In the wake of a deep economic crisis, Portugal is on the road to recovery, a rare example on the eurozone’s periphery.

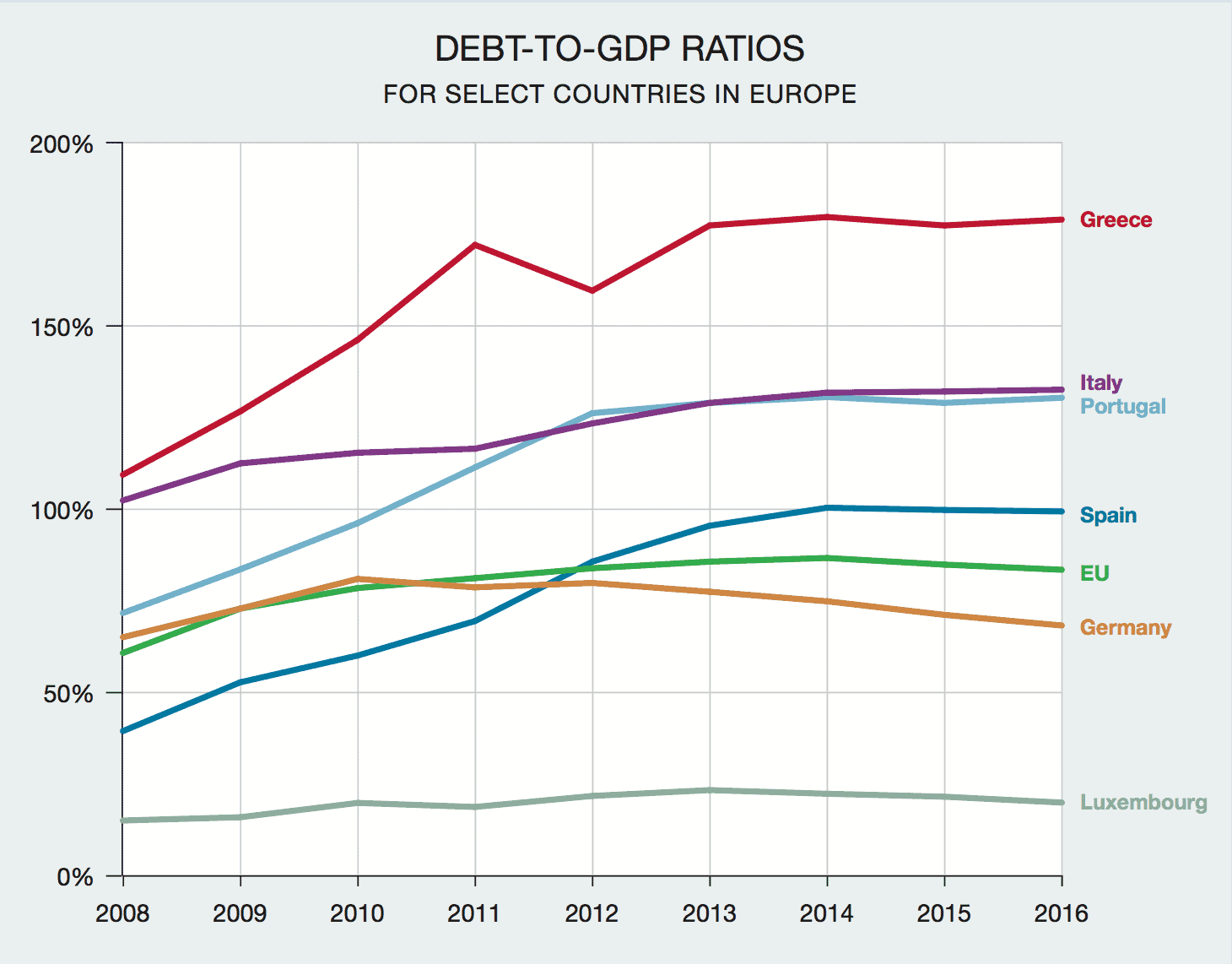

Portugal’s public debt-to-GDP ratio is the third-highest in the EU, following Greece and Italy. This represents a big drag on the economy, because funding is still weighed down by repayment needs.

The three major ratings agencies—Fitch, Standard & Poor’s and Moody’s—have rated Portugal sovereign debt as junk since the crisis. Only DBRS (originally known as the Dominion Bond Rating Service), a Canadian credit agency, left Portugal above investment grade; but that one rating is enough to allow the European Central Bank to keep buying Portuguese debt in its quantitative easing efforts.

Yields on government bonds have fallen drastically in recent years, with 10-year government bond yields at around 3% in 2017, down from 17% in 2012, fostering expectations of an improvement of the country’s credit rating.

“If this kind of economic performance continues—and I don’t see why it should not—it will be tough for credit rating agencies not to review the Portuguese outlook,” says Jose Brandao de Brito at Millennium bcp. “I would expect at least one of the three of them to act before year-end.”

Santander Totta’s Vieira Monteiro points out that Italy, for example, has a debt-to-GDP ratio as high as Portugal’s, yet its debt is rated investment grade.

“Public debt is high, but by itself is not a factor inhibiting a credit rating upgrade,” he says. He adds that given the vast improvement in fiscal discipline, the issue of the high level of debt should find a solution. “[Fiscal discipline], together with stronger GDP growth (both real and nominal), should bring forward a sharper decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio,” he continues. “We would expect the recognition of the underlying improvement of fiscal accounts through an improvement of the credit outlook, or even the rating, in the coming quarters.”

Such expectations aren’t shared by all. Others are less optimistic about the potential for a move by the three major rating agencies. But all agree that a return to investment grade for the Portuguese sovereign debt will represent an important step for the overall economy.

“I believe ratings agencies will be cautious, and we will probably have to wait to see the signs of a credible decline in public debt,” says Novo Banco’s Andrade. “I believe that the agencies may also want to wait for more clarity in some external risks like the election in Italy.” The agencies, he notes, will likely be circumspect about the move, because it isn’t a gradual movement but a discrete crossing of a line from junk to investment grade; and it will have “major implications for the exposure to Portugal of several institutional investors.” It will also, when it comes, have major implications for Portugal “in terms of financing conditions, confidence and growth prospects.”