NO LONGER JUST A GAME?

By Ronald Fink

The recent spate of currency devaluation will start to have a serious impact unless global leaders focus on economic fundamentals, rather than figments.

The yen is down 25% against the euro since Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was tipped to win office last November. The US dollar’s long slide against most major currencies continues, albeit with extreme ups and downs, leaving its trade-weighted average 25% lower than it was a decade ago. The Swiss have imposed a ceiling on the franc’s exchange rate since eurozone chaos sent investors jumping on its safe-haven status. And China still won’t let the renminbi float freely despite the emerging markets giant’s growing asset bubble.

It appears that global currency game playing may soon be over: A currency war—wherein countries engage in currency manipulation for competitive advantage in global trade—could be in the offing, if it hasn’t already broken out. And alarm bells are ringing in capitals around the world as a result, with more than a little pearl-clutching over the prospect of self-defeating, beggar-thy-neighbor rounds of “competitive devaluation.”

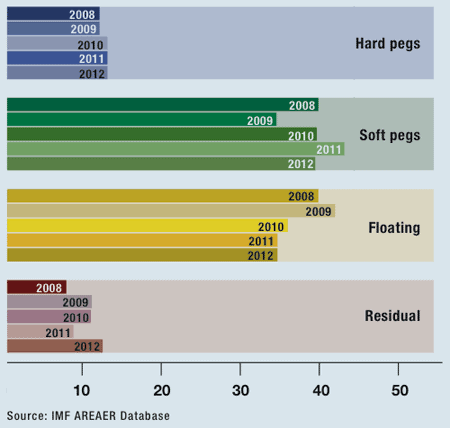

The overall proportion of countries that choose not to manage their currencies—that instead let their currencies float freely and allow market forces to determine their rate—has fallen by more than 5 percentage points since the financial crisis, from 39.9% at the end of April 2008 to 34.7% at the end of April of last year, while the proportion of those adopting currency pegs or other measures to manipulate exchange rates has risen, according to the International Monetary Fund (see chart, below).

Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann was sufficiently concerned by prime minister Abe’s aggressive pursuit of monetary easing by Japan’s central bank to issue a warning in February against the “politicization” of exchange rates and “alarming violations” of the reigning, if paper-thin, global consensus in favor of currency stability. On cue, the business press filled with articles bemoaning the prospect of trade conflict.

But the headlines fail to point out that currency war may not be the goal of policymakers, even as they make policies that cause just that. “Currency devaluation is not the objective but the effect of a policy when you run out of room to reduce interest rates or target the quantity of money in circulation,” observes Ashraf Laidi, a currency strategist for City Index, a trading firm based in London.

The broader issue is the condition of the global economy—abundantly and painfully characterized by the ongoing weakness that succeeded the 2008 financial crisis in the US, that persists today in Europe, and that threatens to inundate emerging markets.

Given continuing trade imbalances—chiefly the surpluses enjoyed by China and Germany against the respective deficits run by the US and eurozone peripheral nations—experts say devaluation in some currencies is inevitable. The question is whether the changes can be coordinated and limited instead of allowed to turn into a downward spiral. The answer to this depends on whether government austerity is effective or not in getting developed economies onto a sustainable growth path despite continued, weak demand.

THE DEMAND PREDICAMENT

Even after extraordinary amounts of quantitative easing by the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, and even (belatedly) the European Central Bank, that dearth of demand remains. And yet governments are ignoring their other macroeconomic tool—fiscal stimulus (government spending aimed at stimulating the economy)—out of concern, valid or not, that inflation and interest rates would spike as a result, sending capital markets into a tailspin and the real economy down with them.

Without new demand for imports to offset the effect of monetary easing, however, analysts say currency rates in many countries will inevitably fall—given the economy’s current condition. And unless demand increases, either through fiscal stimulus or rising business and consumer confidence—which proponents of austerity say will materialize if policymakers stay the course on cuts—the only alternative to currency devaluation is tariffs or even more stringently deflationary anti-trade measures. The prime example of this would be a return to the gold standard, as the most extreme inflation hawks recommend.

But anti-trade measures would only make matters worse, according to a paper on the Great Depression written in 2009 by economics professors Barry Eichengreen of the University of California at Berkeley and Douglas Irwin of Dartmouth College. “Trade protection in the 1930s was less an instance of special-interest politics run amok than second-best macroeconomic policy management when monetary and fiscal policies were constrained,” the economists wrote.

Others see a similar scenario unfolding today as policymakers take half-measures or worse to deal with the aftershocks of the financial crisis. “Once we decided to take fiscal policy [stimulus] off the table, we were left with monetary policy,” observes Simon Evenett, a professor of international trade at the University of St Gallen in Switzerland. “That has unfortunate knock-on effects. We are left with an awful policy dilemma.” Eichengreen agrees with Evenett. The eurozone’s leaders, he says, “have been doing everything possible to destroy demand for the last three years.”

But economists who favor fiscal stimulus question whether politicians can summon the wisdom and courage to change course and avoid a real currency war. If history is any indicator, such a battle would likely lead to full-blown economic depression. If political leaders fail to take fiscal action to stimulate demand, says Evenett, “we’ll be getting close to the 1930s.”

|

|

Evenett, U. of St Gallen: If leaders don’t take fiscal action to stimulate demand, it will look like the 1930s |

OVERBLOWN CONCERNS?

Some analysts, however, contend that austerity is starting to restore economic health in Europe and the US, and that fears over a true currency war are overblown. Although existing trade imbalances have led to currency “mispricing,” Christian Menegatti, managing director of research for Roubini Global Economics, insists that “it is not obvious that imbalances cannot persist as long as the buildup of debt is sustainable.”

Menegatti says there has been considerable progress on rebalancing, as evidenced by the marked improvement in sovereign bond prices for eurozone periphery nations. Menegatti says this is thanks to austerity—despite the pain involved.

That view is seconded by Laidi of City Index. So long as there is more quantitative easing by central banks, especially on the part of the ECB, and continued cutting of government debt, trade imbalances and their associated currency issues, Laidi says, will take care of themselves.

But he adds that the global economy could be in for a shock unless there is “a lot more cutting.” In the US, in particular, he says, “outright austerity is needed,” or its economy faces a “domestic shock” in the form of spiking interest rates sure to abort an already anemic recovery that saw GDP advance by just 0.1% in last year’s fourth quarter. Yet Laidi is confident that such austerity is on the way: He predicts the Obama administration will embrace at least some of the cuts to government entitlement spending that its Republican opposition has proposed.

END OF DOLLAR SUPREMACY

Some like-minded inflation hawks are less optimistic. In a column for Project Syndicate in late February, Martin Feldstein, a Harvard economics professor and former adviser to US president Ronald Reagan, wrote that he foresaw the end of the dollar’s status as the global reserve currency, given current trends in Washington. “If progress is not made in reducing the projected fiscal imbalances and limiting the growth of bank reserves,” Feldstein wrote, “reduced demand for dollar assets could cause the dollar to fall more rapidly and the interest rate on dollar securities to rise.”

Some observers say the end of the dollar’s reserve status would be a blessing in disguise: It would go a long way toward ending the trade imbalances that, they contend, were the root cause of the global financial crisis and continue to cause economic woe.

Former French president Valéry Giscard D’Estaing once said the dollar’s reserve status afforded the US “exorbitant privilege.” But University of Peking professor Michael Pettis says dollar reserve status is actually an “exorbitant burden,” as it prevents the US from exporting more goods and increasing its savings.

Pettis argues that shifting to a basket of reserve currencies, such as the IMF’s special drawing rights, would be far preferable. Such a shift, he explains, would require countries to hold euros and other currencies as well as dollars in reserve, forcing up savings rates in the US and other nations that run big trade deficits and encouraging consumption in those with big surpluses, such as China and Germany.

The only alternative, Pettis says, is consumption taxes in countries like the US and “reinflation” in those such as Germany, though he is anything but confident that those solutions will come to pass.

|

|

Pettis, University of Peking: I don’t see a thing that suggests the eurozone is in recovery |

CHINA AND GERMANY: SHARP DOWNTURN

Yet without such a fundamental but well-managed rebalancing of trade—as Pettis discusses in his recent book, The Great Rebalancing: Trade, Conflict, and the Perilous Road Ahead for the World Economy —the economist sees little prospect of recovery for the global economy, not to mention the eurozone. Instead, Pettis expects rebalancing to be forced on the world via sharp downturns in Germany and China.

“I don’t see a thing that suggests the eurozone is in recovery,” Pettis said in an interview, notwithstanding the rally in periphery countries’ sovereign bond prices. As for China, Pettis says the country has yet to change its export-oriented course—despite a new, avowedly reformist government—and that, he says, will keep the renminbi artificially low and the economy in a bubble.

Pettis notes that Chinese GDP, after slowing in the first half of 2012, took off again in the second, and that debt surged toward the end of the year. And although some analysts describe the surge in Chinese debt as temporary, Pettis insists it wasn’t “a blip.”

But other analysts, such as Jan Dehn, co-head of research for UK money management firm Ashmore Investment Management, are more optimistic about China’s prospects for transitioning to an economy more balanced between exports and consumption.

Even analysts bullish on China’s ability to rebalance its economy, though, are calling for a global framework to address persistent trade imbalances. Dehn notes that QE has done next to nothing to increase spending, as cautious companies and recapitalized banks sit on their cash. Yet he fears that the phony currency war will turn into a real one once the economies of the US and other deficit countries “heal” through continued deleveraging.

|

|

Dehn, Ashmore Investment Management: QE has done next to nothing to increase spending |

REAL CURRENCY WAR

Dehn says he expects the Fed to “lean against” any resultant spike in interest rates through continued QE. But this could lead to a real currency war, if China and other emerging markets don’t allow their currencies to appreciate by 25% against the euro and dollar, which Dehn says is necessary for balance. “Emerging markets need to take the lead,” says Dehn. But “it isn’t an easy process.”

The latest attempt to establish a global trade framework under the auspices of the World Trade Organization, the so-called Doha round, has been in the works since 2001 and is currently deadlocked. Dehn says he sees little prospect of Doha’s yielding positive results.

Both he and anti-austerity analysts agree that ignoring the policy dilemma reflected by the quasi currency war won’t prevent it from turning real. The G20 finance ministers and central bank governors met in Moscow in February, but little progress was made on furthering Doha. Evenett, who is also a member of the Warwick Commission on the Multilateral Trading System after Doha, says the statement about the prospect for currency devaluation that the G20 issued after the meeting was effectively a decision to “deny it exists.” In subsequent remarks to the European Parliament about fear of a currency war, he observes, ECB president Mario Draghi essentially recommended that everyone “stop talking about it.” But, says Evenett, “that’s not going to stop it.”

A solid recovery would stop it. But what the post-crisis environment has painfully demonstrated, says Evenett, is that “monetary policy is good at eliminating tail risk, but not at delivering growth.” Sustainable growth will take either fiscal stimulus alongside monetary policy, or the business and consumer confidence that most policymakers now appear to believe austerity will sooner or later produce.

GLOBAL CURRENCY MANAGEMENT ON THE RISE

Global currencies have seen more active management since the onset of the financial crisis. While the proportion of IMF members that let their currencies float freely declined between April 30, 2008, and April 30, 2012, from 39.9% to 34.7%, the percentage of those managing their currencies increased. The proportion with hard pegs rose from 12.2% at the end of April 2008 to 13.2% four years later. And while the portion with soft pegs of various kinds ticked down from 39.9% to 39.5%, those with “crawl-like arrangements” climbed from 1.1% to 6.3%.

The IMF notes that “this shift away from soft-peg arrangements to other managed arrangements mirrors what happened at the beginning of the crisis, when many countries abandoned less flexible exchange rate arrangements in response to increased volatility in foreign exchange markets.” The proportion of members employing managed arrangements besides soft pegs rose from 8% to 12.6% during the four-year period.

EXCHANGE RATE ARRANGEMENTS, 2008—2012

(Percent of IMF members as of April 30 each year)