We present a rare tour of the newly opened Iranian banking sector. Westerners will be surprised by what they find—in both philosophy and performance—in this long-hidden area of the banking world.

Shut out of global banking for years, Iran holds some mystery, offering surprises and speed bumps for those seeking to establish ties.

In January, the lifting of economic sanctions unlocked billions of dollars worth of Iranian assets and opened the way to re-integrate Iranian banks into the global financial system. Mohammad Nahavandian, president Hassan Rouhani’s chief of staff, hailed “a new environment in the Iranian economy that is positive and welcoming,” to a London audience in February, ending his remarks with: “There is much to gain; let’s engage.”

But anyone expecting Iranian banks to emerge as significant players in the world’s major banking centers in the short-term will be disappointed. While the long-term potential for Iran’s banks—and its economy—is undeniable, both Western and Iranian bankers may be surprised when they start to address the practicalities of rebuilding business relationships that, in some cases, have lain dormant since the Iranian revolution in 1979.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreed between Iran and major Western powers in July 2015 came into effect on January 16 this year. Its key provisions entailed the lifting of most—but not all—of the economic sanctions imposed on Iran. Restrictions on financial transfers with Iran, correspondent relationships with Iranian banks, and establishing offices in Iran are lifted. Sanctions against the Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran are also lifted, and Iran has been allowed to reconnect to the SWIFT payment network. By mid-March, 26 Iranian banks had reconnected to SWIFT.

And while Iranian banks look outward, foreign banks are looking anew at Iran. In February, Belgium’s KBC and Germany’s DZ Bank said publicly that they were handling transactions for Iranian clients. In March, Oman’s Bank Muscat announced that it would be opening an office in Tehran. (Oman has always had close relations with Iran and hosted many of the negotiations that led to the JCPOA.)

However, most large European banks remain extremely hesitant about resuming business with Iran. The reason is simple: The US continues to impose a wide range of sanctions.

Although the US is a party to the JCPOA, most US sanctions against Iran remain in place: The US has lifted only those sanctions related to Iran’s nuclear ambitions. US citizens continue to be prohibited from transacting business with Iranian companies and individuals. There are exceptions—for example in relation to Iran’s civil aviation industry—but these are highly specific. The prohibition on US firms supplying spare parts to Iran’s aging commercial aircraft was a source of great resentment in Iran, since it was seen as deliberately undermining air safety.

Perhaps most importantly, the US continues to prevent international banks from clearing Iran-related transactions through its banking system. As a result, it will continue to be hard, if not impossible, for Iran to conduct trade in US dollars (as dollar-denominated international trade transactions inevitably entail contact with the US banking system). Iran has been able to move its international trade into other currencies, in particular the euro, but since many non-dollar cross trades (transactions with two different non-dollar currencies) are also cleared through the US, this lack of access to the US banking system remains significant.

Despite restrictions, what can intrepid Western bankers expect to find when they start engaging with banks in Iran? They will find a banking system with assets of around $500 billion: smaller than Turkey’s (about $800 billion) and Saudi Arabia’s (about $600 billion), but significantly larger than those of neighbors to the east, such as Pakistan (about $125 billion), and in central Asia. The banking sector comprises 29 banks, of which 19 are majority or wholly privately owned. There are three state-owned commercial banks; five specialized government-owned development banks, and two state-sponsored banks focusing on charitable works.

Private-sector banks account for about two-thirds of loans and deposits in the banking system, with the state-owned commercial banks and the specialised banks dividing the remainder between them. Loans to the private sector account for about 43% of banks’ aggregate assets, according to figures published by the Central Bank of Iran, and they are equivalent to about 80% of private sector deposits. So far, the picture looks quite normal—similar to many emerging markets banking systems.

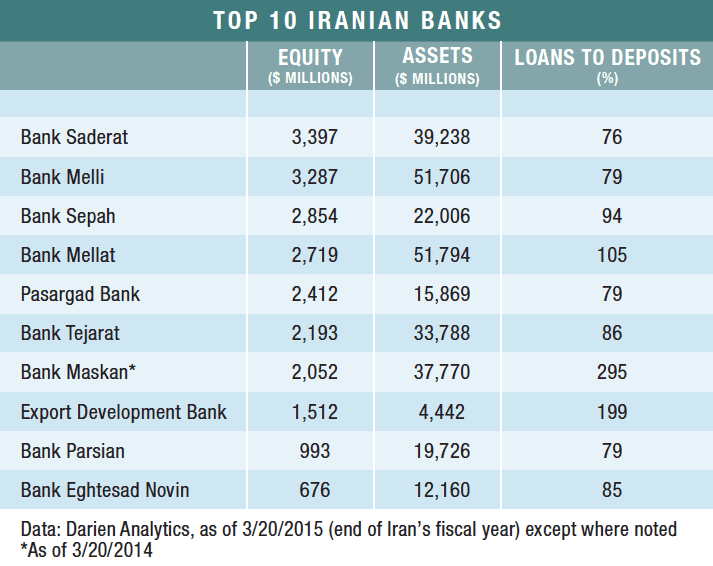

However, one challenge that Iran banks will have as they engage with the international financial system is their size. In March 2015 (Iranian years start on 21 March), the largest Iranian bank by equity size was Bank Saderat, with equity of $3.4 billion. The largest bank by asset size was Bank Mellat, with $51.8 billion. Iranian banks are small by international standards and even by some regional standards: Several banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council and in Turkey have assets in excess of $100 billion.

The Iranian banking system is also heavily concentrated. Four banks account for nearly half of all deposits, private-sector deposits and capital: state-owned Bank Saderat and Bank Melli, and the recently privatized Bank Mellat and partly privatized Tejarat Bank.

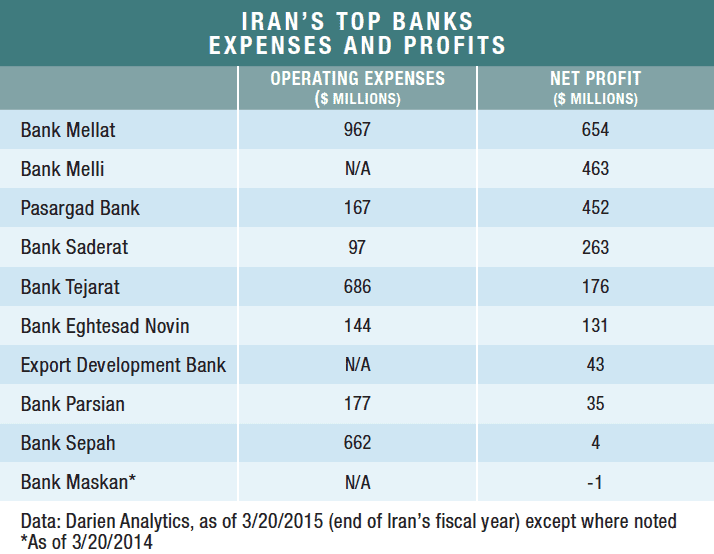

Assessing the financial strength of Iranian banks is difficult. This is partly because their reported figures differ greatly from year to year and prior year numbers are often restated. Volatility in the exchange rate of the Iranian rial accounts for many of these changes. But a more fundamental problem lies in the widespread underreporting of nonperforming loans. It is generally accepted within the Iranian banking community that banks do not fully recognize nonperforming loans and that they under-provision against those that they do recognize.

Perhaps even more important for prospective Western partners, international standards and banking practices are often poorly understood. Implementation of the Basel Accords will be the least of the challenges that Iranian banks will face. Introducing robust controls on money laundering and financial crime—and being able to demonstrate that they are being enforced—will be essential.

Similarly, Iranian banks will have to be transparent about their shareholding structures. Relations with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps remain off-limits even after the lifting of international sanctions, yet the Corps has interests throughout the Iranian economy and its financial system, and those interests are often heavily disguised.

The excitement about the JCPOA and the opportunity it gives for Iran to re-engage with the global economy is entirely justified. Iran has a large and diversified economy, and a large and well-educated population. The desire of Iranian people to follow the direction that the JCPOA is pointing them was clear from the results of the elections held at the end of February, when moderate candidates received far more support than their hard-line rivals. But both Western and Iranian banks have much work to do before normal banking relationships will start to flow.