WHAT SECTORS WILL GAIN?

By Arthur Clennam

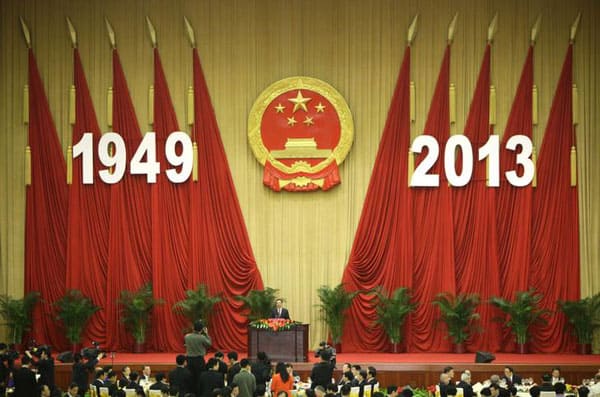

With its new leadership, China is changing. And with transformation comes opportunity.

Reform is Chinas second revolution, said Deng Xiaoping, the father of Chinas modern economy, and the man more responsible than anyone for setting in motion the supreme capitalist state that China seems sure to become in, depending on whom you talk to, 15 to 20 years. Dengs reforms unleashed astonishing growthan experiment with state-guided capitalism on an unprecedented scale in which banks opened the taps for decades to fund unparalleled investment-led growth and a manufacturing marvel.

Now, 30 years from the onset of Chinas second revolution, comes a third. Dengs heirs face a new round of economic restructuring and reform, one that experts believe will be as crucial as the last, and very possibly more delicate to engineer.

These are nerve-wracking times in Beijing. Rebalancing from investment-led growth to an economy based on consumptionaimed at comfortable growth levels well below the high-octane average of the past 20 yearsis the stated goal of the Communist Party of China (CPC). That august body will gather to hammer out a plan for the mechanics of this huge task in a crucial meeting in Novemberthe third plenum, a milestone meeting in a five-year plan traditionally used to announce political and economic reforms.

The Communist Party sees the success of this transition as an existential issue, says Simon Littlewood, president of ACG Global, a consultant to companies in China on working capital management. It no longer can evoke the principles of its founding to ensure legitimacy. Its survival depends on delivering sustainable growth that must lift millions upon millions into the middle class in reasonable time.

Meanwhile, he adds, investment-led growth is not only delivering diminishing returns but cannot be sustained for much longer because of the immense debt in the banking system. These are high-up concerns, but they play into day-to-day company life in the form of tighter money, changing market strategies and legal uncertainty.

Uncertainty is an appropriate word to describe 2013 so far. The year has featured a money market freeze that nearly shut down interbank lending in June; an anti-corruption drive that touched a high point with the life sentence handed down on former Communist Party secretary of Chongqing, Bo Xilai, once considered a leader bound for glory in the nine-member Politburo Standing Committee, the governing body of the CPC that rules China (high-profile probes of other officials are under way); investigations of third-party consultants that have sent shivers through the community of foreign business in China; and slowing growth in the spring that roiled stock markets, followed by a mini-stimulus that is expected to last into November.

In late September, with the backing of the State Council, the nations cabinet, a free-trade zone was announced for Shanghai, bringing a model introduced by Deng himself in Guangzhou many years ago to Chinas supercity. The effort couldalthough there are many skepticsestablish a template not only of trade openness but of investment, administrative and financial reform for the rest of the country.

For business leaders the social calculus can be as daunting as it is for the politicians. How to approach the next 10 years in what remains the worlds single-most-promising market?

Alberto Forchielli, the managing director of Mandarin Capital Partners, a private equity fund based in Italy and Hong Kong, is skeptical that there will be any sudden shifts. The China of today is quite different; theres a lot more talk, Forchielli said. In the past the government went ahead with changes and did not explain a thing. Now, the government tells you what its going to do, but very little gets done.

Thats because theres a greater awareness of the consequences, Forchielli adds: Say you want to open the flow of capital and liberalize interest rates. But thats a very risky thing to do. You can have big swings.

Forchielli believes the mini-stimulus that is quietly being rolled out as lending eases for key industries raises questions about the governments judgment. Going into the third plenum with a steaming economy will not add strength to the argument for reform. In the other words, the government is short-changing itself of politicians universal ploy of blaming a stagnating economy on a previous administration.

But Forchielli agrees with the governments viewChina is slowing and must slow. Therefore investors into China must realign their priorities to benefit from the transition. Whats attractive? Everything related to health and the environment, everything related to product safety will grow, Forchielli says. Luxury goods from overseas will go down. Local fashion and local brands will pick up. E-commerce will overtake traditional retail. In fact, everything is going to be more virtual and more service-oriented and less real. Growth will be seen in soft products and services: computer games, travel expenditures, spas, weddings, well-being and cosmetics.

[READ:

The Next-Gen: The New Stars of China

]

Equally, some hotif volatilegrowth areas of recent years should be shunned. Auto production is tilting toward a crisis, Forchielli says. Likewise, stay away from anything that is in major oversupply, such as construction, housing, anything connected to overbuilding. Dont buy a ceramics company.

As for commodities plays that rely on Chinese demand, such as iron ore and coal mining giants, beware. Its got to come down. Future demand will never be as high as past demand, Forchielli says.

The complexity of the changes in store are illustrated by what the banks are facing. Following the interbank lending freeze in June, Fitch Ratings released a report estimating that total bank credit to GDP stood at 200%a very high figure that exceeds the level in Japan prior to its 1990s economic retreat. More alarming still was the 75% level of recent credit growth over the past four years, unprecedented in a major economy.

CREDIT FLOWS

A number of changes are expected, including interest liberalization that will stop giving an effective subsidy to the banks, which now pay almost nothing for deposits. Artificially low rates translate into a subsidy for banks top clients, as the banks can offer preferential rates while still earning enough on the spread to stay in business. As rate liberalization unfolds, the banks will have to become more competitiveoperationally and in their pricingand will have to claim distinctive niches. State-owned companies cannot expect to survive on the largess of the state-owned banking system.

Attempts to check the flow of credit to state-owned companies has heretofore been managed through unofficial pronouncements to banks to curtail lending across the board, leading to tremendous volatility and insecurity over funding not only of future projects but, in cash-strapped businesses like steel and shipbuilding, working capital needs. But these efforts have backfired. In fact, one of the reasons for the astounding credit growth pegged by Fitch is the proliferation of so-called wealth management products (WMPs), often repackaged dodgy loans that are pushed off-balance-sheet and then traded, but often in highly illiquid markets.

The system of quantitative restrictions on credit, interest- rate ceilings and so on has fostered an environment of financial innovation that is essentially all about regulatory arbitrage, says Mark Williams, head China economist for Capital Economics, a London-based research group. For example, banks cant compete by offering higher deposit rates, so they sell WMPs instead, says Williams. Theres been a surge in this alternative (ie, nonbank) credit. In fact, bank loan growth in August 2013 was the lowest in year-on-year terms since 2006.

The clampdown on this shadow banking market has only just begun. Besides cleaning up this existing mess, rebalancing will foster a new government stance toward investment, Williams believes. Rebalancing involves slowing investment demand such that heavy industry no longer needs the credit, he says. But as they do that, they will presumably also want to stop the same firms tapping alternative forms of finance.

Michael Pettis, professor of economics at Peking University, sees a positive for small and medium-size firms, if theyve maintained robust balance sheets. Most studies show that in a rapidly expanding market, companies take on a lot of debt to increase market share, Pettis says. But in a weak economy, companies without a large debt burden tend to increase at the expense of companies with a lot of debt.

The irony, Pettis points out, is that small and medium-size companiesgenerally seen to be the better-run businesses in the economythat have not had easy access to credit may actually benefit by growing market share as the credit engine slows.

But these companies can expect to be under some strain as the reform process unfolds. ACG Globals Littlewood says, Theres definitely pressure on working capital. Slowing growth and a tight environment for traditional borrowing is putting pressure even on the channels of some cash-rich companies.

Now, Littlewood sees another threat. I work with a lot of businesses whose main customers are precisely the state-owned companies that are the target of credit reduction. That will have a double effect. The state is still a massive part of the economy, so slowing of the state-owned sector means slowing for their businesses, too. Meantime, it will be harder to meet costs for items that will grow anyway, like labor costs.

In this environment, hes telling clients, specialize. Be much more selective where you play. Focus on markets where you can differentiate and retain good margin. Change your operating model and align your costs. Be prepared to let businesses go. It is difficult, of course, to maintain this kind of discipline in any environment, much less one of volatility and change. But to endure and prosper in China will bring ample rewards.