FOREIGN EXCHANGE

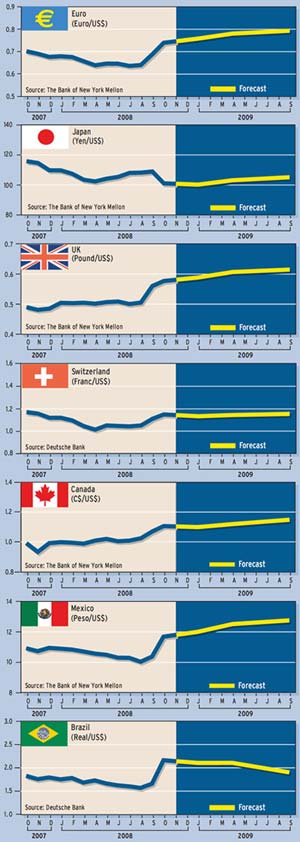

As the financial crisis shook Europe’s banks last month, the European Central Bank joined in a coordinated half-point rate cut with the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England and other central banks, excluding the Bank of Japan. Analysts said the ECB’s shift to an easier monetary policy could herald a series of rate cuts that would go further than any potential additional moves by the Fed.

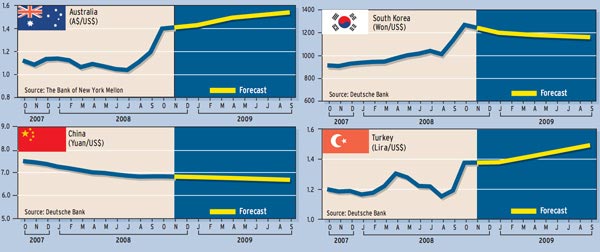

Meanwhile, amid a climate of extreme risk aversion, the dollar and the Japanese yen are benefiting from an unwinding of the carry trade, a strategy whereby hedge funds and other investors borrowed huge amounts of cheap yen to invest in higher-yielding securities outside of Japan. Such investment strategies are now considered to be too risky in a world where credit is tough to get and leverage is working in reverse.

Meanwhile, amid a climate of extreme risk aversion, the dollar and the Japanese yen are benefiting from an unwinding of the carry trade, a strategy whereby hedge funds and other investors borrowed huge amounts of cheap yen to invest in higher-yielding securities outside of Japan. Such investment strategies are now considered to be too risky in a world where credit is tough to get and leverage is working in reverse.

As stock markets around the world fell sharply in early October and financial institutions were being rescued across Europe, global investors rushed to the relative safety of US treasury bonds. The dollar surged to a 14-month high against the euro and a six-month low against the even stronger yen.

“The dollar is being propelled higher, not just by the shifting economic outlook or widening interest rate differentials, or the acute nature of the financial crisis,” says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, based in New York. “Rather, this news is forcing market participants to de-leverage by selling positions that had been financed by shorting the dollar,” he says. Shorting involves selling dollars one does not own, hoping to repay the lender with cheaper greenbacks later.

Commodity prices, including the price of oil, have fallen sharply from their peaks, and the unwinding of positions in commodities also appears to be helping both the dollar and the yen, Chandler says. “Given the pace of the yen’s appreciation on a trade-weighted basis, it risks renewing the deflationary forces in Japan, which have not been convincingly defeated,” he says.

Because the yen’s rise does not reflect either a strong demand to buy Japanese assets or a strong economy, neither intervention nor a rate cut will likely reverse the current trends, according to Chandler. Intervention by the Bank of Japan to stem the yen’s rise would raise all sorts of political issues, and the Japanese central bank is unlikely to pursue such a course unilaterally, he says.

Meanwhile, the passage of the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) into law in the United States failed to alleviate strains in the financial markets, partly because of the increasing worries about financial sector prospects in Europe, according to a report by Barclays Capital Research, based in London. The challenges facing the European financial sector, along with worries that the official responses lack sufficient coordination among member countries of the European Union, are weighing considerably on most European currencies, the report says.

Carl Weinberg, chief economist at High Frequency Economics, based in Valhalla, New York, says the TARP plan could turn a substantial profit for the US taxpayer and will boost the dollar as well. “The TARP is the single most important economic policy initiative of the past 20 years,” he asserts. “It is not perfect, but it is the best deal in town, and it will have positive implications beyond the commercial banking system,” he says.

The TARP empowers the US Treasury to buy troubled assets at heavily discounted prices, well below their long-term economic value, Weinberg says. “No one yet knows what price will be paid for the toxic paper, or what the default rates will be on the underlying mortgages,” he says. “Using conservative assumptions, though, it is easy to see how the taxpayer should make money.”

Over time, people will realize that all the underlying mortgages are not defaulting, and panicky market conditions should abate, according to Weinberg. “We have seen this game before,” he says. “In the 1980s highly indebted economies like Mexico, Brazil, the Philippines and Argentina bought back their own debt from panicked small banks at 20 cents on the dollar.”

The Federal Reserve moved quickly to implement part of the TARP, says Chandler of Brown Brothers Harriman. A key provision that was overshadowed by the size of the package, but that has important implications, is the authority for the Fed to begin paying interest on reserves banks are required to keep at the central bank. “This is important because it will allow the Fed to pump much more liquidity into the banking system without necessarily putting its Fed funds target at risk,” Chandler says.

The dollar’s surge in early October was a classic case of de-leveraging and unwinding of carry trades, says Ashraf Laidi, chief foreign exchange strategist at CMC Markets US, based in New York. “Once again, the dollar comes out on top against all major currencies with the exception of the Japanese yen,” he says.

The fact that the price of gold rose despite the dollar’s rally and the decline in the price of oil reflects credit markets’ anticipation of the global reflationary trend, which could be triggered by the new bout of central bank easing, according to Laidi. “The currency impact of the move could be beneficial for the dollar at the expense of European currencies, on the argument that rate cuts overseas may have more [room] to go,” he says.

Meanwhile, there has been deterioration in current account balances across Latin America, according to a report by emerging market currency strategists at HSBC. Hopes that domestic consumption might plug any gaps left by lower exports have, for the most part, proven unfounded, undermining the decoupling argument, the report says. This means that Latin American currencies will face an uphill struggle in the face of massive portfolio outflows and lower capital inflows, the report explains. Central banks across the region, as well as in Asia, are being increasingly tolerant of currency weakness, insofar as it does not happen in a disorderly fashion, it says.

A beggar-thy-neighbor approach to currency management will become more of a factor as export competitiveness issues become more important, according to HSBC’s emerging market currency analysts.

Gordon Platt