MOVING FORWARD IN FITS AND STARTS

By Valentina Pasquali

Angola is making all the right moves when it comes to attracting inter-national investment and diversifying its economy beyond oil. However, corruption and bureaucracy still present challenges for investors.

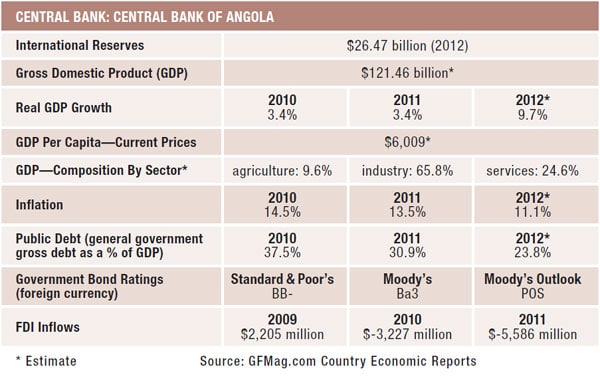

Promise and potential are two words often used to describe Angola. This sub-Saharan country of nearly 21 million people boasts enormous oil riches, a young population and a pace of economic growth (real GDP growth of 9.7% in 2012) that is the envy of the rest of the world. Yet, still scarred by a devastating, 27-year-long civil war and rife with corruption and income inequality, Angola continues to rank toward the bottom of various international benchmarks and is thought of as a difficult country in which to do business.

Despite these contradictions, Angola is now believed to be moving in the right direction, albeit in fits and starts, and the government is viewed as making a real push to consolidate growth, develop the economy beyond oil and shore up the countrys institutions.

After the end of the civil war in 2002, Angolas economy grew at an average rate of more than 10% a year, although there have been considerable ups and downs in growth since, which mirrored the trajectory of commodity prices and international demand for oil during the crisis years. Economic growth is expected to reach 7.8% this year. More recently, Angola has enjoyed moderate levels of inflation, a stable exchange rate and strong fiscal and external positions.

|

|

|

Since the government hopes to start floating international sovereign debt issues this year, it is attempting to codify investment and business regulations in a way that will seem more proper and orderly to rating agencies, says Karanta Kalley, chief economist for sub-Saharan Africa at global research firm IHS Global Insight.

The nuts and bolts of macroeconomic management have unquestionably improved and seem not to present much serious risk at the present time.

A TWO-SPEED ECONOMY

But this remarkable performance comes with caveats. As of 2012, the oil sectordriven mainly by demand from China because Angola is, after Saudi Arabia, its second-largest supplieraccounted for 46% of GDP and 96% of exports.

Additionally, Angola ranks 179th out of 189 countries in the World Banks 2014 Doing Business report, 142nd out of 148 in the latest report of the World Economic Forum, and 153rd out of 175 in Transparency Internationals 2013 Corruption Perceptions Index. In fact, a small elite has been reaping almost all of the rewards of economic growth thus far.

Angola is now one of the most prosperous sub-Saharan countries in terms of GDP per capita, says Kalley. At the same time, inequality has not abated, quite possibly becoming more severe. With two-thirds of the population under 25 years of age, roughly another two-thirds living on less than $2 a day, and an unemployment rate of 26%, Angola is a tale of two countries, and authorities are increasingly feeling the heat for this two-speed, oil-dominated growth.

Angola is not a country that has seen a lot of political unrest since the end of the war in 2002, but in the past year or two there have been more urban protests, and the government is quite worried about them, says Philippe de Pontet, director, Africa, at global political risk research and consulting firm Eurasia Group. A lot of [the protests are] driven by perceptions that living standards are declining, the awareness of the wide gap between the upper class and everybody else, and issues of employment.

|

|

|

The long-standing government of president Jos Eduardo dos Santos, in power since 1979, has enjoyed only limited success in addressing these issues. They have launched youth job initiatives, public works to create jobs, housing stipends and public investment to build up middle-income and lower-middle-income housing in the cities, says de Pontet. So some resources are being deployed, but not enoughits a mixed record.

However, in the past couple of years officials in Luanda have worked hard to try to buttress Angolas fledgling banking system in the hope of injecting liquidity into the economy and encouraging lending to local businesses.

NO FX ARMAGEDDON

A new law, the Foreign Exchange Regulations Applicable to the Oil Sector, came into effect in July 2013. In its final version, it requires oil companies in the country to pay all suppliers, salaries and taxes in kwanza via bank accounts in Angola.

In the past most of these transactions were carried out in US dollars. By all available reports, the law has been enforced consistently, bringing in a small revenue (bank fee tax) to the government but, more importantly, encouraging proliferation of kwanza-based transactions, supporting the currency and helping Angola achieve a record-high level of foreign reserves at $34 billion for 2013, says Kalley.

International oil companies have long worried that Angolas banks would not be able to cope. The expectation was always that the law would have some problems, and there have been some frustrations in terms of bottlenecks and slowness in the processing of payments, says Alex Vines, head of the Africa program at London-based think tank Chatham House. But it hasnt been the kind of Armageddon that the industry feared.

|

|

|

The Angolan authorities hope to develop the economy beyond oil. The good news is that the non-oil sector is, on average, growing faster than the oil sector, says Martin Hercules, head of Commerzbanks office in Luanda. According to government estimates, in 2013 the non-oil sector grew roughly 6.5% and the oil sector 2.6%.

These developments are hopeful signs in terms of domestic private investmentwhich is lagging at around 3% of GDP versus a regional average of 13%and luring foreign companies to Angola, although experts warn that operating here, while potentially profitable, is not easy.

Foreign companies that do business in Angola must have a lot of persistence and patience, says professor Anne Pitcher from the department of African American Studies at the University of Michigan. Almost everything an entrepreneur in the non-oil sector needs to do to set up a business takes time.

At the end of 2012 the Angolan government established a $5 billion sovereign wealth fund to harness oil revenues in yet another attempt to diversify the countrys economic base.

The SWF vehicle is still at a preliminary stage operationally, says Kalley. Yet, the fund has attracted controversy because president dos Santos appointed his son [Jos Filomeno dos Santos] chairman.

There is so much potential in Angola, says professor Pitcher, but with so many aspects of the political economy that need to be addressed, it is hard to know where to start.