Inefficient Brazilian health care system spurs private-sector innovation.

Healthcare has been long overdue for disruption. A lot of countries in Latin America have public overwhelmed and inefficient health systems. In Brazil, for example, public facilities—which make up less than half of the total—are unable to meet most of the demand, according to the Center for Health Market Innovations.

At the same time, only higher-income individuals can afford private insurance, says Hernan Kazah, co-founder and managing director of Kaszek Ventures and co-founder of Latin America’s first ecommerce platform, Mercadolibre.

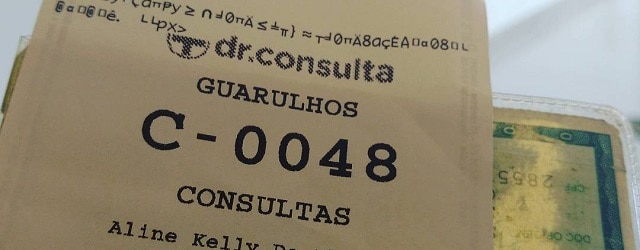

That means that more 100 million Brazilians, roughly half the population, are medically “homeless” and have to wait for up to a year to see a doctor, says Thomaz Srougi, founder and CEO of dr.consulta, a Sao Paulo–based healthcare company that caters to the uninsured by offering same-day consultations for multiple specialities across its 47 local clinics.

The company’s goal is to offer “the best healthcare in the world at the lowest possible cost,” by aligning doctors’ compensation with patient satisfaction and using data to manage business processes. “In Brazil, the whole system is organized around health insurance, not the patient,” Srougi says. “Insurance companies send patients to doctors…and doctors are incentivized to prescribe medications—the more the better—not to provide a service [to the patients].” In contrast, dr.consulta ties doctors’ compensation to their productivity, adherence to medical protocols, and patient satisfaction—and its doctors make as much as five times their private-sector counterparts, according to Srougi.

The company uses technology at every step, from customer acquisition to scheduling and medical records, says Kazah, whose firm is an investor. This data-driven approach has been applied from the start and is now being managed by software developed in-house. Dr.consulta recently developed a patient no-show model and a demand-prediction model, among other tools. The company’s ultimate goal is to become a care coordinator that helps patients by enabling their various doctors to communicate through the software, says Srougi.

Another interesting development in healthcare is the use of new technologies in diagnostics. Mexican start-up Unima, for example, is tapping tech to quickly diagnose contagious diseases without lab equipment. The process involves a test on specially treated paper that can be scanned to a smartphone for diagnosis, says Jose Luis Nuno, Unima’s CEO. Nuno hopes that his start-up will eventually form part of a remote-medicine industry that could allow professionals to monitor patient health via the Internet, augmenting access to diagnostics for 2 billion people in the developing world.

Easy payments via smartphone are exciting developments, to be sure. But visionaries like Srougi and Nuno are innovating in support of what is arguably any country’s most important resource: its citizens’ health.