With uncertainty pushing investors to safe harbors and future policy unpredictable, smaller and weaker markets are likely to see slower growth and diminished investor interest.

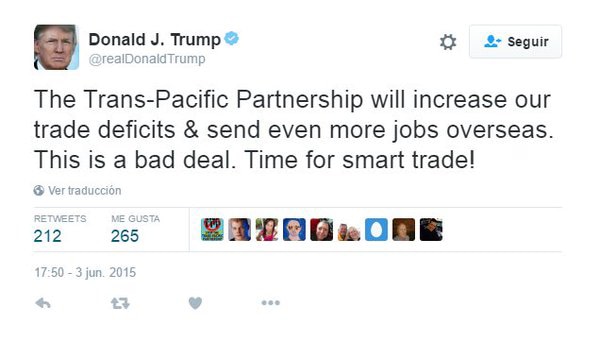

Donald Trump’s US election triumph has profound geopolitical implications. The president elect’s protectionist views on international trade suggest emerging markets will bear the brunt of radical changes in policy—his victory effectively dooms the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) and portends a renegotiation of Nafta (North American Free Trade Agreement). In the ensuing upheaval, China and Mexico look decidedly vulnerable. The Mexican peso fell to record lows against the dollar in the immediate aftermath of the election, capping a volatile period in emerging markets following the attempted coup against Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoan in July. Amid the uncertainty, foreign direct investment (FDI) has faltered.

In its latest analysis, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) said global FDI flows decreased by 5%, to $793 billion, in the first half of 2016, compared to the second half of 2015, but remained above the half-year levels in 2013 and 2014. The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (Unctad) estimates a total decline in FDI of 10% to 15% this year, citing “fragility of the global economy and the persistent weakness of aggregate demand.”

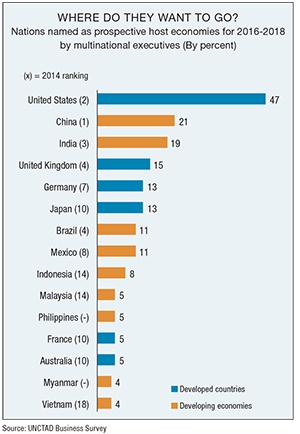

Michael Henderson, an analyst at Verisk Maplecroft, a risk analytics firm, tells Global Finance a reduction in FDI will ripple through emerging markets economies: “Since emerging markets are constrained by a limited pool of domestic savings, a drop in FDI will mean lower investment in productive capacity and weaker GDP growth.” Unctad, in its Global Investment Trends Monitor, published in October, predicts FDI will resume growth in 2017 and exceed $1.8 trillion in 2018—though remaining below the pre-crisis peak. In emerging markets, China and India remain the top investment destinations for multinational enterprises. (See chart).

Asia

In the first five months of 2016, FDI inflows to China amounted to $54.2 billion—4% higher than in the same period of 2015, despite uncertainty about China’s economy. Overall, Unctad expects FDI in Asia to decline by around 15% this year. Cross-border M&A activity in the Asean (Association of South East Asian Nations) region through the first quarter of 2016 was $5 billion—40% of what it was in the same period in 2015, offering scant evidence that the $2.6 trillion Asean Economic Community launched in 2015 is fueling activity. In addition, the number of greenfield projects announced in 2015 was 5% lower than in 2014, says Unctad.

To be sure, the region’s capacious appetite for infrastructure—reportedly $8 trillion, according to the Asian Development Bank—is likely to sustain the interest of multinationals. Yet even there, one of the main funding pillars, the public-private partnership, is mired in confusion over unclear investment structures. Still, countries like the Philippines that are in dire need of improved infrastructure are pushing ahead. Last month the administration of president Rodrigo Duterte announced projects worth an initial 200 billion Philippine pesos ($4.25 billion) to decongest Manila, with future plans to spend as much as 7% of GDP on infrastructure.

Elsewhere, FDI flows to some Asian economies, such as India, Myanmar and Vietnam, are likely to see a moderate increase in inflows in 2016, says Unctad. There is no question that increases in wages have made China comparatively expensive, benefiting neighbors like Vietnam and Myanmar. Myanmar has become an important FDI destination, with greenfield projects totaling $11 billion in 2015, and $2 billion in the first quarter of 2016.

Central/Eastern Europe

With renewed prospects for a thaw in frosty Russia-US relations following Donald Trump’s election victory, the recession that has gripped Russia’s economy may be bottoming out. FDI in Russia slumped in 2014–2015, but large privatization plans announced recently could ignite renewed interest. Russia is being forced into action because of heavily depleted foreign exchange reserves and a current-account deficit stemming from low energy prices and depreciation of the ruble. Rosneft, the largest Russian oil producer, decided to sell 29.9% of its Taas-Yuriakh subsidiary, which operates one of the largest oil and gas fields in eastern Siberia, to a consortium of three Indian companies.

This year the Russian government announced new privatizations of sizable state-owned companies, including 50% of oil firm Bashneft and a 10.9% stake in both the diamond miner Alrosa and VTB Bank, according to Unctad. The rush to privatization in Russia is also likely to spill over into other CIS countries—at the end of 2015, the government of Kazakhstan announced the largest privatization of state-owned companies since the country became independent in 1991. The move could see privatizations in the energy, telecoms, transport and mining sectors. Uzbekistan has also announced plans to privatize 68 major companies in a bid to attract strategic investors. Unctad says the EU integration process and increasing regional cooperation will likely support FDI inflows.

Africa

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) paints a picture of a polarized continent in its updated regional outlook. Countries including Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Kenya and Senegal are forecast to continue to grow at more than 6% a year. Conversely, commodity exporters face severe economic strains and include the region’s three largest countries—Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa—which are expected to grow just 1.5% this year.

Unctad sees FDI into Africa increasing an average of 6%, to $55–$60 billion, this year with a number of greenfield projects already announced. In the first quarter of 2016, their value totaled $29 billion—25% higher than the same period in 2015. The continent’s economic fortunes have been tied to the ebb and flow of commodity prices, but Unctad says countries are reviewing policies to encourage FDI. East Africa, for example, has become a go-to location for light manufacturing. Proximity to major markets in Europe and West Asia is also attracting export-oriented investors from East, South and Southeast Asia.

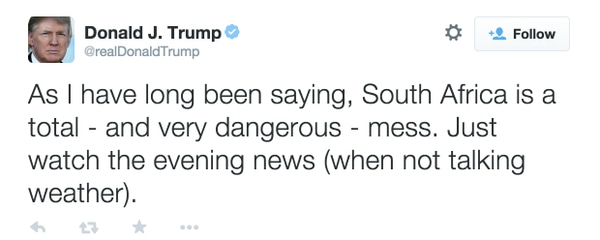

Africa’s lead emerging market, South Africa, is stagnating and has seen its currency fall. Some investors believe euphoria over the continent’s potential is overplayed, yet there are pockets of confidence. There is a buzz around Africa’s auto industry. According to Unctad, PSA Peugeot-Citroën, Renault and Ford have announced investments in Morocco; Volkswagen and BMW, in South Africa; Honda, in Nigeria; Toyota, in Kenya; and Nissan, in Egypt. Capital expenditure by multinationals into the auto industry amounted to $3.1 billion in 2015, Unctad estimates.

State-owned assets could be used to attract foreign capital through privatization. Sonatrach, the state-owned Algerian oil and gas company, has signaled it intends to sell its interests in 20 oil and gas fields in the country. Meanwhile, Egypt’s decision to float the pound, following a near 45% devaluation, could attract investors to Egyptian assets.

Latin America

Brazil has been dogged by political and economic turmoil, but evidence increasingly shows that at least the pace of contraction is easing. Brazil has the second-highest nominal and real interest rates in the emerging markets world (after Ukraine). The picture throughout the region is also mixed—retail spending in Latin America is not growing at all on an annual basis, according to Capital Economics. That patchy performance underlines Unctad’s hawkish outlook for FDI inflows into Latin America and the Caribbean to decline by 10% in 2016, to $140–$160 billion.

Commodities are acting as an economic drag, and the Mexican peso has been battered by uncertainty over the outcome of the US presidential election. The Geneva-based body says the value of greenfield projects dropped 17% from 2014, to $73 billion, led by an 86% decline in the extractive sector in 2015. That also accords with the capital expenditure plans of the region’s major state-owned oil companies—Petrobras (Brazil), Ecopetrol (Colombia) and Pemex (Mexico)—who foresee a sharp reduction in their investment outlays in the medium term.

M&A activity has also declined sharply in the first quarter—and well below the quarterly average in previous years. Yet currency depreciation could spur the acquisitions of assets in the region. Cross-border M&As in the first quarter of 2016 were up sharply—80%—following sales in Brazil, Chile and Colombia. Investors shy from countries with large deficits. “Countries with large external financing requirements are most at risk,” says Verisk Maplecroft’s Henderson. “Fewer incoming dollars could put a brake on imports of essential goods and make it harder to pay foreign creditors.”

The presidency of Donald Trump augurs a period of uncertainty for financial markets until the clouds of campaign rhetoric have cleared. Emerging markets may experience short-term turbulence and will need to increasingly compete for FDI. Balancing risk and reward remains vital, but some analysts believe emerging markets remain attractive. “We feel that emerging markets will perform well,” says Alexis Hombrecher, portfolio manager at emerging markets specialist Whard Stewart. “By the time 2017 rolls along, we expect inflows into emerging markets to continue to pick up and the asset class to perform very well on the whole.”

Still, Mr. Trump will not be inaugurated until January. In the intervening period, speculation over his intentions will be rife and even newly anointed emerging markets in the Middle East are not immune to fickle investors.