Cool Hand Lula

He may be frustrating his more radical colleagues, but

Brazils President Lula is achieving remarkable success

with his delicate balancing act.

Each of the three times Luiz Incio Lula da Silva ran for president, his leftist platform sent chills through Brazils business community. Since winning the presidency by a landslide in 2002, however, his surprisingly orthodox policies have sparked an economic recovery and cheered investors at home and abroad. His populist comrades are, in many cases, less than thrilled.

The president ran on a Labor Party (PT) ticket but, faced with the countrys deepening recession, has had to perform a balancing act between improving the lot of his constituents and having enough money to do so without putting long-term growth and stability at risk. For many observers, he represents a new breed of Latin American populists who are just as concerned about fiscal responsibility as they are about social welfare.

Were used to thinking of populists as big-time dreamers who want to spend big money on social programs but usually do it by over-borrowing and not weighing the long-term consequences, says one Latin American banker.Lulas style is different because he wants to help his people, but hes not going to leave a bill for future generations to pay. Hes doing it responsibly, the banker notes.

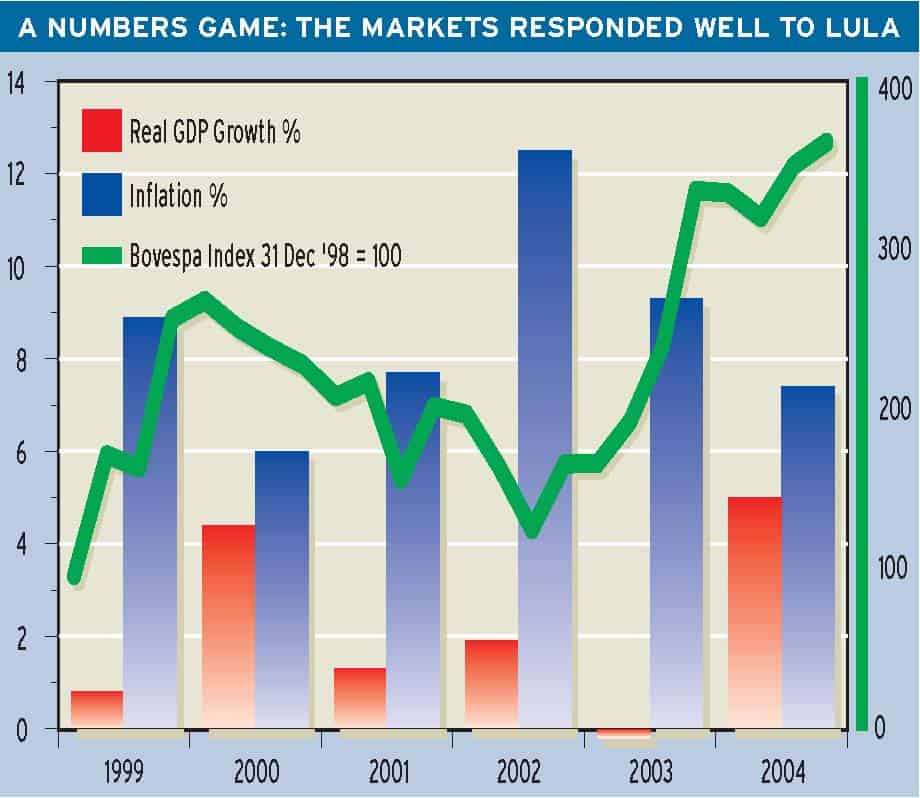

So far, Lulas strategy is paying off nicely. After a 0.2% contraction in 2003, GDP is expected to have expanded by as much as 4.5% this year. The 5.7% GDP growth during the second quarter was the highest leap since 1996. A weakened currency has contributed to an export boom that produced monthly trade surpluses of more than $3 billion in September and October.

Rebounding consumer demand sparked by increased confidence, dropping joblessness and growing credit availabilityis another contributing factor in this market of 175 million consumers. The rebound pushed industrial production up 13.1% year-on-year in August alone. Sales of furniture and electronics rose 29.4% during the first-half of the year, while auto production had soared by 45.6% by September.

On the debt side, Lulas scorecard is also favorable. The debt-to-GDP ratio fell to 53.7% in September, producing the lowest level since April 2003. Based on our expectation of an FX rate of R$3.00/US$ at end-December, we estimate that the debt/GDP ratio should end 2004 at approximately 55.5% (compared with 58.7% at end2003), estimates Credit Suisse First Boston. The bank says that, if its forecast is confirmed, this would represent the first decline in Brazils debt-to-GDP ratio from one year to the next since 1994.

Record Surpluses

In September the government raised its primary budget surplus target for 2004 to 4.5% of GDP from the previous 4.25% it had agreed to with the IMF. During the first eight months of the year, increased tax revenue catapulted the surplus to a record 5.8% of GDP, allowing the administration greater capacity to service its debt. Such accomplishments led IMF director Rodrigo Rato, during a visit to Brazil in September, to praise the governments policies, which he deemed courageous.

To keep the economy from overheating and to curb inflation, the central bank decided to raise interest rates this year for the first time since February 2003.The central banks monetary policy committee launched its tightening mode by hiking the benchmark Selic rate to 16.25% in September. Analysts predict the rate may end the year as high as 18%, depending on how oil prices and capacity expansion limitations on local industries affect inflation.

This is where Lulas political headaches begin. In order to curb inflation, one of Brazils traditional bogeys, the president has opposed calls for increased wages from a labor sectorthat says its demands had gone unmet under Lulas predecessorswhich is why they helped put him in office in the first place. The situation put Lula in an awkward and politically risky position in June, when the senate voted to discard the presidents conservative wage increase proposal in favor of a larger one that would challenge the administrations fiscal discipline.

Lula proposed an 8.3% increase, while senators sought a 14.5% adjustment.The government argued that the larger increase would boost not only its payroll but also its pension and social security payouts. Lawmakers reminded the president of his campaign pledge to double the minimum wage by the end of his term in 2007. Lula ultimately prevailed, but not without witnessing the fragility of his congressional support, despite holding control of both houses. More importantly, it was Lulawho not only ran on a la bor ticket but also founded the nations largest labor unionwho was publicly taking an anti-labor stance.

The response was swift. A series of strikes was unleashed this year to demand wage hikes of 4% to 17% above annual inflation after years of falling income levels. Metalworkers began two-hour daily work stoppages, while judiciary workers in So Paulo walked off their jobs. A strike by bank employees in October spread throughout the country. Many of the strikes reportedly had the veiled support of several of Lulas cabinet members, many of them former labor leaders themselves.

Theres been a demand for better salaries for many years, says Luis Bitencourt, director of the Brazil Project at the Woodrow Wilson Center, a Washington-based think-tank on global affairs.After inflation was put under control, these demands were largely put to rest, but now they have been revived. Bitencourt feels that while political noise surrounding the wage issue may have been heightened by politicking ahead of Octobers local electionsin which the ruling PT more than doubled the number of towns it will run, though losing two key mayoralties in So Paulo and Porto Alegrethe situation has unleashed a crisis within the party.

The Enemy Within

Although Lula has been able to hold together other parties within his coalition, much of the administrations opposition is coming from radical factions within the PT that oppose his macroeconomic rigor.They had hoped that, with their man in office, their calls for social justice would be heard in a country where 60 million people live in poverty. But when Lula began slashing personal and corporate taxes to encourage spending and capital investments, it was evident that the pot of funds for social spending was about to get smaller.

The PT said it would address socioeconomic imbalances as part of its election promises, and it didnt do it, notes Bitencourt, who says some PT members left the party after realizing that Lula, whom they had hoped would take a revolutionary stance, instead took a more orthodox approach. When four lawmakers opposed the governments pension reform bill last year, they went on to establish the PSOL as a left-wing opposition party.

Thats not to say that Lula has turned his back on the poor. One of his pet projects is Zero Hunger, a program to provide food to the most impoverished communities. His campaign to get large drug makers to provide hefty discounts to the governments program to provide free medication to HIV/AIDS patients is regarded as a global model. Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly this year, where he sought support for a proposal to tax financial transactions and weapons sales to fund global anti-poverty programs, Lula said poverty is the deadliest weapon of mass destruction.

Lula Takes the Long View

The difference seems to be that Lula is unwilling to run up a tab that will ultimately cause more damage than good. Lula is the type of person who can see the bigger picture, and he knows that he could give people some short-term relief now or create a solid economy that will provide them and future generations a better life, says the Latin American banker, who notes Lula himself comes from an impoverished rural family. Lula was a shoeshine boy, messenger and factory worker before becoming a labor activist.

A study by the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) shows Brazil spent $936 (1997 dollars) per capita on social programs in 2000-2001. While the figure was well above the regional average of just $494, it was equal to Chilesa much smaller countryand far below Argentinas $1,650 and Uruguays $1,494. When viewed as a percentage of GDP, Brazil also fell short at 18.8%, compared with 25.5% in Panama, 23.5% in Uruguay and 21.6% in Argentina. Naturally, Lula could safely argue that Argentinas finances have been less than stellar.

Quality, Not Quantity

The total amount spent yearly on health, education and pensions is considered by eminent social policy experts to be more than enough to eliminate indigence and substantially reduce poverty within a few years, wrote Carlos Pio, a professor of international political economy at the University of Brasilia, in a report published by Spains Royal Elcano Institute for International and Strategic Studies. The major problem associated with social policy in Brazil is not the amounts spent, but rather the lack of focus (i.e., whether the money is spent with those who really need it).

Pio suggests that to increase the effectiveness of Brazils social policies, the government must restructure the social budget in order to direct funds to the poorest sectors, condition the concession of social policy benefits to some type of capital gain for recipients, and eliminate mechanisms that allow political groups (political parties, labor unions, associations) to benefit from the distribution of social benefits.

Brazilians may finally be getting a better understanding of Lulas long-term vision. Approval ratings for the administration, which slipped from 66% last December to 51% in June, resumed an upward trend to 55% in September.The disapproval rate, according to the Ibope polling firm, fell from 42% in June to 36% in September. It appears that for Lula, putting Brazils finances in order and creating a stable economy are his best visions for helping his poorest compatriots. If now he could only get his populist comrades to agree.

THE PROTGS EMERGE

The majority of South Americans now live under left-of-center administrations of one shade or another. With democratically elected leftleaning governments in office in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela, Brazils Lula has set the new standard for his counterparts to seek social justice while maintaining fiscal responsibility.

If indeed there is now a new school of Latin American populists, then Lula is undoubtedly its headmaster. When Uruguayan business leaders were concerned about President-elect Tabar Vzquezs leftist platform, Vzquez had Danilo Astori, tapped to be his finance minister, publicly state that the incoming administration would follow pro-market policies based on Lulas. The statement was enough to ease investor concerns and get Vzquez, a practicing cancer specialist and former mayor of Montevideo, elected on a coalition ticket composed of labor unions, former communist party members and former guerrilla leaders. His victory in a first-round vote in October marked the first win by a candidate from outside the Colorado and Nacional parties, which have collectively ruled the country since the 1800s.

The fact that Vzquez has vowed to install an economic team committed to fiscal responsibility, coupled with the markets positive experience with other leftist leaders in the region (namely Brazils Lula), has allowed the market to adopt a more accommodating attitude, says a report from HSBC.

Vzquez, who lost two presidential races in the past, including a first-round win that ended in a run-off loss in 1999, faces a difficult economic environment and high expectations. Uruguays economy shrank by 11% in 2002. Although the economy is witnessing a strong recovery, some 30% of the population still lives in poverty.

The incoming administrations proposed economic policies include pursuing a consistent monetary policy to achieve growth and provide fair income distribution, establishing a floating exchange rate regime, strengthening the peso by de-dollarizing the economy, promoting free markets and encouraging joint publicprivate investment.

Controlling inflation, maintaining an adequate primary surplus and complying with debt obligations are not exclusive proposals of the right, Astori said. The administrations first steps, he noted, will be to launch a structural reform program coupled with a social emergency plan.

Vzquez may face some resistance along the way. After all, his coalition party may be less enthusiastic about fiscal conservatism at the expense of reduced social outlays. Some analysts also see trouble brewing with the business sector, as the party opposes privatization and favors centralized labor talks. The administrations legislative majority should help ease some of the growing pains.

Further north in Central America, Panamanian President Martin Torrijos, who took office in September, is another Lula protg. The 41-year-old US-educated former management consultant is the son of General Omar Torrijos, a populist and military strongman who ran the country for 13 years and is best known for negotiating the return of the Panama Canal to Panamanian control. Despite his left-leaning agenda, President Torrijos does not appear to have taken after his father and has even vowed to investigate charges of abuse committed under the elder Torrijoss regime.

We are going to show Panamanians how state resources should be used with transparency, Torrijos has said, warning that the country no longer has an abundance of funds and that people will have to adapt to this new reality. A month after taking office, labor leaders protested the governments program to overhaul the bankrupt social security system, while farmers marched on the capital to protest a proposed Panama Canal expansion that they feel would force them out of their lands.

Latin American governments are at a crossroads. When Cuban President Fidel Castro, the elder statesman of Latin Americas left wing, took a nasty fall after a speech in October, many saw it as a metaphor for the end of an era. It seems only Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez is willing to follow Castros old-school style. Fortunately, most are instead taking lessons from Lula.

Santiago Fittipaldi