As the Ukrainian conflict blows up, the GCC economies hit the jackpot.

Since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war, energy prices have skyrocketed and remain exceptionally high. In March, Brent Crude and West Texas Intermediate futures, the two industry benchmarks, traded at their highest prices since 2011, more than $123 a barrel. Refined products are in low supply and in high demand, which has led to fuel and power prices hitting record levels worldwide.

For most countries, the consequences are bitter—slowing post-pandemic recovery and curbing living standards. Some European governments were prompted to introduce new fuel subsidies to avoid widespread protests, while the United States faced a record 9.1% inflation by June.

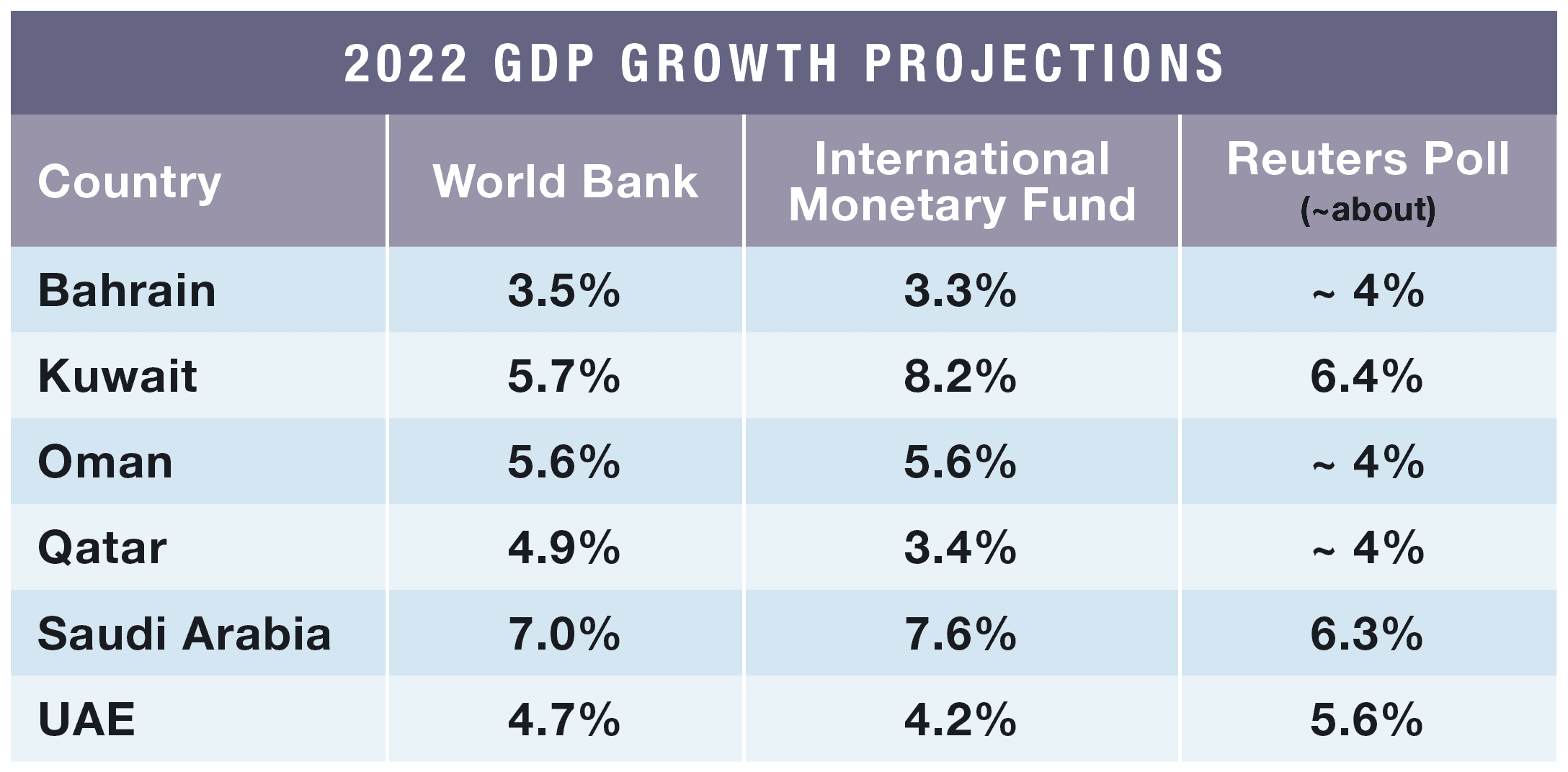

For oil producers, however, it’s payday. In the Middle East, Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries are projected to take in $1.4 trillion in additional revenue in the next five years, according to the International Monetary Fund. Some of the world’s wealthiest nations, Gulf countries are about to enjoy their highest growth in a decade.

“The GCC economy still has 60%-70% of GDP coming from oil, gas or chemicals; so any time energy prices fluctuate, this affects the whole economic situation,” says Bart Cornelissen, partner and Energy, Resources and Industrials leader at global consulting firm Deloitte.

Experts forecast GDP for the GCC will rise 5.9% this year from 3.3% in 2021. “This recovery [is] likely to continue in the medium term, driven by the hydrocarbon and nonhydrocarbon sectors,” notes the World Bank in its latest regional assessment.

“Higher oil prices are supportive of GCC economies,” says Mohamed Damak, senior director of financial services at S&P Global Ratings. “All things being equal, they will result in higher government revenues, providing more room for GCC governments to increase spending.”

Alongside soaring prices, oil-rich countries are also producing more, as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) together with the 10 largest non-OPEC petroleum-exporting countries (OPEC+) gradually lift their pandemic production cuts. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) had a strong start even before the war, respectively increasing output in the first three months of 2022 by 19% and 12% year-over-year. Following US pressure to mitigate the crisis in June, OPEC+ members agreed to further accelerate production by 648,000 barrels daily starting in July, increasing again by the same amount in August.

That production increase is meant to alleviate pressure on prices as the Western countries broaden their sanctions on Russia’s petroleum and natural gas exports. Before the war in Ukraine, the Russian Federation was the world’s top natural gas exporter and second-largest crude exporter, accounting for approximately 17% of gas and about 10% of global crude oil.

GCC Banks Cash In

As economies benefit from post-pandemic pickup and substantially increased hydrocarbon revenues, most GCC banks should see rising profitability and expanding credit growth.

Positive economic indicators have pushed the international rating agency Moody’s to change its outlook in April from negative to stable for the banking sectors of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman, the UAE, Qatar and Bahrain.

“We have changed banking outlooks in the GCC states, as the jump in oil prices is boosting economic activity and economies are recovering after the coronavirus shock,” said Nitish Bhojnagarwala, vice president and senior credit officer at Moody’s, when announcing the changes. “Non-oil activities including tourism will also contribute to the improvement in some areas.”

Thanks to higher oil prices, S&P Global Ratings also expects banks’ operating environment to become more supportive, according to Damak.

“While we still expect to see some inflow of NPLs [nonperforming loans] from the pandemic hangover, we do not expect the NPL ratio to exceed 5%, from around 3.5% at year-end 2021, for the top 45 banks in the region,” he says. “We expect banks’ profitability to improve, thanks to the confluence of lower cost of risk and higher interest rates. Based on the top 45 banks’ disclosure, an increase of interest rate by 100 basis points translates into an increase in the bottom line by 13% on average.”

Although the outlook is positive for Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Oman, Bahrain and Kuwait, international observers see Qatar as more vulnerable due to Qatari banks’ high exposure to external debt. That being said, the country enjoys ample buffers; and new central bank regulations partly relieve those concerns. Moreover, expanded gas facilities, large infrastructure projects and the upcoming FIFA World Cup are expected to bring substantial additional revenues from 2022 onward.“There is a lot more liquidity generally in the GCC, which then cascades down into the wider economy and banks,” says Adnan Fazli, Transaction Services partner and leader in financial advisory at Deloitte. “There is a knock-on impact, and that’s also evidenced by what we’re seeing in the UAE and Saudi capital markets: the stream of IPOs; the desire to monetize both state-owned and family-owned businesses.”

Risks Of Inflation

The downside is, of course, inflation. All over the world, the war in Ukraine has translated into supply chain disruptions and higher food and commodity prices. GCC countries are not immune to that trend.

“There is a lot of money in the region due to the current oil and gas prices, and that is not always helping,” says Deloitte’s Cornelissen.

“It is a double-edged sword; because the GCC wouldn’t benefit from unsustainably high prices at these levels for very long, because it starts feeding back into the macroeconomy and ultimately the consumer,” adds Fazli.

Inflation in the GCC is expected to peak at 3.1% this year after reaching 2.2% in 2021, according to the IMF. Alongside real estate, the GCC’s major weak spot is food prices, as they import nearly 85% of what they consume.

But first, they can afford it; and second, they have learned from previous experiences with shortages. After international food prices spiked in 2008, the UAE and other Gulf states rushed to buy African farmland to secure food supplies; while in 2017, Qatar faced the start of a nearly four-year embargo by its neighbors. Although the desert climate is not ideal for agriculture, GCC countries are investing heavily in new technologies such as aquaponics and vertical farming, to produce locally and reduce their dependency on imported meats, grains, fruits and vegetables.

Invest In Transition

The GCC countries could face a backlash from the higher oil prices as they are putting green transition at the top of the agenda for most hydrocarbon importers. In the long term, industry watchers expect fossil fuels to become obsolete, depriving these countries of their most significant revenue stream.

“The Middle East is filling a good part of the gap that the Europeans are feeling now,” says Deloitte’s Cornelissen. “If you look at a 15- or 20-year time frame, there is an energy transition going on; there is a global reduction of hydrocarbon usage. So, you hope that the extra money in the market is spent wisely—not on consumption but on investment in restructuring the economy and making it less dependent on hydrocarbons.”

For some years, all six GCC countries rolled out massive economic diversification blueprints that entail opening themselves to foreign investment, boosting private sector growth and non-oil activities. Gigantic infrastructure projects are underway all over the Arabian Peninsula, including the $500 billion new city of Neom in Saudi Arabia; the $200 billion being spent on construction ahead of the World Cup in Qatar, most of which is going into improving the transportation system; or on a smaller scale, the UAE’s ambitious solar farms and space program.

“A high oil price can benefit these economies for a period of time,” says Fazli. “They can use that cash to invest in and to initiate programs that otherwise might have had to come through monetization of government assets at lower valuations, or perhaps borrowing.”

For the extra income to benefit future generations, however, local governments will have to resist the temptation of immediate spending.

“In the past, high oil prices reduced the impetus for GCC governments to diversify; it remains to be seen how they will react to the current high oil prices,” warns S&P’s Damak.

How long oil prices will stay up remains unknown.

“Nobody has a crystal ball on that one,” says Cornelissen.

To a large extent, it may depend on the continuation and outcome of the conflict in Ukraine.