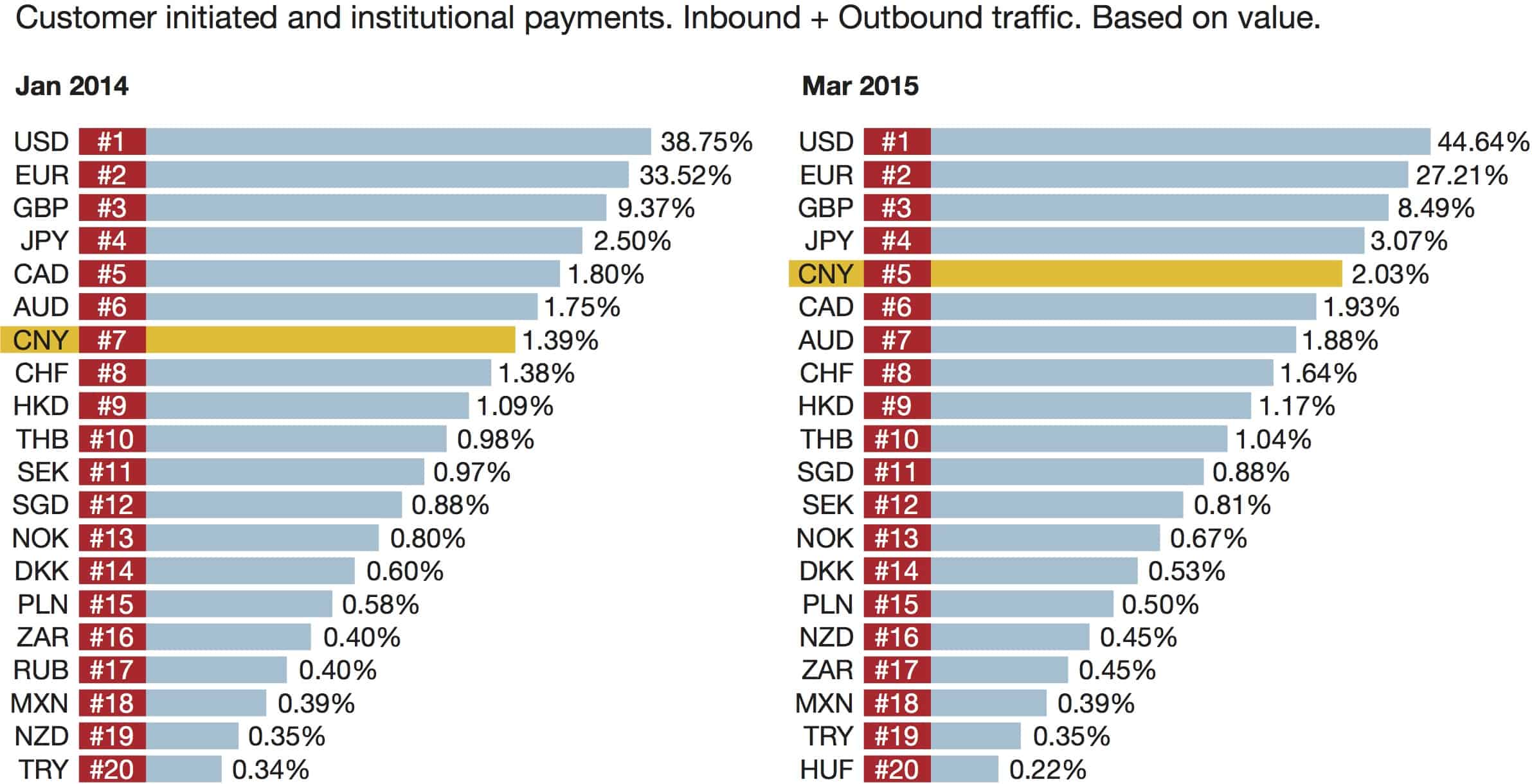

As trade denominated in yuan continues to rise at a phenomenal rate, its significance to global markets is quickly increasing. But even as the IMF considers adding renminbi to the basket of SDR reserve currencies and China’s global political clout rises commensurately, the country has yet to fully liberalize its markets—or its currency.

On many fronts, the renminbi’s relevance to global finance is advancing fast. The pace can seem breathtaking. Offshore transactions are on the rise. Companies with substantial sales in China now use renminbi for offshore acquisitions, to manage global supply chain relationships and to pay employees. ShanghaiHong Kong Stock Connect—a platform linking the two equity markets—opened late last year. In April regulators allowed mutual funds in China to invest via the program into Hong Kong for the first time, sparking a rally in Asian stock markets. China’s financial infrastructure to connect to Asia is being built, and its funding will be partly renminbi-denominated. Plus, the International Monetary Fund is mulling giving the renminbi reserve currency status. Everywhere you look, the renminbi is gaining traction.

But there are still major steps that must be taken by policymakers in Beijing before the currency reaches full convertibility. And when those steps will be taken remains to be seen.

The IMF decision on reserve currency status, if positive, will be a crucial milestone in the international development of the currency, giving the renminbi the cachet to sit beside the US dollar and the euro on the global stage. At issue is the inclusion of the renminbi in the Fund’s “special drawing rights” basket. SDRs form the IMF’s virtual currency, created in 1969 to complement existing reserves of member countries. Granting of SDR status would “send a signal to both corporates and the market that liberalization of the currency has come a long way and build confidence in China’s policy on opening of the capital account,” says Evan Goldstein, Hong Kongbased global head of renminbi solutions at Deutsche Bank.

Goldstein, appointed to this newly created position last year, is among a growing number of renminbi gurus at big banks—another sign of the attention that global financial institutions are paying to the currency’s development. HSBC’s Vina Cheung is global head of renminbi internationalization, a Hong Kongbased job created two years ago. Likewise, Julien Martin heads the renminbi competence center at BNP Paribas, a post created last year. The list goes on. These posts reflect banks’ strategies to consolidate renminbi services into coherent offerings.

The impetus is coming, in part, from clients. “Multinationals are now seeing the importance of staying on top of renminbi developments,” says Cheung. “From a corporate standpoint, they’re already ticking a lot of the boxes. Do they invest offshore in renminbi? Yes. Do they inject funds into China in renminbi? Yes. Do they hedge in renminbi? Yes. They’re looking for a way to establish best practice across all activities—and to stay on top of a fast-moving situation.”

How fast-moving? Carmen Ling, global head of renminbi solutions, corporate and institutional clients at Standard Chartered, likes to point to the growing amount of renminbi cross-border trades outside of China. Ling cites a recent trade from a European company in offshore renminbi—also known as CNH—paying a supplier in Africa. The African supplier was happy to be paid in yuan (yuan renminbi, the denomination), because it could remit funds to its suppliers back in China. These transactions are becoming the bread-and-butter of global financial institutions. “Banks need to play a role in matchmaking these opportunities,” Ling notes.

With internationalization comes responsibility. The acceleration of offshore use of the currency aligns with China’s increasing economic and political clout. The government is seeking inclusion in the SDR basket concurrently with its launch of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). The bank, seen as a rival to the US-dominated World Bank, will finance projects like the building of roads, railways and airports. It will be headquartered in Beijing and start with a pot of $50 billion, with a goal of reaching $100 billion.

So far, 57 nations have signed on as founding members of the fund with China—the US and Japan are conspicuously absent. The move handily addresses a criticism sometimes lobbed at China’s leaders that the government has not stepped onto the stage of world economic leadership at a pace commensurate with its phenomenal growth. The Washington-based IMF is eyeing AIIB developments from the sidelines. Shaun Roache, the IMF resident representative for Hong Kong, reiterated the IMF’s stance at a Hong Kong conference recently, saying that it expects the new development bank will complement rather than compete with the activities of existing multilateral lenders.

If they [the IMF board] think that a review within five years is warranted by changing international monetary arrangements, then that review will be on the table.

~ Shaun Roache, IMF

The AIIB will almost certainly boost the ecosystem of renminbi payments. The creation of the bank is also calculated to edge the IMF toward granting SDR status to the renminbi. When IMF members debate the issue later this year, it will be hard to say no.

One reason is that a review of membership to the SDR basket is done only every five years, making the IMF’s decision particularly delicate. Should it refuse admittance now, where will the renminbi be in five year’s time? China is comfortably in place as the world’s second-largest economy, having edged out Japan in 2010. In terms of purchasing power parity, or PPP, a technique used to determine the relative value of currencies, China surpassed the US to become the world’s biggest economy in October 2014, according to the IMF’s reckoning. Although China’s economy is slowing, the government aims to sustain average annual GDP expansion of 7% over the next five years. This will ensure steady growth in cross-border yuan usage.

Deutsche Bank’s Goldstein refers to the renminbi’s “de jure, versus de facto” status as a reserve currency. Because of China’s status as the world’s biggest trading nation, governments with big exposure to Chinese imports are covering their risk by building renminbi reserves. Jukka Pihlman, managing director and head of central banks and sovereign wealth funds at Standard Chartered, notes, “There are some countries in Africa where 30%, even 40%, of imports are coming from China. So it just makes a perfect risk-management policy, from the asset-liability perspective, to hold renminbi. There are many other reasons why central banks would invest, but that trade linkage is very clear: China is the largest exporter in the world.”

Multinational embrace of the yuan is a given. A recent survey by law firm Allen & Overy asked multinationals outside of China about their projected use of the currency. Some 50% of executive respondents predicted it would double in five years.

The respondents already showed a high rate of adoption of the renminbi across a broad variety of uses. Forty-five percent of the respondents had used it for cross-border intracompany lending over the past 12 months. But only 21% had done so in the 12 months preceding that. Just under 50% said they had channeled renminbi offshore from China without converting to other currencies over the past 12 months, compared with 21% who said they had been doing this for a longer period. About 49% said they were using renminbi to fund acquisitions. Less than 20% said they had been doing so for longer than the past 12 months.

Five years is clearly too long for the IMF to wait. The pace makes it likely the IMF will give the nod this year—but it is not a certainty. The IMF’s Roache says that, in the case of the renminbi’s internationalization, “the board has cut themselves an awful lot of slack. If they think that a review within five years is warranted by changing international monetary arrangements, then that review will be on the table,” he says.

Standard Chartered’s Pihlman concurs but expresses reservations. “There’s been a lot of conversation [among global and multilateral bankers] about the timing. ‘Why don’t we postpone this current review, and arrange another review in one or two years?’ The board does have that leeway. But I think it would be ill-advised.” He points out that the IMF has been promoting the use of the SDR as an alternative to reliance on the US dollar and is in the midst of a program to expand its use by central banks as a reserve currency. “If you now add an additional uncertainty about the timing of the review, that really is hampering the prospects of the SDR itself,” he adds.

Adding the renminbi to the SDR basket now could have an extra benefit for the currency. “Maybe inclusion of the renminbi in the SDR could make the SDR more usable, and at the same time [the IMF could] use this momentum to … help the SDR develop into a more meaningful instrument,” Pihlman says.

Indications are growing that the decision will be positive. The Wall Street Journal reported on May 5 that the IMF is close to making an official reassessment of the renminbi that would declare it a fair-value currency—i.e. not undervalued, as the US and others argue. The new view would help smooth the way to reserve currency status.

JUST A DISTRACTIONIn some ways the focus on the SDR may be distracting from the real issue, which is the pace at which China is opening its capital account. HSBC’s Cheung says the high uptake rate of renminbi for cross-border transactions reflects the fact that the payments side is a first phase—and perhaps the easiest one. Full convertibility would require market openness that is only just evolving in China. Full convertibility—meaning China would completely open its capital account and users would be free to trade the currency cross border with little in the way of barriers—would also require an independent central bank and liberalization of interest rates. China’s bond market—now the third-largest in the world at 35.9 trillion yuan ($5.8 trillion), according to Goldman Sachs—is huge, but corporate issuance is still small. For domestic corporate issues, lack of transparency in corporate reporting can keep lenders away. Panda bonds—foreign corporate issues in the domestic market—have been a dud since they were first touted, with German auto giant Daimler the only non- In contrast, the dim sum—or offshore, yuan-denominated bond—market has grown rapidly since its launch in 2007. But issuance slowed this year as China’s central bank slashed interest rates. Issuance in the first four months of 2015 dropped 52% to 79 billion yuan, according to Thomson Reuters. The sheer attention that liberalization efforts gain in the media belies the currency’s openness. Regulators issued rules allowing cross-border pooling in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone as recently as November 2013. ShanghaiHong Kong Stock Connect is an exciting development, but it took off just this April, when regulators opened the door to southbound investment by mutual funds into Hong Kong stocks. The number of renminbi offshore trading centers has ballooned to 14 in a short time. In 2014, Doha, Frankfurt, London, Luxembourg, Paris, Seoul, Sydney and Toronto joined the club. Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur signed on this year. But outside of the major centers of Hong Kong and Singapore, only Luxembourg and London were named by a sizable percentage of multinational CFOs and treasurers in the Allen & Overy study as attractive locations for offshore renminbi liquidity management over the next five years. Offshore liquidity shortages, in fact, still prevent some corporates from developing renminbi trading relationships. Cheung notes that trade settlement may take only seconds longer in Hong Kong than for a US dollar trade. But to a corporate treasurer, the difference reveals a lack of depth in trading markets even in Hong Kong, the biggest offshore center. Technical hurdles also stand in the way of the currency’s global advancement. The China International Payment System, now under development, will be the global “highway” for yuan transactions. Technical problems forced a delay of its launch in 2014. Reuters has reported that unnamed government officials say the target date is now September of this year. The promise of CIPS is substantial. Cross-border clearing in renminbi currently requires a bank in an offshore trading center or a correspondent bank in China. Post CIPS, trades will be settled with a counterparty in China directly. Then it will be up to corporates to hone their renminbi skills. Both the Allen & Overy survey and a recent HSBC survey found that many corporates see lack of internal familiarity in handling the yuan as slowing companies’ usage of the currency. Bankers, meantime, are adding new corporate renminbi solutions. Deutsche Bank structured an option for China-based milk producer Mengniu Dairy last year—the first-ever non-vanilla, yuan-denominated option to hedge cross-border exposures. With China waiting in the wings for an IMF decision on SDRs, renminbi “noise” is getting louder by the day. Mark Austin, chief executive of industry trade body the Asia Securities Industry & Financial Markets Association, argues that China’s desire to be included in the reserve currency basket will have the residual benefit of prompting the government to keep up its momentum in opening its capital account, in such areas as interest rate liberalization and the creation of new free-trade zones, and in easing restrictions on the use of some financial instruments. “It’s about what China does over the next year to actually accelerate the reforms. Because China seems to want to be included in the SDR basket, and they don’t want to wait five years,” notes Austin. |