Banks have a vital role in supporting the global transition of the economy to net-zero emissions. Banks stress the need for institutional capacity development, along with regulatory and other policy reforms, to support and accelerate climate finance from domestic and external sources, both public and private, for climate resilience in Africa.

The UN-assembled and industry-led Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA) unites a global group of banks currently representing around 40% of global banking assets, committed to aligning their loan and investment portfolios with net zero emissions by 2050.

The Commercial International Bank (CIB) is a founding signatory of the Alliance, with a conviction in the business case of decarbonization. Signatory banks have set immediate targets for 2030 or sooner using science-based guidelines. The NZBA reinforces, accelerates, and supports the implementation of decarbonization strategies, providing an internationally coherent framework.

The Sustainable Banking and Finance Network (SBFN) is a group of financial regulators, central banks, and environmental regulators from emerging markets committed to advancing sustainable finance.

The IFC has the role of strategic and technical advisor. In Africa, the 6 SBFN member countries (Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria and South Africa) have issued green bonds amounting to US$4bn or nearly 100% of all green bond issuance in the region.

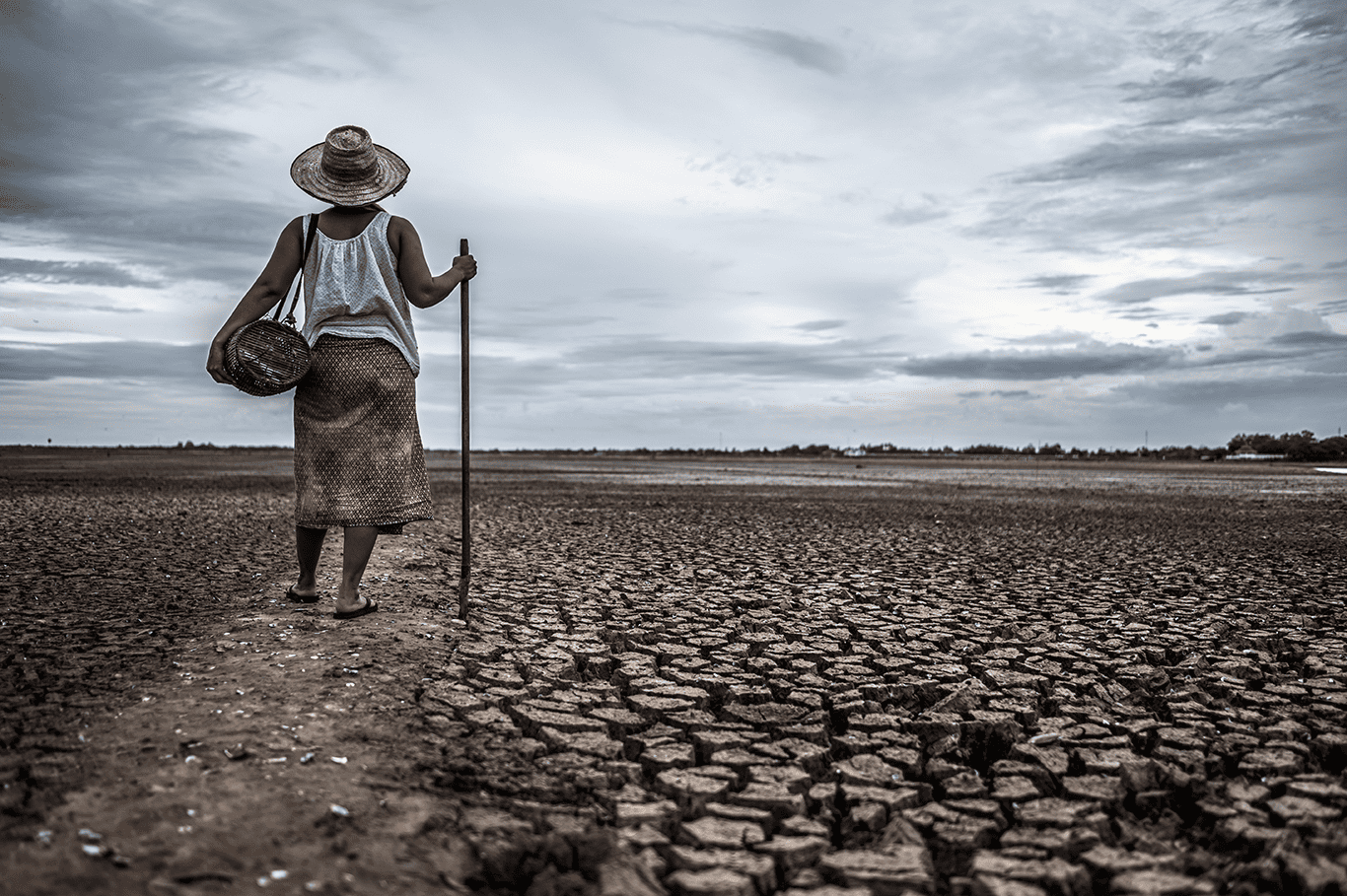

The African Development Bank (ADB) estimates a climate financing gap of around $100bn a year will remain through 2030, undermining Africa’s efforts to support climate resilience. Innovative climate finance instruments can be used to increase domestic climate finance in Africa and bridge the gap.

These instruments include green bonds and loans, sustainability or sustainability-linked bonds and loans, and debt-for-climate swaps. Countries can also mobilize domestic capital through carbon markets. Other innovative climate finance instruments, says ADB, could include realignment of fossil-fuel subsidies and other progressive tax instruments, deployable in key sectors such as energy and transport. Innovative financing instruments and solutions could also include debt swaps, special drawing rights, and voluntary carbon markets.

De-risking tools also need to be developed to facilitate the channeling of financial assets into financial flows for a bolder response to climate change.

Commercial International Bank (CIB), Egypt’s largest private sector bank, successfully issued Egypt’s first private sector green bond for USD100mn, in collaboration with the IFC. The Green bond helped finance climate and environment related projects, targeting energy efficiency, pollution prevention, water management and industrial system efficiency as well as green buildings. Chief Sustainability Officer Dr. Dalia Abdel Kader points out CIB has been focused on engaging its clients to help them realize the business case of sustainable finance.

She added that the experience at CIB has demonstrated the positive risk/return trade off of mitigation and adaptation finance. She added commercial banks in Africa can play a significant role in redressing the disconnection between global investors and investees by helping in ramping up investable projects that meet global investors’ criteria. The supply side of finance is there, Dr Kader says, but we need to work on the demand side by packaging attractive pipeline of African climate projects.

The Islamic Development Bank (IDB) requires member countries to develop relevant strategies and investment plans at different levels, including sectoral and national, to move towards a low carbon and climate resilient development. IDB created a Sustainable Finance Framework (SFF) to enter the Green and Sustainability-linked space and mobilize resources from global capital markets to finance or refinance eligible projects in its member countries.

IDB’s debut Green Sukuk, which raised EUR1bn, was allocated to 11 green projects in alignment with Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation objectives. These included projects for renewable energy, clean transportation, energy efficiency, pollution prevention and control, environmentally sustainable management of natural resources and land use, sustainable water and wastewater management. Its Sustainability Sukuk raised US$1.5bn and targets included SME financing and employment generation. In 2021, the Bank issued its second Sustainability Sukuk of US$2.5bn, its largest Sukuk issuance ever, with 90% of the proceeds deployed towards social projects and 10% to green projects.

On the alternative front, IDB’s Tadamon, a platform for CSOs, has deployed financing and organized crowdfunding for campaigns online related to education, employment, poverty reduction, skills development, and community resilience.

South Africa’s Standard Bank Group (SBG) issued Africa’s largest green bond and arranged innovative sustainable and sustainability-linked funding instruments for clients across Africa. Commitments are dependent on taxonomy standardization. The bank has set emissions reduction targets and portfolio baselines for additional sectors and aims to achieve transition towards net zero carbon emissions from its portfolio of financed emissions by 2050. SBG views gas as a transition fuel in Africa. Development of Africa’s gas reserves will help to balance economic development and social uplift with emissions reduction, by facilitating the switch from higher emitting energy sources to lower carbon fuels.

Banks are helping clients with their ESG scope positions and providing finance, contingent on reaching emission goals. ESG is important, and banks can support clients to decarbonize, connecting finance to compliance with ESG standards. As banks focus finance to companies that meet ESG standards, clients that don’t may need to adjust or pay a higher price for funding. Bank loans are being provided with ESG covenants and emission targets. Most banks consider that the biggest challenge is scope three emissions due to the specific data that should be processed. There is also the issue of how regulators assess certain financing, particularly within the energy or commodity sectors, as banks pursue net zero goals.

Moody’s considers that with the rise of net zero commitments comes the need to increase transparency and accountability to assess whether these commitments translate into action. For banks, meeting their own net zero targets will require a more granular understanding of how portfolio companies will progress towards their individual emissions reduction goals.

Global financial regulators, under the Network for Greening the Financial System, are bringing nature-related risks into their regulation framework. In 2022, the Taskforce on Nature related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) released its framework, outlining how the financial sector might be expected to manage and disclose their actions on nature. As the TNFD promote forward-looking transition risk metrics that meet investor and market demand for transparency, portfolio temperature alignment datasets are growing in popularity.

McKinsey says this presents challenges for African financial institutions due to their current capacity and processes. They say most institutions they work with are building out their climate risk capabilities and have not allocated capacity to take on nature. Many of the banks’ loan portfolios had substantial exposure to sectors with indirect and complex exposure to nature-related risks and opportunities. McKinsey believes that in preparing to address nature-related risks and comply with any future regulation, financial institutions can consider climate and nature from the start and build integrated climate- and nature-related risk assessment and management processes.

Bain believes banks face three main challenges: firming an accurate baseline of emissions in their lending portfolios, understanding whether and when value will emerge during the climate transition, and focusing more on a long-term strategy. Banks that start their transition earlier and focus on this, stand to reap significant profit growth by realizing better economics in their portfolios than banks that hesitate to act, according to Bain. Financed emissions represent around 95% of banks’ overall carbon footprint, way above the effect of emissions from their own operations. To deliver on their commitment, banks will also have to actively engage with and support their customers’ own decarbonization efforts.

Measuring emissions, an essential first step in the climate transition, is challenging. Banks will need to use the emissions data of clients and projects in their portfolios. A successful strategy requires strong measurement, says Bain. For effective measurement and tracking of carbon emissions in portfolios, banks will need reliable methodologies, standards, and tools. Loan portfolios will require constant calibration for both emissions and profitability, and strong governance.

To view the full COP 27 Supplement please click here https://pubs.royle.com/view/global-finance-media-inc/global-finance/november-2022.

Sponsored by: