Who gets it, how much—and when—could make or break economies this year.

As 2020 came to a close and the new year opened up, Covid-19 infection rates went soaring again—in a second wave that included a new, apparently more contagious, strain of the virus.

Nevertheless, at the same time, a wave of optimism washed through world economies as vaccine excitement took hold, especially in the West. In December, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine got emergency approval and the EU, UK, US and Canada opened vaccination campaigns. News of government approvals and successful trials, video of frontline workers and political leaders getting injections, and above all the prospect of returning to business as before, inspired some revisions to growth forecasts. Capital Economics, for example, lifted its estimate for 2021 world GDP to 6.8%.

Yet the positive overall view glosses over some painful details in access, timing, logistics and costs. Immunization rollout won’t be a fair game, with huge variation in access between countries and individuals. Kate Dodson, vice president for global health strategy at the United Nations Foundation, which helps fund the Covid response of the World Health Organization (WHO), explains that WHO guidelines prioritize frontline health workers and essential workers first and allocate to high-risk populations from there. “Healthy, young people will likely be last to receive the vaccine,” she says, “sometime in 2022.”

The next year could see a widening gap in economic productivity between rich nations and poor ones, with potentially severe consequences for those that cannot get the virus under control. That divide itself could levy a costly penalty on our interconnected modern world. “Vaccine nationalism, where countries push to get first access to a supply of vaccine, potentially hoarding key components for vaccine production, could cost the global economy $1.2 trillion a year in terms of GDP,” according to an October study by the Rand Corporation.

Meanwhile, urgent need in many countries gives working Covid-19 vaccines power as commercial and diplomatic tools. And while Western—certainly US—media focuses almost exclusively on the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, there are many others.

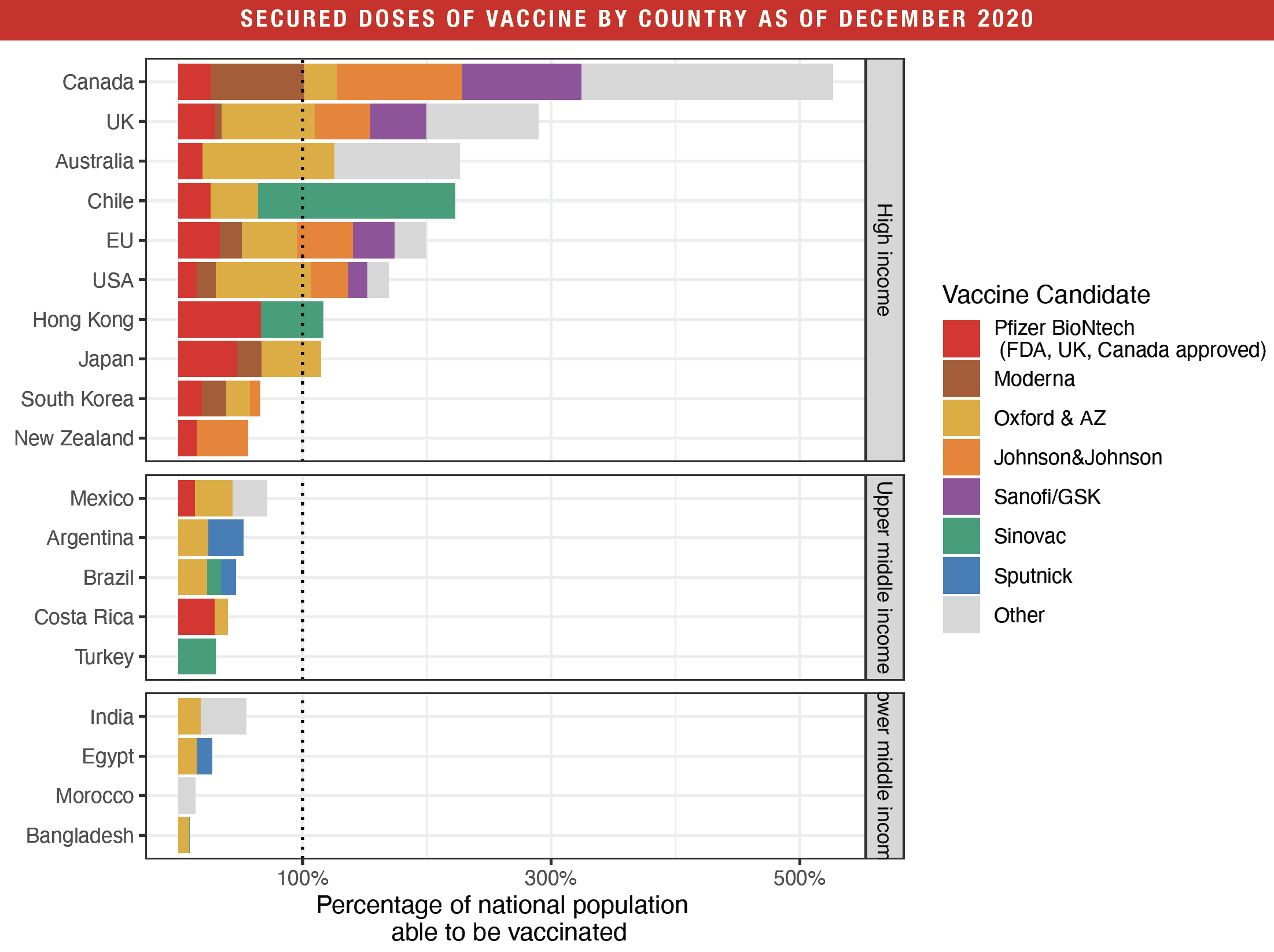

Data on vaccine purchase agreements are often opaque, with most contracts not disclosing the prices and some countries not disclosing much information on production and availability. According to the Duke Global Health Innovation Center (GHIC), among the few collecting this highly sensitive data, Chile will purchase the bulk of its vaccine from China’s Sinovac—which is also supplying Hong Kong, Turkey, Indonesia, Brazil and Bangladesh. A Malaysian company is seeking halal status for vaccine supplies to come from a Chinese firm, for distribution to Muslims. Meanwhile, Egypt and Brazil are among those that have signed on for some of Russia’s Sputnik vaccine.

Who Gets How Much?

From the early months of the pandemic, in the rush of funding for potential vaccines, dozens of pharmaceutical entities entered the fray. No one could predict which would succeed. The vast majority of vaccine candidates fail; and even after successful development, there are challenges in manufacturing and distribution. Consider the Pfizer vaccine’s supercold temperature requirements.

Wealthy governments negotiated purchase agreements, sometimes with multiple drugmakers, spreading their bets. According to the Duke GHIC database, Canada negotiated for enough vaccinations with various makers to inoculate all its people several times over. “High-income countries, which represent 16% of the world population, have more than half of the doses that have been reserved,” says Andrea Taylor, assistant director of programs at the Duke Global Health Institute. “Low-income countries, which represent 9% of the world population, have zero.” In total, only eight countries, plus the EU as a whole and Hong Kong, have procured enough doses to cover the totality of their populations.

The ability to inoculate means resumed business and a return to “normal.” “We see the US coming out first, because they’ve bet very much on Pfizer and Moderna and they have large production facilities,” says Rasmus Bech Hansen, CEO at Airfinity, a science information consultancy with a key database on vaccine availabilities. He believes the US could recover some semblance of normal life as early as May or June 2021.

Recovery will also be powered by the private sector. By November, for example, Ford Motor had ordered a dozen ultracold freezers to store vaccines for its rank-and-file staff. “In the short run this market will be government controlled, simply because there’ll be such a need,” says Hansen. “[But] we will no doubt see a private market for these vaccines.”

China and Russia both have vaccines already in production, being tested and distributed domestically. Vaccines from Sinopharm and Sinovac Biotech have been in late-stage trials in Gulf states including Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which on December 10 became the first government to approve a Chinese vaccine. The UAE’s prime minister and Bahrain’s crown prince, along with a slew of senior officials in both countries, have received the Sinopharm vaccine.

“And then there are places like India,” Hansen says. “It’s a very large country that needs lots of vaccines, and they haven’t procured enough.” Hansen notes that the current darlings from Moderna and Pfizer are unlikely to be distributed in less developed parts of the world for both pricing and logistical reasons. As a result, he adds, those countries “will simply not be able to immunize the population as fast.”

Concerns about inequity in vaccine distribution prompted WHO to launch Covax in partnership with the UN, European Commission and others. Covax is a global partnership designed to support vaccine development and also equitable distribution. Partner nations pledge payments to guarantee access to a certain portion of vetted products. The initiative holds a portfolio of more than 170 candidate vaccines—the vast majority of which will fail. So even Covax is projecting it will take until the end of 2021 to get to two billion doses—enough to protect high-risk and vulnerable people, as well as frontline healthcare workers. It is less than 25% of the world’s current population of nearly nine billion.

“We’re most excited about AstraZeneca and the Johnson & Johnson vaccines in terms of equity,” says Duke’s Taylor. “That’s because they have prioritized low-middle income countries in their distribution and because they’re feasible to roll out in low-middle income countries.”

The global health team at Duke is also watching with close interest the progress of a few vaccine candidates currently under development in India—even though they are at very early stages. Notably, these vaccines are heat-stable, which means they don’t need any refrigeration at all; and one of the most interesting—the result of a partnership between Washington University and India’s Bharat Biotech currently in Phase 1 trials—is administered as a nasal spray. “These would be absolutely game changers for hot climates,” Taylor says.

In the meantime, India has contracted with Oxford/AstraZeneca for its vaccine, as well as with Russia for Sputnik. Others signing on for Sputnik include Argentina, Belarus, Mexico, Uzbekistan and Venezuela. Chinese suppliers have contracts with Turkey, Chile and Gulf nations, among others.

But these vaccines have not yet been approved by WHO, and information on development in those countries is hard to come by. Hansen suspects that Russia may lack the capacity to scale up production of Sputnik. With supplies limited by production capacity and logistics, these pledges may require delayed inoculations for some of their own citizens, hampering the recovery of the domestic economy.

Still, Rand Corporation pegs the cost of supplying the vaccine to lower-income countries at $25 billion; it puts the cost to wealthier countries of not doing so at $119 billion. “For every $1 spent” vaccinating their poorer neighbors, Rand concludes, “high-income countries would get back about $4.80.”

In the coming months, there will be several elements that will help countries that have remained behind to get their doses. For one, there will be international aid. In December for example, the Asian Development Bank launched a $9 billion effort to help low- and middle-income countries with vaccine infrastructure, such as cold-chain storage, surveillance and outreach.

Vaccine Optimism

The goal of vaccination efforts is, of course, to return to “normal” levels of human interaction. “For the world as a whole, there are reasons to think that activity will not quite return to its pre-virus path in the next two years; but it should come close,” Jennifer McKeown, head of the Global Economics Service at Capital Economics, comments in a blog post. Overall, she believes, poorer emerging markets, including Africa and parts of Latin America, will see economic recovery hampered by slow distribution of vaccines; while emerging markets of Europe will benefit from the EU’s procurement process.

Even with multiple successful vaccine products, more difficult months lie ahead. Some nations may struggle to get enough citizens to take vaccination so as to achieve widespread immunity. Indeed, the case of Vietnam, which has been relatively successful in containing the virus and is showing relatively robust economic growth, illustrates the link between social behavior and the virus. On the other side, Japan’s misguided “Go To Travel” program encouraging domestic tourism seems to have sparked a resurgence of infections.

As always, the impact will be hardest on small and medium-size companies (SMEs). “We’ve got this long period of time before things actually recover. A really big worry for us is about the impact of this, particularly on small and medium-size enterprises,” says Oliver Wright, who leads Accenture’s Consumer Goods and Services group. “Most small and medium-size businesses don’t have the cash reserves to navigate a cycle of lockdowns and significant drops in demand.” The US economy lost a net 321,000 SMEs from 2008 to 2010 as a result of the financial crisis, he notes, and “could easily eclipse this number in 2020 alone.” While vaccines hold promise, the pandemic will leave permanent scars.

“I did not live through the Great Depression, but my parents did and they were affected for life,” says James Rickards, author of The New Great Depression: Winners and Losers in a Post Pandemic World. “This will be very similar.” A 2020 study published by the Federal Reserve of San Francisco looked at 650 years of pandemics and found that monetary policy, economic growth and other policies do not normalize for 30 to 40 years. “If 2019 is your base year to define normal,” Rickards says, “well, we’ll never see normal again. Ever.”