GREEN PROFITS

By Denise Bedell

Companies have long been working on creating sustainable internal operations. With growing recognition of the symbiotic buyer-supplier relationship, they are now moving those efforts into their supply chains—and reducing costs in the process.

There has long been a focus on triple-bottom-line company evaluation—or evaluation of a firm’s economic performance, and social and environmental impact. Many investors now take it into account in making investment decisions and many companies include a corporate responsibility report as part of their annual reporting.

The advantages of sustainability from a corporate perspective are manifold. First, cost reduction through increased efficiency. Second, reputational plaudits from both the market and from customers. Third, the increased brand value can give the company a competitive edge. Fourth, improved risk management.

But when that process stops at the boundaries of the company proper—and does not extend upstream or downstream from the firm—it can reduce the value gleaned from those efforts. What customer is going to applaud a firm that reduces its carbon footprint at home, only to sell goods supplied by manufacturers that use highly energy-consumptive production processes?

Perhaps more importantly from a corporate perspective, by helping suppliers to increase efficiency and reduce their cost of production, the company should see some of the upside by negotiating better prices and thus reduce their own costs.

Broader Risk Management

The need to build sustainability into supply chains also came into clear focus during the crisis of 2008-2009. Companies found that their critical suppliers were not always in the best of financial health, and when key suppliers folded unexpectedly, buyers were left dealing with the outcome. Sustainability is not just about social or environmental programs but also about creating an end-to-end product chain that is efficient, secure, well-capitalized, and around for the long haul. Thus, sustainable supply chain programs should be included as part of broader risk management efforts.

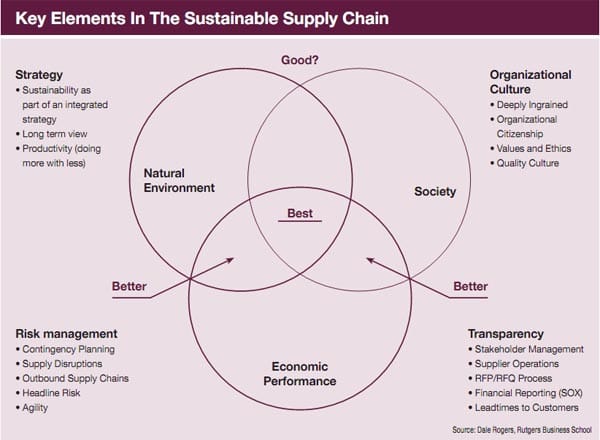

Dale Rogers, professor, logistics and supply chain management at Rutgers Business School, noted in a recent paper: “Clearly, a company cannot stay in business very long without profitability.” But he said that this should not be the only measuring stick. There must be a balance between that goal and “doing the right thing”.

However, these two goals are not necessarily at odds. Rogers added: “Using fewer resources can also lower costs in both the short run and long run. So it is not enough to think about economic performance or the environment, it is much better to think about the junction of both.”

Roots In Compliance

Companies historically looked at this through the lens of compliance. It cost money, took time, and companies generally put forth the minimum effort necessary to reach compliance.

But in recent years there has been a shift as firms recognize the value of green initiatives. They see the opportunity to optimize supply chain practices using green drivers as a backdrop. By looking at the whole cycle—from product design to distribution and sales—it provides cost reductions, risk reduction, brand enhancement and competitive advantage.

“[Companies] are working with suppliers in different ways, and making this a part of their everyday interactions”

“There is a lot going on upstream, but downstream is also a focus” – Eric Olson, Ernst & Young

Eric Olson, with Ernst & Young’s Americas Climate Change and Sustainability Services practice, notes that companies are beginning to look outside their four walls. “They are working with suppliers in different ways, and making this a part of their everyday interactions. They are, for example, building green sustainability criteria into supplier scorecards and into requests for proposals and requests for information,” he says. The more green metrics are incorporated into overall supplier performance evaluation, the greater the penetration of these types of practices.

Companies are working collaboratively with suppliers, Olson says. “They are working with them on such things as sustainable materials sourcing and reducing the number of shipments that are required for a particular purchase order. There is a lot going on upstream, but downstream is also a focus.” For example, he points to increased focus on recycling, refurbishment and reuse.

Olson adds: “If you think about it in terms of companies wanting to save money, make money and reduce risk, some of those larger recycling efforts are clearly of benefit.” The recycling itself saves money, plus they are being used in marketing and branding efforts—which in turn drives revenue growth. Reduced cost plus revenue growth means higher margins.

For multinationals or those that source products outside their home market, companies can also take advantage of government incentive programs that are geared at building sustainability into the supply chain. For example, in the US the Export-Import Bank offers advantageous terms for firms that meet certain sustainability criteria.

Consumers are also helping to push the drive for sustainability within the supply chain, as a new generation of shoppers look more closely at content, packaging, where materials were sourced, and so on.

This is an end-to-end challenge, notes one banker. “You can’t do it within your four walls. You have to look at the whole trade ecosystem. This only works if you get production, marketing, sourcing, as well as treasury and finance involved,” he says.

Another critical ingredient to success is getting board and C-suite buy-in for such a project. The key is to demonstrate why this is a competitive and market share exercise. The banker says: “It is a growth opportunity as opposed to a compliance driven, regulatory one. Once people see the bottom line impact, you get their interest.”