The treaty does not overrule provisions set by numerous and often conflicting authorities that currently regulate fishing, shipping and deep-sea mining on the high seas.

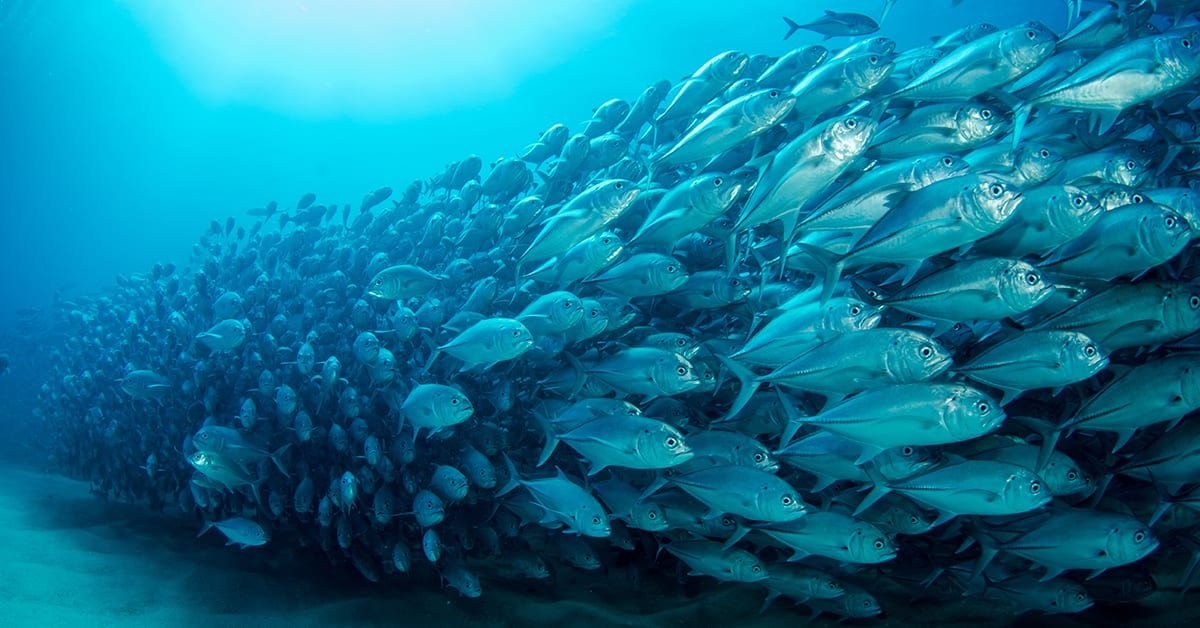

High seas, the vast waters that lie 200 nautical miles beyond national territorial jurisdictions, make up almost two-thirds of the oceans—yet until today, only 1.2% enjoyed protected status. Last month, after two decades of negotiations, nearly 200 countries agreed to a framework aimed to preserve marine life and biodiversity.

“Anytime the world’s governments come together and agree on how to tackle a global challenge such as how to sustain our ocean, it is a cause for celebration,” says Rashid Sumaila, this year’s winner of the Tyler Prize, often referred to as the Nobel award for the environment, and a professor at the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries and the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia. While a tremendous win for ecosystems, local communities and future generations, the agreement—Sumaila and other experts say—falls short in many respects.

Held up until now by disputes over funding and the huge economic interests at stake, the treaty does not overrule provisions set by numerous and often conflicting authorities that currently regulate fishing, shipping and deep-sea mining on the high seas. And the accord will only take legal effect once 60 nation members have ratified it, which could take months or years.

The risk is the continued exploitation of these waters, with devastating effects for marine species and coastal habitats—and for global society as a whole. The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that over three billion people rely on them for their daily protein intake. Further, oceans generate about 50% of the oxygen on the planet and absorb 30% of its carbon dioxide.

Threats to oceans have only intensified in recent years. Mining companies are racing to mine ocean floors for the rare metals needed for electric vehicles and other green technologies; pharmaceutical firms are looking to exploit the genetics of ocean life to develop new drugs; and new shipping corridors are constantly opening—including the currently under development Northern Sea Route, which could soon become the fastest passageway between Asia and Europe.