MIRACLE WORKERS REACH END OF THE ROAD

By Gordon Platt, Antonio Guerrero and Anita Hawser

Boosting employment and production are the elusive goals of today’s central bankers.

If it’s broke, fix it. Central bankers are taking on new activist roles with added responsibilities for promoting economic growth, as well as financial stability. With fiscal stimulus off the table in an age of austerity, the central banks of the world are entering the trenches and buying up risky assets and in some notable cases, including Switzerland and Japan, entering into the currency wars with massive intervention.

Even the European Central Bank (ECB), whose sole mandate is to fight inflation, is purchasing the debt of countries such as Spain and Italy to keep yields from rising and contagion from spreading. Meanwhile, the legacy central banks of the eurozone, such as the once powerful German Bundesbank, retain their bloated staffs—there are still 9,000 Bundesbankers—but lack the power to print money or do much else, outside of administrative and operational functions.

To its credit, the Bundesbank may have found a new role as public advocate amid the debt crisis swirling in Europe. The eurozone’s rescue plan, which includes expanded powers for the European Financial Stability Facility, will weaken the foundations of the currency union and increase the tendency of member countries to build up debts, the Bundesbank warned in its August monthly report, even as German chancellor Angela Merkel was trying to drum up support for the proposal within her own government.

While criticizing the ECB, the Bundesbank itself has been lending hundreds of billions of dollars to the central banks of Spain, Portugal, Greece and Ireland since the financial crisis hit. As of the end of last year, the Bundesbank was owed $470 billion from other central banks.

No Magic Wand

Meanwhile, it was revealed in August that the US Federal Reserve provided as much as $1.2 trillion in public money to banks and other companies between August 2007 and August 2010 to fight the credit crunch, eclipsing the $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program that allowed the Treasury to purchase underwater assets from financial institutions.

Following a month of relentless selling, the financial markets rallied in late August in anticipation of a miracle from Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, who was expected to wave a magic wand in a widely anticipated speech in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, and make the stalled US economy all better. Instead, Bernanke spoke of the limits of the Fed’s powers and signalled that the US central bank would not take any immediate action to boost growth.

“The country would be well served by a better process for making fiscal decisions,” Bernanke said. The political brouhaha over raising the US debt ceiling had disrupted the financial markets and probably the economy as well, he added.

“Most of the economic policies that support robust economic growth in the long run are outside the province of the central bank,” the Fed chief said. Bernanke simply repeated that the Fed had a range of tools that could be used to provide additional monetary stimulus, while a third round of quantitative easing was not mentioned. He already had promised to keep interest rates exceptionally low, at least until mid-2013, and said the Fed would do anything it can to support the economy.

The Fed is also facing criticism from Republican presidential candidates, such as Texas governor Rick Perry, who said he would consider it treasonous if Bernanke “prints more money between now and the election” in 2012.

Many central banks with large foreign currency reserve positions are continuing to diversify away from the dollar. That move could accelerate in the wake of the US losing its triple-A credit rating from Standard & Poor’s.

Central bankers throughout Asia ex-Japan began normalizing monetary policies in the second half of 2009. Not only did they start mopping up excess liquidity, but they also followed with a series of interest rate increases in 2010 that have continued until recently. While economic growth in Asia recovered quickly from the global crisis and remains strong, the return to normalcy in interest rates is now being delayed.

Prudential Policies

Apart from their roles turning on and off the monetary spigots and operating payment and settlement systems, central banks also are responsible for the stability of the financial system. In the wake of the financial crisis, central bankers are increasingly aware of their responsibilities for driving prudential policies on a macro level to prevent systemic failures and global contagion.

“Central banks are taking on an expanded role in financial regulation and supervision,” says Jaime Caruana, general manager of the Bank for International Settlements. “These responsibilities bring with them new powers, but also new institutional setups that remain to be worked out in detail.”

In a speech in July at the South African Reserve Bank’s 90th anniversary seminar in Pretoria, Caruana warned that unusually and persistently low interest rates, together with the provision of ample funding, could delay the incentives to adjust and recognize losses. “Over time, the inflation fighting credibility of central banks is likely to suffer if they pursue this type of monetary policy in an environment of high public debt and rising commodity prices,” Caruana says. “The well-known arguments for central bank independence in the context of price stability apply with even greater force in the context of financial stability.”

Financial stability objectives are difficult to quantify, making accountability harder to achieve. A central bank’s exercise of its new powers needs to be underpinned by arrangements that safeguard its operational independence, Caruana says.

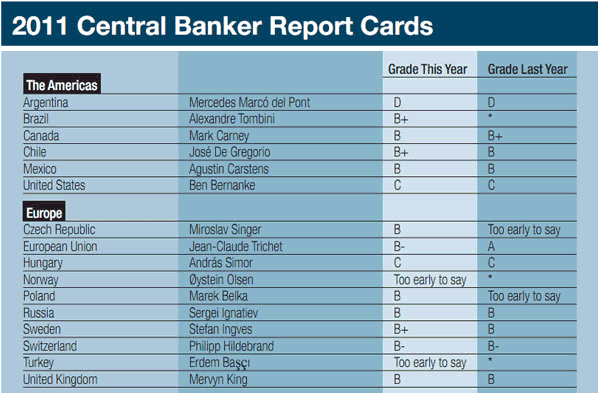

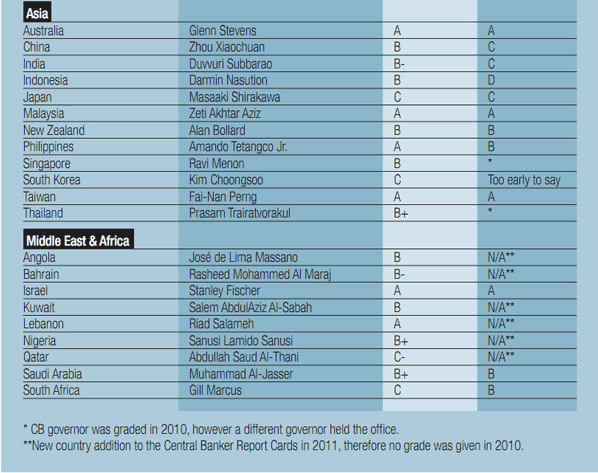

In our Central Banker Report Cards, published annually by Global Finance since 1994, we grade central bankers of key countries on an “A” to “F” scale for success in areas such as inflation control, economic growth goals, currency stability and interest rate management, and their determination to stand up to political interference and maintain their independence.

We commend those central bankers who have performed well in the past 12 months, making difficult and controversial decisions under trying circumstances.

We also highlight the shortcomings of those who have complied with the demands of the political officials who appointed them and who have followed wrong-headed policies. Nobody failed, although a few came close.