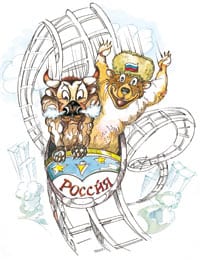

The climate for investment in Russia has cooled since the Kremlin began an offensive on the countrys leading oligarch. But a booming economy is still proving a lure.

Is it still safe to invest in Russia? Maybe, say analysts, but theres little doubt that the background has shifted dramatically since the Kremlins autumn offensive on oil giant Yukos. Make no mistake, the Yukos affair changes things utterly, says Liliya Shevtsova, senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment in Moscow, one of the most highly regarded of the new generation of Kremlin-watchers.Infact, Kremlinologyis back in fashion. Determining the directionthe wind is blowing in the corridors of powerhas becomea must-have skill for domestic and international players alike.

Thatwind suddenly acquired anicy edge in Julywhen Platon Lebedev, a leading shareholder in Yukos, was arrested on charges of tax evasion. The climate became chillier still when Michael Khodorkovsky, Yukoss CEO and a poster boy for the new face of Russian business, was arrested as he was about to board a planeinSiberiaon October 25.

The advent of a new Ice Age was confirmed when parties allied to President Putin won a clear victory in the early Decemberelections for the Duma, the state parliament.Inthe processthey trouncedthetwo economically liberal parties who had been urging Putin to move faster on his program of economic and structural reform.

For Yukos itself, the result has been traumatic. As Global Finance went to press, it seemedthatthe planned tie-up with oil rival Sibneft was off. That deal would have created an $11 billion giant that would have been the fourth-biggest oil company in the world.

Yukoss suddenly dimmed prospects have been reflected in a plunging share price. In mid-December thecompanys stock dipped below $10, a fall of more than a third since the arrestofKhodorkovsky.TheRTS stock market index has tracked Yukoss fall, shedding more than 30 points since its mid-October high of almost 130.

Conventional wisdom is that it was Khodorkovskys well-publicized financial support of three political partiesYabloko, the Union of Right Forces and the former Communiststhat sparked the Kremlin move. Until last year there had been an informal understanding that the privatizations of the 1990s would not be revisited as long as the oligarchs kept out of politics.

The Carnegie Endowments Shevtsova argues that it wasnt just Khodorkovskys funding of anti-Putin politicalparties thatstungthe Kremlin into action. The explicit remaking of Yukos as a transparent,shareholder-focused companythreatened to free the company from the ties that still bind government and politicssomething the more traditionalist elements in the Kremlin couldnt countenance.

Some fear the events of the past few months signal a return to the old days of state control in Russian business life. But its not that simple, analysts say. If some of the ex-security apparatchiks that surround Putin would be happy to renationalize oil and gas, which they view as strategic national resources that by right belong to the state, thats not on the agenda of the president himself. Instead, he seems more interested in frightening the more hubristic oligarchs, breaking down their resistance to paying more taxes.

Tax is the front on which the Kremlin has chosen to wage war. Yukos has cut its tax bill by $5 billion by using tax optimization practices, finance minister Alexei Kudrin has said. And for companies linked with Yukos, the pressure is still on. A week after the Duma elections, tax inspectors raided the St. Petersburg offices of Bank Manatep, part of a group that owns 44% of Yukos. The Interior Ministry said it had opened a criminal investigation into tax avoidance at the bank.

Putin is playing the populist card, though, aware that an increased tax take from Russias booming hydrocarbon industry would help him redistribute some of the benefits in a country where 40 million people are below the official poverty line.

Surveys conducted recently have underscored the popularity of the assault on the oligarchs. In the summer, Russian pollstersRomir-Monitoring found that 88% of all citizens believed the oligarchs riches had been accumulated dishonestly.

While Putins concern for his own political future is clear, the impact on foreign investors of his maneuvering is less easily discerned. Some analysts argue that an enhanced pro-Kremlin majority will actually benefit investors in Russia: Alfa Banks Chris Weaver, for example, says it provides Putin with a platform for further reforms.

And the new atmosphere has yet to frighten off foreign investors. In early December Deutsche Bank confirmed it would go ahead with an earlier plan to buy a 40% stake in United Financial Group, the Moscow-based investment bank. The Russian market is the largest and most important in Eastern Europe, said Kevin Parker, head of global equities at Deutsche Bank.

UK oil giant BP, which sparked a land grab for Russian natural resources when it invested $6.75 billion in oil company TNK earlier this year, has shown no signs of pulling back. The logic that backed that playand that has driven companies such as Chevron to begin negotiations with Russian companiesis still compelling. Abundant quantities of Russian hydrocarbons and Western know-how still make a powerful combination. ExxonMobil and ChevronTexaco may now seek to cut a deal with Sibneft alone, rather than the merged company.

But theres little doubt that companies looking to invest in Russia will have to take stock not just of a chillier domestic climate for investment but more fractious relationships between Russia and Western countries. Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center, a Washington, DC, think-tank, says Khodorkovsky was sorely disappointed when he triedtolobbyAmerican friends for protection against the Kremlin.

Putins reversion to a more authoritarian style has reawakened fears in Washington and beyond over relations with Russia. This fall, bi-partisan legislation was introduced into both houses of the US Congress pushing for the expulsion of Russia from the G8 group of countries. Negotiations for Russia to join the WTO are set to become a lot more difficult. They have already become entangled in a row between the EU and Russia over the countrys subsidized domestic gas market.

Thats also a reflection of just how politicized energy has become. In mid-December the EU and Russia failed to sign an agreement that would have set rules for the transportation of energy across the continents borders. This outcome was largely determined by factors unrelated to the substance of the proposed text of the protocol itself, said Henning Christiansen, chairman of the Energy Charter Secretariat, ringmaster for the negotiations.

With Russia sitting on some of the worlds largest pools of hydrocarbon, and an economy growing by 7% a year, theres little doubt that foreign investors will still want to come to the party. Theres little doubt, too, that they should do their political homework.

Mark Lehane