Entry Strategy

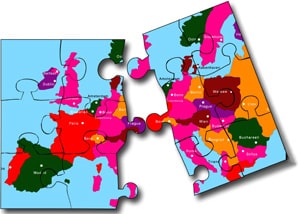

Prospective future entrants to the EU have been watching with interest the progress of the 10 countries that joined the union a year ago.

|

The transformation they experienced did not happen overnight, although as soon as they joined, they gained access to EU structural and regional funds. The benefits of free access to EU markets were already in place beforehand. The largest impact on trade patterns, according to Walter Demel, economist at the Austria-based Raiffeissen Bank, has been a sharp increase in the exchange of goods and services between the new entrants now that remaining barriers have been dismantled. The Czech Republics trade with other accession states leapt by more than 30% last year, whereas previously it had been growing at less than 10% annually, Demel says. Poland and Hungary experienced a similar surge in trade with their neighbors in New Europe.

Most macro-economic or structural change had already taken place prior to accession, however. Each country set out on the process of EU harmonization from its own starting point. Each had its own mountain to climb. And since all of the 10 accession states economies have been steadily integrating over the past 15 years or so, further changes occurring over the past 12 months have been largely the result of continuing momentum.

Going through the accession process meant that the countries involved had already made the effort, says Nicolas Doisy, economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). After that, theres no reason to expect formal entry into the EU to have that strong an impact.

Yet formal accession has made inward investors more confident. Tim Green, partner at private equity group GMT Communications, which specializes in telecom buyouts in the region, with some 25% of deals done in Central Europe, defines these markets as still quite small and relatively immature. That means they also present good investment opportunities for those prepared to accept a higher risk/reward profile. Since we did our first deal in the Czech Republic in 1996, we have seen substantial shifts in attitude, legislationespecially the harmonization of telecom laws to EU standardsand corporate governance issues, he says. Doing business has generally become easier, with less concern over legal ownership and intellectual property rights, all of which makes the markets more attractive to inward investment.

There has also been a substantial change in the quality of local management compared to 10 years ago, says Green. Over the past two years they have begun to look seriously at the financing possibilities of rapidly developing capital markets. For instance, GMT Communications refinancing of Invitel, Hungarys second-largest fixed-line operator, included launching a large tranche of high-yield bonds. It involved considerable structural issues, says Green, as this was only the second time a high-yield bond had been successfully launched in Hungary.

|

Assessing the Benefits |

|

So a year after formal accession to the EU, are the citizens of New Europe experiencing real and tangible benefits? Certainly their economies have been growing much faster than those of Germany or France, which constitute the core of Old Europe. The new entrants have enjoyed year-on-year GDP growth of around 4%, with central and eastern European countries achieving nearly 5% on average in 2004. That is more than twice the growth rates achieved by eurozone countries. Moreover, that has been built on strong exports, with Polish and Czech exports up by nearly a quarter last year in euro terms.

But New Europe still has a long way to go to catch up with its western neighbors in terms of real wages and overall wealth levels. Real labor unit costs are often as little as one third of those in Old Europe, which accounts for the eastward shift of automotive and other labor-intensive industries. However, consumerism is growing more rapidly than the overall economy in most countries, the commercial banks are racing each other to extend consumer credit, andalways an important contributor to the feel-good effectreal estate values have been picking up. If you look at Warsaw, Budapest or Prague, theres a real boom going on in both commercial and residential property values, says Gyuri Karady, partner in the private equity firm Baring Corilius, which specializes in Central and Eastern Europe. But the trickle-down effect to rural regions and smaller towns has yet to occur. The sectors that have benefited the most are those that service the new consumer economy, says Karady. Look at how the big supermarket chains have come in, the sectors where the multinationals are investing and the growth of spend in marketing. Advertising has increased hugely in volume, printing companies are buoyant as the page-count in newspapers and magazines goes up, and Poland has seen a boom in radio stations, he notes. Although the agricultural sectors in the 10 recently joined countries do not enjoy the full benefits of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Doisy points out that they do have access to cohesion and structural funds and money transfers linked to the CAP. Farmers incomes have increased substantially over the past year, he says, although whether New Europes agricultural producers will share the full benefits of the CAP remains to be seen. |

Currency Harmonization

The biggest issue outstanding is when and under what terms these countries will adopt the euro as their currency. Front-runners on this are the smaller Baltic states, with the currencies of Estonia and Lithuania already pegged to the euro. Slovenia also entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II) last June, and Latvia is planning to join in the near future. Apart from having to satisfy the Maastricht criteria on budget deficits, inflation and overall debt levels, these countries have to prove that their currencies can maintain sufficient stability within ERM II bands for two years before being allowed to join the eurozone.

The reason this process started with the smaller states is because of the very prudent way they have managed their economies, says Doisy. Slovakia could follow next year, with the larger countriesPoland, the Czech Republic and Hungarymost likely waiting until at least 2007 to join ERM II.

The main problem for the larger economies is bringing down government spending. Their governments spend more money than they bring in, even though they have relatively high tax levels. They face having to cut current expenditure on deeply entrenched and often highly popular social programs, and that in turn could cause political problems, especially in Poland and Slovakia where elections are coming up.

Doisy believes these countries large fiscal deficits are structural in nature rather than caused by economic fluctuations. To overcome such deficits takes a degree of political will that has not always been evident. Until governments of the Central Europes big three economies get serious about tackling their fiscal deficits, he says, it is hard to see how they can progress toward joining the single currency. Since these countries already have a relatively high tax take as a percentage of GDP, that means cutting down on spending.

Slovakia provides a good example of how to whittle down fiscal deficits. It introduced a flat 19% tax rate for both corporates and individual incomes. In most cases this represented a significant reduction, and, with less tax avoidance and more businesses exiting the black economy, instead of falling, government revenues actually increased. Slovakia also decided not to spend all of the EU structural funds it was entitled to, says Doisy. That helped to keep down its fiscal deficit.

Financing state-funded pensions might prove a more intractable problem, but here the Council of Economic and Financial Ministers in Brussels (Ecofin) has allowed new entrants to exclude pension-related spending from their fiscal accounts. Nonetheless, the process of integrating toward the euronorm is far from over, even for countries that are now within the EU.

|

Prospective Entrants Wait in Line |

|

The relative success of last years EU enlargement should act as a powerful stimulus to those countries still waiting in the wings. Next in line are Bulgaria and Romania, having successfully finalized their membership negotiations last year. Provided they keep their reform process on track, they are scheduled to join the EU in 2007.

The prospect of joining the EU is probably powerful enough to encourage governments to implement the necessary reforms, and now that Romania and Bulgaria have a joining date, foreign investors feel it is safe to go in. Already FDI has picked up, which opens the way for further productivity gains through technology and skills transfers. However, Green argues, They still have further to come in terms of economic stability, access to capital and, above all, quality of management, where they are still a lot further behind. Croatias progress has been delayed by political rather than economic considerations, especially since the EUs recent decision to postpone the start of membership negotiations until it is convinced that the Croatian government is cooperating fully with The Hague tribunal on bringing those suspected of war crimes to justice. However, while it has shown itself ready to wield the stick when it comes to the war-torn states of the former Yugoslavia, Brussels is equally adept at dangling the carrot of eventual EU membership to coax the western Balkan countries along the path of political and economic reform. Macedonia, for instance, filed its formal membership application last year, and Albania hopes to take its first step through finalizing the Stabilization and Association Agreement later this year. That leaves Turkey, which formally began its own journey toward EU membership last December after Brussels finally decided that Turkey satisfied the mainly political Copenhagen Criteria of being a fully functioning democracy with an acceptable human rights record. A longstanding member of NATO, Turkeys inclusion within a broader European Union has been supported by the United States on strategic grounds and because, as a predominantly Muslim democracy, it could form a vital bridge to the Middle East region. Turkey still has a long road to travel to bring its macro-economic and fiscal policies more into line with the EUs norm and in implementing legal and institutional reforms allowing for a freer, more transparent business environment. However, no country that has entered into EU accession talks has ever been refused entry. The experience of previous waves of accession states will provide some useful lessons along the way. Are the new member states of Central and Eastern Europe yet seeing the reward for their efforts? asks Raiffeisens economist Demel. Im inclined to say yes, though the final verdict will only be made in 10 or 20 years time when their citizens have reached comparable income and wealth levels. |

Jonathan Gregson