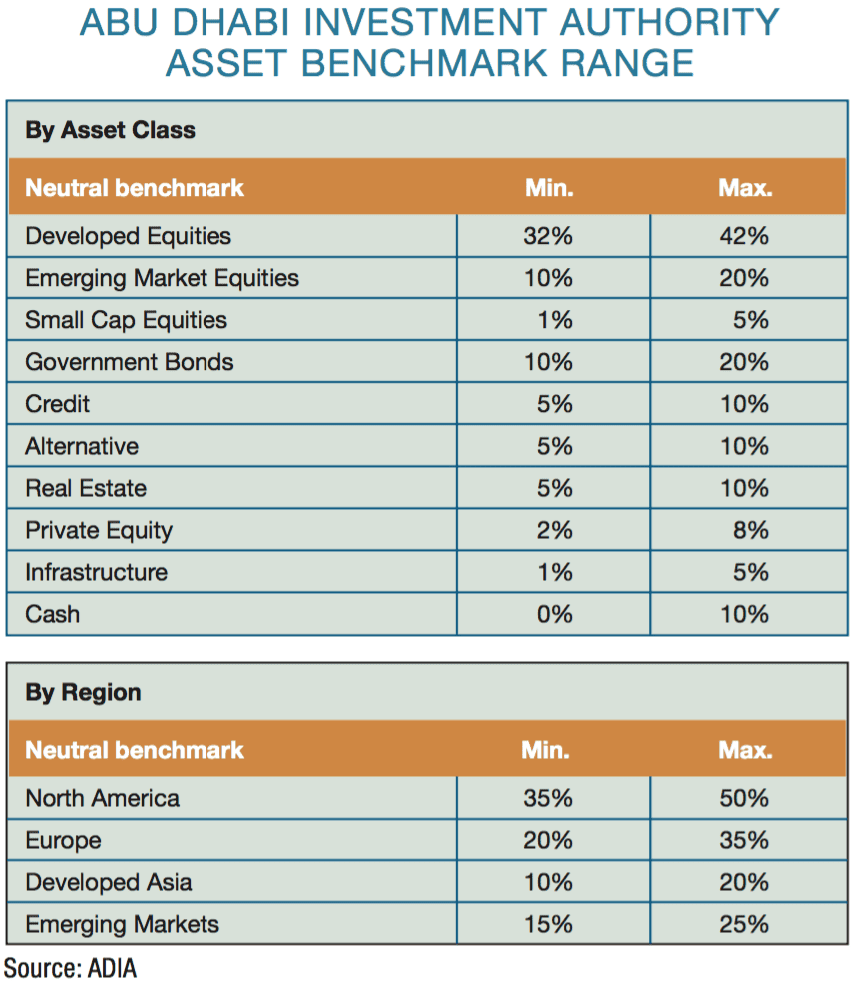

The Gulf funds are notoriously opaque, although to varying degrees. The ADIA does not disclose its exact asset allocation, opting instead for a neutral benchmark range segmented by asset class and geography. However, in its 2014 review ADIA stated that it had increased the flexibility of managers to target alpha.

Historically, ADIA was a major buyer of US institutional real estate. But in the wake of reduced government revenues, all Gulf-based SWFs have been assessing their investment strategies. The Qatar Investment Authority has previously made major allocations to private equity, yet analysts say Gulf funds must balance the need to redeem investments against the backdrop of low valuations in some asset classes. Nonetheless, there is mounting evidence Gulf funds are drawing down reserves at an increasing rate. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, which is also the country’s central bank, says total reserve assets fell to $602 billion in January—a decline of $14 billion from December.

Changes in regional geopolitics are also impacting investment strategy. In January the Oman Investment Fund signed a memorandum of understanding with Iran’s Khodro Industrial Group to study a proposal for a $200 million auto plant in Oman—it is one of the first agreements signed by Iran with a Gulf state. In February the Omani fund also inked an agreement for a 5 million-square-meter medical city in Barka, a clear signal that domestic investments have leaped up the political and economic agenda.

[Sovereign wealth] clients will search for the highest possible returns, which could eventually lead to lower management fees, as money managers will be competing to attract funds.

—Apostolos Bantis, Commerzbank

Confronting A New Reality

A criticism leveled at Gulf SWFs is that they have not invested in renewables, which, analysts claim, could have provided a hedge against the downturn in oil prices. Still, the investment intent of each fund varies; in the case of ADIA, its stated mission is to improve the long-term prosperity of Abu Dhabi and make financial resources available when necessary to maintain the future welfare of the emirate. That is code for supporting government expenditure when there is pressure on revenues, as is the case now. Kuwait has a clear separation between its General Reserve Fund (for macro stabilization) and the Future Generations Fund (for saving) under the umbrella of the Kuwait Investment Authority.

In contrast, Qatar seeks to grow its fund for future generations, and Bahrain’s investment arm, Mumtalakat, says its investment objective is to enhance the value of its portfolio for future generations. That intent may be tilting away from US investments, judging from reports in February that Mumtalakat had pumped $250 million into the Russian Direct Investment Fund. Mumtalakat’s media office in Bahrain did not respond to questions from Global Finance about the investment. On its website, RDIF describes itself as a $10 billion fund established by the Russian government to make equity investments, primarily in the Russian economy.

For all the market speculation about the actions of Gulf funds, it is difficult to establish facts. Apostolos Bantis, a credit analyst at Commerzbank in Dubai, told Global Finance it is unlikely there will be any precipitous change. “Lower oil revenues will at some stage require changes on asset allocations and will result in smaller volumes of investments, but the function of these funds will remain a diversification into international assets.” That may offer a temporary respite to money managers, says Bantis, but the situation could change if oil prices stay low for an extended period. “Such a scenario raises competitive pressure among asset managers, as [sovereign wealth] clients will search for the highest possible returns, which could eventually lead to lower management fees, as money managers will be competing to attract funds.”

Edwin Truman, a nonresident senior fellow at Washington’s Peterson Institute for International Economics, says that by December 2015, SWFs had withdrawn $140 billion from their peak in March of that year, or 1.9%—hardly a rush for the exit. However, the relatively small decline belies an important point, Truman argues: There have been substantial inflows into Gulf SWFs in the past five years. “This means the impact on money managers and markets is that there is less new money to deploy and less support for stocks and bonds and other types of investments. It follows that funds have been doing more in-house management and [have] cut back on mandates to outside managers.” Another fact about the $140 billion outflow that may concern money managers, adds Truman, is that all of the withdrawals came from the oil and gas sector, which make up approximately 55% of all SWFs.

Whether oil prices recover in the second half of 2016 is still open to question, but it is clear that the longer oil prices languish or decline, the more governments in the Gulf are likely to tap reserves. Admittedly, overall levels of borrowing in the Gulf are low, giving governments flexibility to borrow, although prospects for that option have dimmed. In February, Bahrain pulled a planned $750 million bond sale after Standard & Poor’s downgraded the kingdom’s credit rating to junk status. At a time of increasing volatility in global financial markets the ability of Gulf SWFs to surprise cannot be underestimated.