‘A’ FOR EFFORT, ‘B-’ FOR RESULTS

By Antonio Guerrero, Anita Hawser and Gordon Platt

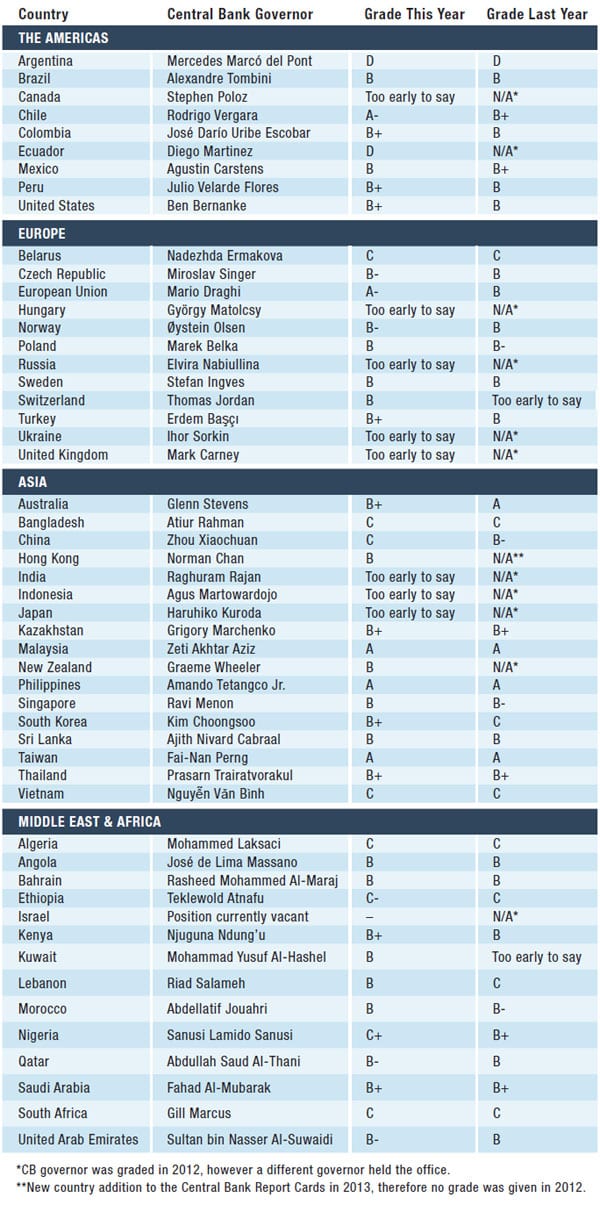

Global Finance presents its annual report on the performance of the world’s central bank governors.

There are a lot of new faces among the world’s major central bank governors, with more to come in the near future, including a new Federal Reserve chairman in the US.

Nearly one in five of the central bank chiefs in 52 key countries in Global Finance ’s survey were not holding their current positions a year ago. Although it is too early to grade the newcomers, there are reasons for hope that at least some of them will measure up to expectations.

India, for one, has chosen a distinguished economist, Raghuram Rajan, to head its Reserve Bank at a time when its economy is struggling. Rajan, who has served as director of research at the International Monetary Fund and a professor of finance at the University of Chicago, is well grounded but faces an entrenched bureaucracy. He foresaw the global financial crisis and warned of it in a speech at Jackson Hole, Wyoming (the central bankers’ summer watering hole), in 2005.

The Bank of England is now headed by Mark Carney, who earned an A grade from Global Finance for his work at the helm of the Bank of Canada. He is the first foreigner to head the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, as the UK central bank is nicknamed. There is little doubt, however, that Carney will continue to excel in his new position in the City.

The Bank of Japan has embarked on a bold course of monetary policy easing under its new governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, who seems determined to take “all necessary steps,” as he puts it, to finally slay the dragon of deflation. Again, it remains to be seen if Kuroda will succeed in meeting the BOJ’s 2% inflation goal, but bank lending in Japan is beginning to show signs of life. It is hard to say what the Bank of China is up to, after it created a tight-money crisis earlier this year and then backed off in late June.

Meanwhile, Ben Bernanke is expected to relinquish the reins of power at the Federal Reserve when his term expires at the end of January. The Fed is ready to begin tapering its purchases of bonds, as the US economy shows signs of entering sustainable, if somewhat feeble, growth.

The challenges of orderly withdrawal from quantitative easing, or QE, will be complicated, according to former Fed chief Paul Volcker. “The still-growing size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet implies the need for, at the least, an extended period of disengagement [from QE],” he says.

A reading of history suggests that in the US and elsewhere “the temptation has been strong to wait and see before acting to remove stimulus and then moving toward restraint. Too often the result is to be too late, to fail to appreciate growing imbalances and inflationary pressures before they are well ingrained,” Volcker said in late May, while accepting the Economic Club of New York’s award for leadership excellence.

The latest data from Europe suggest that the long recession there may have ended, but it is too soon to say for certain. GDP rose by 0.3% in the euro area in the second quarter, compared with the previous quarter, but it fell by 0.7% from the second quarter of 2012. The business-cycle dating committee of Europe’s Centre for Economic Policy Research will make the official call on the recession’s end.

Europe is not out of the woods yet by any means, but it has the luxury of a seasoned central banker in Mario Draghi, who has held things together with his promise to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Global Finance has been publishing Central Banker Report Cards since 1994, grading central bankers of key countries on an “A” to “F” scale. The criteria include such areas as inflation control, economic growth, currency stability and interest-rate management, as well as the determination of central bankers to protect their independence in the face of political interference.

All in all, this year’s class of central bankers has done a fairly good job of restoring financial and economic stability—with plenty of room for improvement in some cases. The average grade was a B-, the same as last year. There were three A grades (all in the Asia-Pacific region), as well as two A-minuses and two D grades. Nobody failed.

THE AMERICAS

ARGENTINA

Mercedes Marcó del Pont

GRADE: D

Marcó del Pont continues to facilitate the administration’s unchecked access to foreign reserves. She was put at the central bank’s helm after her predecessor resigned during a row with president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner over the president’s push to tap reserves to pay government debt. The administration is printing money to meet its obligations, boosting inflation to near 20%, while also intervening in foreign exchange markets to prop up a battered peso. Market confidence continues to plummet; economic growth stagnated to just 1.9% in 2012.

BRAZIL

BRAZIL

Alexandre Tombini

GRADE: B

The Brazilian economy has turned sluggish and lost much of its previous luster, despite extensive policy moves. Tombini stepped up efforts to prop up the currency, though taking a more innovative approach that involves actions in the futures market. The move has allowed Brazil to keep its $375 billion in foreign reserves intact. However, as a member of the administration’s economic team, Tombini shares partial responsibility for Brazil’s marked economic slowdown.

CANADA

CANADA

Stephen Poloz

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Poloz, former chief executive of Export Development Canada, is no stranger to the Bank of Canada. He spent 14 years at the central bank earlier in his career as an economist. It remains to be seen, however, if he can equal the skillful handling of monetary policy demonstrated by his predecessor, Mark Carney, who now heads the Bank of England. So far, Poloz has opted for a continuity of policy, with the Bank of Canada keeping rates on hold at its July 17 policy meeting. The bank also retained its policy of “forward guidance,” which hints that the next move in rates will be upward, although that may not happen until well into next year.

CHILE

CHILE

Rodrigo Vergara

GRADE: A-

Vergara, appointed by president Sebastián Piñera in 2011, is one of Latin America’s most experienced central bank chiefs. He is a former adviser to the IMF, World Bank, Inter-American Development Bank and the United Nations and has worked closely with the president on anti-poverty plans. Despite a recent slowdown, the Chilean economy continues to beat forecasts, and the jobless rate is still dropping in the world’s largest copper producer. Policymakers predict the economy will grow 4% to 5% in 2013, partly owing to Vergara’s steady policies.

COLOMBIA

José Darío Uribe Escobar

GRADE: B+

Colombia is Latin America’s major turnaround story, shedding much of its previous image linked to drugs and violence. Uribe’s prudent policies since taking the bank’s helm in 2005 are partly credited for Colombia’s success. The central bank has cut the benchmark interest rate to the lowest level in the region, while the Colombian peso is Latin America’s best-performing currency. Uribe has also avoided inflationary pressures. Increased investor confidence has translated into strong investment flows, with Colombia now back on the radar for global market players.

ECUADOR

Diego Martinez

GRADE: D

At 34 years old, Martinez is one of the world’s youngest central bankers. As a supporter of orthodox left-wing policies, Martinez, appointed in January 2013, is expected to foster greater state intervention in the nation’s economy. The central bank lost its autonomy via a constitutional referendum in 2008; president Rafael Correa has said the bank is irrelevant, and a dollarized economy leaves little room for monetary policy moves. Martinez is Correa’s sixth central banker in as many years. Fortunately, the oil-driven economy remains in good shape.

MEXICO

Agustín Carstens

GRADE: B

After losing a bid to replace Dominique Strauss-Kahn as head of the IMF, Carstens has focused strongly on reviving Mexico’s sluggish economy, though results remain less than desirable. The central bank has cut its 2013 GDP growth forecast to 2%-3%, and the outlook remains mixed. With the US still taking in 80% of Mexican exports, the US slowdown remains a major factor. However, Carstens and the Enrique Peña Nieto administration appear to be laying the groundwork for future growth, sparking a rebound in investor confidence.

PERU

Julio Velarde Flores

GRADE: B+

The Peruvian economy is still one of Latin America’s star performers, with low debt, close to $77 billion in international reserves and domestic consumption rising amid middle-class growth. Investor confidence is running high, prompting foreign buyers to move 58% of the domestic bond market. The central bank predicts GDP will expand by 6.1% in 2013 and by an average of 6.5% between 2014 and 2016. Velarde’s policies, since his appointment in 2006, have supported growth and shielded the financial system from future shocks.

UNITED STATES

UNITED STATES

Ben Bernanke

GRADE: B+

Bernanke, a student of the Great Depression, will be remembered for using unconventional means to ensure that monetary policy provided enough economic stimulus to keep the US from having to relive the 1930s. As Bernanke prepares to end his second term at the end of January 2014, however, he leaves his successor backed into a corner. Trying to unwind years of massive stimulus without triggering a big rise in interest rates will be a delicate procedure. Bernanke deserves credit, however, for keeping the US economy from melting down and for introducing greater transparency in monetary policy. He introduced quarterly press conferences, a 2% inflation target and forward guidance linked to an unemployment threshold.

EUROPE

BELARUS

Nadezhda Ermakova

GRADE: C

Ermakova will have to pull out all the stops to knock Belarus’s international reserve assets into shape to meet the country’s external debt obligations. According to newspaper reports, she has not ruled out a eurobond issue or using a portion of a potential loan from Russia to shore up reserve assets. Although inflation is declining, in a June 12 report the IMF intimated that the central bank could do more to keep inflation on a downward trajectory by more tightly managing domestic demand.

CZECH REPUBLIC

CZECH REPUBLIC

Miroslav Singer

GRADE: B-

With its main policy rate at “technical zero,” the only other mechanism at Singer’s disposal to help stimulate a sluggish economy is intervention in the foreign exchange markets. It is an idea that the Czech National Bank has toyed with all year, but Singer reportedly stated earlier in the year that future intervention may not be needed. With GDP growth in the short term likely to remain negative and inflation still below the target range, one can only hope that Singer takes decisive action some time soon.

EUROPEAN UNION

EUROPEAN UNION

Mario Draghi

GRADE: A-

Last year we praised Draghi for his efforts to do “whatever it takes” to preserve the single currency. Even if his bond-buying program hasn’t helped all ailing eurozone countries, Draghi has at least won the war of words, giving the markets the assurances they needed to see some end in sight for the enduring eurozone sovereign debt crisis. Europe and Draghi are not out of the woods yet though, and as other central banks start to tighten monetary policy, the ECB president’s next move will be watched very closely.

HUNGARY

HUNGARY

György Matolcsy

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Matolcsy’s appointment to the top post at Magyar Nemzeti Bank in March was shrouded in controversy. A former deputy governor who resigned claimed that the central bank’s new administration lacked the qualifications and experience to do the job. Questions also remain as to the central bank’s independence, with president Viktor Orbán making no secret of his disdain for former governor András Simor. Matolcsy, a former minister of the economy under Orbán, has continued to cut the base rate as the level of economic output has remained sluggish.

NORWAY

Øystein Olsen

GRADE: B-

Norges Bank has maintained its key policy rate at 1.5% since last year in view of low inflation and the general trend of lower external interest rates. Olsen surprised markets in June by stating that the key policy rate was likely to remain at the current level, or somewhat lower, in the year ahead. The value of the krone fell sharply. Given signs of recovery in the eurozone and the US, is Olsen being too cautious and relentless in his pursuit of inflation targeting?

POLAND

POLAND

Marek Belka

GRADE: B

The National Bank of Poland has spent most of this year gradually reducing its key policy rate in light of weaker economic data. The key reference rate now stands at 2.5%, and despite divisions within the Monetary Policy Council throughout the year as to how much rates should be cut, by not cutting too much Belka has given himself plenty of room to maneuver if inflation should increase or economic conditions worsen.

RUSSIA

Elvira Nabiullina

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Nabiullina’s predecessor, Sergei Ignatiev, was seen as hawkish in view of his reluctance to ease rates despite a slowing economy. So far Nabiullina, who is the first woman to run the central bank of a G8 economy, has maintained her predecessor’s hawkish stance when it comes to rates, but she may come under pressure to reverse that stance, as the pace of economic growth remains low. At the same time, she will need to maintain her predecessor’s resolute focus on inflation, which continues to exceed the target range.

SWEDEN

SWEDEN

Stefan Ingves

GRADE: B

Having cut the repo rate to 1%, its lowest level since 2011, at recent meetings the Riksbanken kept rates on hold. Ingves hopes he has done enough to stimulate economic activity while at the same time keeping rates high enough to avert a crisis, as Swedish households’ level of indebtedness continues to rise. That has meant, however, that Ingves has spent less time focusing on doing something about the strong krona.

SWITZERLAND

SWITZERLAND

Thomas Jordan

GRADE: B

Jordan is resolute when it comes to defending the currency floor of SFr1.20 per euro. He stated that appreciation of the Swiss franc would compromise price stability and would have serious consequences for the Swiss economy. To enforce the minimum exchange rate, he is ready to buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities, if needed. Despite his efforts, however, the franc is still overvalued, and increased FX activity has increased the financial risks on the bank’s balance sheet.

TURKEY

Erdem Baçi

GRADE: B+

Baçi has demonstrated a more flexible approach to monetary policy, given the uncertainty that persists in the global economy. Combining the bank’s unorthodox policy of raising reserve requirements instead of rates when needed with an interest rate corridor appears to have paid off. The Turkish economy, which demonstrated all the signs of overheating, has slowed but not too much, and Baçi has been able to keep credit growth in check by tightening reserve requirements and moving the interest rate corridor up or down as required.

UKRAINE

Ihor Sorkin

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Before becoming governor in January, Sorkin was deputy head of Ukraine’s central bank. He has continued his predecessor’s policy of stimulating economic growth by encouraging bank lending. In August the central bank lowered the discount rate for the second time this year, reducing it from 7% per annum to 6.5%. This follows a previous 0.5 percentage point cut in the discount rate to 7% per annum in June. With consumer price inflation at low levels, Sorkin can afford to be accommodative.

UNITED KINGDOM

Mark Carney

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Carney’s governorship of the Bank of England was one of the most anticipated central bank appointments in a major G8 country in recent history. He has already courted controversy by announcing that Jane Austen would be on the face of the new Bank of England £10 note. He managed to steer the Monetary Policy Council’s focus away from talk of further quantitative easing toward unemployment as a gauge for what the central bank will do next, when it comes to much-anticipated rate rises. That recalibration appears to be some way off, though.

ASIA-PACIFIC

AUSTRALIA

AUSTRALIA

Glenn Stevens

GRADE: B+

Stevens, a former Grade-A central banker, undermined the Australian dollar in late July, when he said: “The recent decline in the exchange rate seems to make sense from a macroeconomic perspective, [and] it would not be a major surprise if a further decline occurred over time.” The Reserve Bank of Australia cut its policy rate by a quarter point to 2.75% in May, as it became apparent that the mining boom had ended and China’s growth had slowed. It cut the rate again in August, to a record low 2.5%, acting for the first time ever during an election campaign.

BANGLADESH

Atiur Rahman

GRADE: C

The Bangladesh government in April granted Rahman an additional three years as central bank governor. He has led the bank since 2009, with a focus on reducing poverty. Rahman came to the defense of microcredit lender Grameen Bank at a time when the government advocated breaking it up into 19 pieces. It was also on his watch, however, that Sonali Bank, Bangladesh’s largest state-run bank, became embroiled in the country’s largest-ever banking scandal. In its first rate cut since 2009, Bangladesh Bank lowered its repurchase rate in January to 7.25% from 7.75%.

CHINA

Zhou Xiaochuan

GRADE: C

Zhou is the longest-serving central bank chief in China and normally doesn’t like to rock the boat. He caused big waves in June, however, when he orchestrated a record liquidity squeeze and was later forced to backtrack in the face of turbulent markets. The main objectives of the People’s Bank of China are to maintain currency stability and to promote economic growth. The central bank wants to rein in the shadow banking industry, but any attempts to curb credit could make it even more difficult to reach this year’s 7.5% GDP growth target.

HONG KONG

Norman Chan

GRADE: B

Chan has been CEO of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority since 2009. The authority’s main objectives are currency and financial stability. Chan also works to promote Hong Kong as an international financial center and manages the Exchange Fund. The HKMA, a de facto central bank, uses the fund to manage its assets and to defend the Hong Kong dollar’s peg to the US dollar. The fund sustained an investment loss of $3.25 billion in the second quarter, owing to its large holdings of US Treasuries, as well as volatile conditions in the foreign exchange market.

INDIA

Raghuram Rajan

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Rajan, former chief economic adviser in India’s Finance ministry, has served as chief economist and director of research at the International Monetary Fund and a professor of finance at the University of Chicago. He became governor of the Reserve Bank of India in September, succeeding Duvvuri Subbarao, whose five-year term ended with the economy in a state of turmoil. Rajan’s immediate goals are to shore up the sinking rupee and to restore growth momentum to the economy. Rajan faces a huge task and admits that he has no magic wand. Analysts have high hopes, however, that he will implement the financial sector reforms he has long advocated.

INDONESIA

Agus Martowardojo

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Martowardojo was Indonesia’s Finance minister in March, when he was selected as the next central bank governor, succeeding Darmin Nasution, whose term ended in May. Under Martowardojo, Bank Indonesia has moved quickly to manage inflation expectations and support the weakening currency. The central bank raised its policy rate by a half point in July, following a quarter-point increase in June. It also took measures to limit lending to the property sector, amid fears the economy was overheating. Economists say there could be more rate increases in the months ahead.

JAPAN

Haruhiko Kuroda

GRADE: TOO EARLY TO SAY

Kuroda has responded aggressively to orders from prime minister Shinzo Abe for the Bank of Japan to achieve an inflation target of 2% to stimulate economic growth. At its meeting in April, the bank said it would increase its purchases of government bonds by more than $500 billion a year. The previous policy of incremental easing hadn’t been enough, Kuroda said. “This time, we took all necessary steps to achieve the target.” Japan’s GDP rose 3.6% in the second quarter, thanks to fiscal and monetary stimulus, as well as a weak yen. The BOJ has committed to doubling its monetary base by 2014. Kuroda is urging the government to raise the 5% sales tax next April.

KAZAKHSTAN

Grigory Marchenko

GRADE: B+

Marchenko, governor of the central bank of Kazakhstan from 1999 to 2004 and from 2009 to the present, says the oil-rich country relies on $90 per barrel oil to meet its current budget goals. Higher oil production and a rebound in the agricultural sector resulted in real GDP growth of 5.1% in the first half of 2013, while inflation of 5.9% was less than forecast. Nonperforming loans represent about 30% of total lending. A fund run by the central bank has begun buying up bad loans, but some commercial banks are holding out for better deals.

MALAYSIA

MALAYSIA

Zeti Akhtar Aziz

GRADE: A

Zeti not only has ensured orderly financial market conditions and a strong economy in Malaysia, but she also has led the fight to enhance access to financing for SMEs. Bank Negara Malaysia’s main objective is keeping inflation low and stable, thereby defending the purchasing power of the ringgit. The central bank is also responsible for maintaining financial stability. The bank has kept its official rate unchanged at 3% this year. Malaysia’s GDP is expected to grow by about 5% this year, while inflation is below 2%. Zeti is a leading proponent of Islamic finance. She says its role has expanded to become significantly more globalized.

NEW ZEALAND

Graeme Wheeler

GRADE: B

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has kept its policy rate on hold at 2.5% so far this year. The bank’s main concerns are a buoyant currency and an overheating housing market. It intervened in the currency market in April in an attempt to weaken the currency, which has since retreated. Wheeler, a former managing director of operations at the World Bank, succeeded Alan Bollard as governor of the Reserve Bank in September 2012. Wheeler says the central bank will need to remove stimulus in the future, but expects to hold rates unchanged through the end of 2013.

PHILIPPINES

PHILIPPINES

Amando Tetangco Jr.

GRADE: A

Tetangco’s policies have won the confidence of investors and have helped to make the Philippines the star economy of Asean. The central bank has held its official rate at 3.5% this year, but cut the special deposit accounts rate to encourage banks to increase lending. It says a weakening peso poses inflation risks, and it raised its inflation forecast in July to 3.3% for 2013, and 4% for next year. The Philippines won its first investment-grade ratings this year from Fitch Ratings and Standard & Poor’s. Moody’s Investors Services is considering a possible upgrade.

SINGAPORE

Ravi Menon

GRADE: B

Menon in June began an additional two-year term as managing director of the Monetary Authority of Singapore. The MAS manages the Singapore dollar exchange rate against a basket of currencies to keep it within an undisclosed target band. It lowered its inflation forecast in July to a range of 2% to 3% in 2013 and kept its economic growth forecast unchanged at 1% to 3% for the year. “For the first time in three years, inflation has come down closer to historical trends and within MAS’s comfort range,” Menon said.

SOUTH KOREA

SOUTH KOREA

Kim Choongsoo

GRADE: B+

The Bank of Korea cut its policy rate a quarter point to 2.5% in May and has since held steady at that level. It forecast in its August statement that the global economy would sustain its modest recovery, primarily owing to improvements in the US economy. South Korea’s economy grew at its fastest pace in two years in the second quarter, with GDP up 2.3% from a year earlier on government stimulus and a rise in consumer spending. Exports account for nearly half of the country’s total economic output. Inflation has remained comfortably below the central bank’s target range of 2.5% to 3.5%.

SRI LANKA

Ajith Nivard Cabraal

GRADE: B

The Sri Lanka central bank lowered its target short-term borrowing rate by half a point to 7% in May, following a quarter-point cut in December 2012. Cabraal is seeking GDP growth of 7.5% this year, up from 6.4% last year. The central bank also increased the reserve maintenance period to two weeks from one week, to give commercial banks more flexibility in managing their liquidity. The central bank cut the statutory reserve ratio by two percentage points to 6% on July 1, to enable banks to reduce lending rates further.

TAIWAN

TAIWAN

Fai-Nan Perng

GRADE: A

Taiwan’s GDP rose 2.3% in the second quarter from the same period last year. The central bank has kept interest rates unchanged so far this year and its inflation rate has remained low and stable, and unemployment has declined steadily from 2009. The introduction of an offshore renminbi market in Taiwan this past February is expected to increase business activity and help Taiwan develop as a financial hub. Taiwan’s renminbi deposits increased from zero to Rmb76.9 billion at the end of July.

THAILAND

Prasarn Trairatvorakul

GRADE: B+

The Bank of Thailand cut its official repurchase rate by a quarter point to 2.5% in May, as economic growth slowed. In July the central bank cut its forecast for GDP growth this year to 4.2% from 5.1%. Finance minister Kittiratt Na-Ranong pressured the central bank to cut its rate further, but Prasarn warned about the country’s rising household debt and a possible credit bubble. The government increased the minimum wage and gave big subsidies to rice farmers to stimulate growth after the economy was devastated in 2011 by floods that killed 815 people and inundated industrial areas.

VIETNAM

Nguyn Vn Bình

GRADE: C

The State Bank of Vietnam devalued the dong by 1% against the dollar at the end of June and lowered the ceiling on dollar deposits to help improve the balance of payments and increase foreign currency reserves. The moves came one day after the government had announced a $1.4 billion trade deficit in the first half. GDP rose at a 5% rate in the second quarter. The central bank cut its repurchase rate to 5.5% from 6% in July, although the IMF urged it to focus on fighting inflation.

MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA

ALGERIA

Mohammed Laksaci

GRADE: C

With the crucial energy sector in decline, Algeria’s economy is struggling with slow growth and rising inflation. Laksaci has kept Bank of Algeria’s deposit rate unchanged at 1.75%, saying that monetary policy cannot fix rising food prices. Meanwhile, oil and gas exports are slumping, while auto imports are rising, putting pressure on the balance of payments. In January, Algerian Special Forces ended a four-day siege of the Amenas gas complex by jihadists, which resulted in the deaths of 37 expatriate technicians and most of the 40 attackers. Foreign oil companies are still reluctant to send staff back to the plant amid concerns about security.

ANGOLA

José de Lima Massano

GRADE: B

The National Bank of Angola last changed its lending rate in January, lowering it by a quarter point to 10%. However, at its meeting on June 28, the central bank reduced the required reserve ratio on commercial bank deposits by five percentage points to 15%. Angola’s GDP rose about 8% in 2012, after several years of slow growth following the global financial crisis. The country’s dependence on oil revenue leaves it exposed to external shocks, but the recent fast growth in the economy has prompted a rapid expansion of the financial industry. An inflation rate above 9% remains a concern.

BAHRAIN

Rasheed Mohammed Al Maraj

GRADE: B

Bahrain, which pegs its dinar to the dollar, has kept its 2.25% overnight repurchase rate unchanged since 2009. The country needs high oil prices to balance its budget and has become reliant on aid from its wealthy Arab Gulf neighbors. The central bank has kept a close watch on the financial sector, which remains relatively stable and accounts for about 17% of GDP. However, more than two years of social unrest have taken a toll on the tourism industry. Bahrain issued a $1.5 billion bond in late July, which was heavily oversubscribed and performed well in the secondary market.

ETHIOPIA

Teklewold Atnafu

GRADE: C-

Ethiopia’s state-led development model has produced fast GDP growth rates, high inflation and paved roads. The largely agriculture-based economy grew about 7% last year, but inflation was in double digits. The central bank finances government spending, while monetary policy is limited to foreign exchange market intervention, the World Bank said in a recent report. Ethiopia should rethink its current monetary policy and introduce open-market operations, if it wishes to attain single-digit inflation, the report said. The savings rate is at a 30-year low, and state-owned enterprises are crowding out private-sector borrowers.

ISRAEL

Position Currently Vacant

GRADE: –

The Bank of Israel kept its base rate on hold at 1.25% in July to allow the impact of previous rate cuts to take effect. It cut rates twice in May and intervened in the foreign exchange market to restrain the soaring shekel. Meanwhile, the search continues for a new governor to replace Stanley Fischer, who stepped down at the end of June. Fischer, an A-grade central banker, quit in the middle of his second term. Under his watch, a new Bank of Israel law was passed in 2010, establishing a monetary policy committee to set interest rates, instead of leaving these decisions up to the governor alone.

KENYA

Njuguna Ndung’u

GRADE: B+

Kenya’s tourism, as well as its flower and vegetable exports, suffered in the wake of a major fire at Nairobi’s international airport in August. Before the blaze, tourist arrivals were expected to rise by 4% this year, amid political stability and relatively strong economic growth. The IMF forecast GDP growth of 5.6% in 2013, following growth of 4.2% last year. The central bank kept its interest rate unchanged at 8.5% in July, amid a stable exchange rate and a lack of inflationary pressures. The monetary policy committee cut the rate by a full point in May to support the economy following a peaceful presidential vote in March.

KUWAIT

Mohammad Yusuf Al-Hashel

GRADE: B

Near-record oil production and an expansionary fiscal policy boosted Kuwait’s gross domestic product growth rate to 6.1% last year. Growth is expected to slow this year, owing primarily to a contraction in the oil sector. The Central Bank of Kuwait has held its policy rate at 2% so far this year, following a half-point cut in October 2012. The July 27 parliamentary election resulted in an assembly that could work more closely with the executive branch to implement economic development projects. Kuwait has one of the least-diversified economies in the Arab Gulf.

LEBANON

LEBANON

Riad Salameh

GRADE: B

The Syrian conflict is having a negative impact on Lebanon’s economy, particularly through its effect on the tourism sector. Lebanon’s real estate and financial services industries have proved resilient, however. The central bank has provided low-interest funds to commercial banks for lending to small and medium enterprises. By managing liquidity in the banking system, Bank of Lebanon aims to meet a 4% inflation target for 2013. It is keeping interbank rates in the 2%-to-3% range. The debt-to-GDP ratio reached 134% last year and is expected to remain at that level in 2013, the World Bank forecast in June.

MOROCCO

Abdellatif Jouahri

GRADE: B

Morocco’s central bank, Bank Al-Maghrib, lowered its policy rate by a quarter point to 3% in March to support economic growth. That was the first change in the rate since 2009. The bank projects GDP growth of 4.5% to 5.5% this year, up from 2.7% last year. A major drought hurt agricultural output in 2012. The central bank said in June that its 2013 forecast for GDP assumes that the government maintains the current subsidy system. It projects inflation to average about 2.1% in 2013.

NIGERIA

Sanusi Lamido Sanusi

GRADE: C+

The Central Bank of Nigeria has kept its lending rate at a record high 12% so far this year, in an effort to support the naira currency. At its policy meeting in July, it introduced a surprise 50% cash reserve requirement on public-sector deposits, up from 12% previously, to prevent banks from taking government deposits and lending the money back to the government at a profit by investing in Treasury bills. Sanusi says he will not renew his contract when his term ends in June 2014, because the difficult decisions he has taken have annoyed too many people whose support he would need to stay in office.

QATAR

Abdullah Saud Al-Thani

GRADE: B-

Qatar’s GDP growth is expected to slow to around 5.3% in 2013 from 6.2% last year, as natural gas production is limited by capacity constraints. Qatar relies on oil and gas for 85% of its export earnings. The central bank announced new regulations in June to protect the financial sector as government spending on infrastructure projects increases ahead of 2022, when Qatar hosts the World Cup. The new rules limit banks’ securities portfolios and prevent Islamic banks from investing too heavily in real estate. So far this year, the central bank has kept its overnight lending rate unchanged at 4.5% and its overnight deposit rate at 0.75%.

SAUDI ARABIA

Fahad al-Mubarak

GRADE: B+

Al-Mubarak, governor of the Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency, is a former chairman of Morgan Stanley Saudi Arabia. SAMA sets its key policy rate, the reverse repo rate, with reference to the US federal funds rate, since the riyal is pegged to the dollar. Domestic credit growth has been rapid over the past year, reflecting a strong non-oil economy. The Saudi economy expanded at a 6.8% rate last year, but the IMF is projecting a slowing to 4.2% GDP growth in 2013. In May, SAMA created a new body—the General Department of Insurance Control—to supervise the insurance industry.

SOUTH AFRICA

Gill Marcus

GRADE: C

The South African Reserve Bank has maintained its repurchase rate at 5% so far this year. Marcus said in July that the bank “continues to face conflicting policy choices relating to rising inflation and slowing growth.” The economy was threatened by “low consumer confidence, continued output disruptions in the mining sector, electricity supply constraints and a weak global environment,” she said. The central bank cuts its forecast for GDP growth this year to 2% from 2.4%. Inflation has been running close to the bank’s upper limit of 6%.

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Sultan Nasser al-Suwaidi

GRADE: B-

The UAE’s economy grew by 4.3% last year and will grow by 3.6% this year, according to the IMF, adding that that Dubai should improve its budgeting and take tighter control of its government-related entities “to avoid setting off a new boom-bust cycle.” The UAE government is cutting back on the huge fiscal spending it undertook to get the country through the global financial crisis. The UAE dirham is pegged to the dollar, and interest rates are at historic lows.