ANNUAL SURVEY: CENTRAL BANKER REPORT CARDS

by Gordon Platt, Antonio Guerrero and Dan Keeler

Central bankers sit tight in the face of renewed global uncertainty.

Indications that the global economic recovery is losing momentum have created a new set of challenges for central bankers, who are being asked to do more in a world drowning in a sea of debt. All of this borrowing could potentially explode in an inflation firestorm or turn into a deflationary death spiral if it saps growth. Neither alternative would be pleasant, nor is either outcome likely if central bankers do their jobs correctly.

Central bankers throughout Asia (excluding Japan) began normalizing policies as soon as the global economy stabilized and showed some signs of recovery in the second half of 2009. Not only did they start mopping up excess liquidity, but they followed with a series of rate increases in 2010. While economic growth in Asia recovered quickly from the global crisis and remains strong, the return to normalcy in interest rates is now being delayed by worries about a slowdown in demand in export destinations in Europe and the US.

While the Fed and the Bank of England acknowledge that there may be a need to increase quantitative easing by pumping more money into the economy, the European Central Bank is putting the focus on austerity. ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet says central bankers need to maintain a credible, medium-term orientation on price stability. This will enable the economic growth that will help to reduce debt, he says.

Meanwhile, US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke is facing dissent within the Fed’s ranks from Thomas Hoenig, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, who warns that by keeping rates too low for too long, policymakers risk repeating the cycle of severe recession and unemployment.

Apart from their roles of conducting monetary policy and operating payment and settlement systems, central banks are also responsible for maintaining the stability of the financial system. They have succeeded in bringing the system back from the brink and are studying ways to prevent and defang future crises. Central bankers are also struggling with the issues of currency exchange rates and speculative cross-border flows. As they face new and difficult challenges, we commend those central bankers who have performed well in the past 12 months and highlight the shortcomings of those who need to improve.

THE AMERICAS

Argentina

Mercedes Marcó del Pont

GRADE: D

Argentina’s central bank has long been criticized for its lack of independence. In recent years, though, it looked like the bank would shake off the shackles of government intervention. Those hopes were dashed after a high-profile battle between former central bank governor Martín Redrado and president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, with the latter attempting to strong-arm Redrado into forking over $6.6 billion in reserves to pay bonds falling due this year. When he refused, Redrado was effectively fired, and the president appointed Mercedes Marcó del Pont to do her bidding. The Yale-educated economist handed over the reserves, as the president had ordered. Marcó del Pont, who Kirchner had earlier appointed to head the Banco de la Nación state-owned commercial bank, is an anti–market activist who supports increased government intervention in the nation’s economy. While economists recommended that Argentina tighten monetary policy to prompt sustainable growth and curb an inflation rate of more than 20%, Marcó del Pont instead loosened the 2010 money supply growth target to 29.4% from 18.9%. With Marcó del Pont’s term slated to end in late September, there was speculation as to whether or not her mandate would be extended. Those hoping that Argentina’s central bank will revert to a more sustainable strategy can only hope it isn’t.

Brazil

Henrique Campos de Meirelles

Grade: B+

When Henrique Campos de Meirelles decided to remain at the helm of Brazil’s central bank this year, market players breathed a sigh of relief. Meirelles, the country’s longest-serving central bank governor, had toyed with the idea of running for the governorship of his native state of Goiás. To do so, he would have had to step down earlier this year, thus forcing Brazil’s president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to choose a successor. Meirelles, a former president of FleetBoston’s corporate and global bank, had left a congressional seat to head the central bank in 2003, once again putting his political aspirations on hold. Yet his tenure at the bank has gained him international recognition for helping to spark one of Latin America’s strongest economic recoveries. Following a 0.2% contraction last year, Meirelles predicts Brazil’s GDP will grow by 7.3% this year, which would mark the country’s strongest growth rate in more than two decades. First-half GDP grew by a record 8.9%, which was one of the world’s highest economic growth rates for the period. Meirelles’ job has been to adjust interest rates and inflation targets to keep the economy from overheating. The central bank has set this year’s inflation target at 4.5%.

Canada

Mark Carney

Grade: B+

Canada’s economy has climbed back to its pre-recession peak, thanks to continued fiscal and monetary stimulus and a modest recovery in the global economy. Central bank governor Mark Carney is concerned, however, that a slowdown in the US economy could become a headwind and that private demand around the world may be insufficient to sustain the global recovery. Despite these concerns, the Bank of Canada raised its overnight rate by a quarter point on June 1 and another quarter point on July 20. Carney says these decisions still leave considerable monetary stimulus in place and that any further reduction of this stimulus would have to be weighed carefully against future developments in the domestic and global economies. Canada’s export-oriented economy and its abundant natural resources mean that it will benefit significantly from a global recovery. Of course, it will also be vulnerable to a global economic slowdown. Canada was the first member of the Group of 7 leading economic powers to raise rates and to normalize monetary policy. It remains to be seen if the move was uncommonly canny or premature.

Chile

José De Gregorio

Grade: B

The earthquake that hit Chile in February, causing more than 500 deaths and some $30 billion in damages, prompted concerns that the nation’s economy, one of Latin America’s most stable, would face difficulties in emerging from a 2009 recession. However, central bank governor José De Gregorio’s policies have helped spark a recovery. GDP grew 6.5% year-on-year during the second quarter and is expected to top 5% for full-year 2010. De Gregorio, a former economy minister who holds a PhD in economics from MIT, has resisted exporters’ calls for central bank intervention to weaken the peso. The central bank chief says the peso’s free float has contributed to economic recovery. After cutting the benchmark interest rate by 775 basis points to a record low 0.5% in 2009, De Gregorio is now systematically withdrawing the monetary stimulus and says market expectations are for the rate to hit 5%-6% in mid-2012. The central bank approved a rate hike to 2% in August. De Gregorio is keeping a close eye on capital inflows as investors flock to emerging markets, saying he is monitoring the situation for its potential implications for monetary policy. The administration still has economic challenges ahead, including tackling unemployment of more than 9%.

Mexico

Agustín Carstens

Grade: B

With Mexico’s economy battered by a combination of ongoing US economic sluggishness (80% of Mexican exports go to the US) and increased drug-related violence at home, the Felipe Calderón administration must perform a balancing act to foster growth while maintaining prudent policies. Calderón put Agustín Carstens, one of the country’s most prominent economists, on the job in January, replacing 12-year veteran Guillermo Ortiz. Carstens, an economist from the University of Chicago, is a former finance minister, central bank treasurer and IMF deputy managing director. The new central bank chief is credited with taking some bold moves in the past, as when he hedged Mexico’s oil earnings for 2009 against potential price declines, allowing the country to pocket an additional $8 billion in earnings as prices fell. Carstens has said drug violence, which has surged in recent years and prompted the Pentagon to issue a warning that Mexico could become a “failed state,” is shaving off a percentage point from Mexico’s economic growth and boosting company operating costs by as much as 10%. Carstens predicts GDP growth could slow to 3.5%-3.7% next year, after this year’s expected 4%-5% expansion. He predicts inflation will drop below this year’s 5% target.

United States

Ben Bernanke

Grade: C

The Federal Reserve’s main job is to keep the economy healthy, and it is far from robust at the moment. Fed chairman Ben Bernanke says the Fed has all the tools it needs to help support economic activity and guard against inflation, although central bankers alone cannot solve the world’s economic problems. With inflation weak, it should be easy for Bernanke to make the choice between boosting employment and keeping prices under control. To his credit, the Fed has embarked on a new experiment that could make monetary policy more transparent and potentially more effective. Fed policymakers will henceforth concentrate on the level of the central bank’s balance sheet. If the level rises, that means the Fed is easing; if it falls, policy is firming. The Fed might lose control over interest rates with such an approach, but hewing boldly to the balance sheet might be just what the current economic situation requires. With businesses reluctant to hire and banks loath to lend, the Fed needs to get the economic juices flowing again by pumping money into the real economy. It could stop paying interest on reserves to encourage banks to lend. As a student of the Depression, Bernanke is unlikely to make the mistake of tightening too soon. He might, however, leave the patient in limbo between vegetation and recovery. With all of the resources at his disposal, Bernanke should do more.

EUROPE

Czech Republic

Miroslav Singer

Grade: Too early to say

A casual glance at the activity of the Czech central bank early this year would have given the impression that the country was peacefully paddling in the calm ocean of a stable global economy. Not having touched the key lending rate for months, Zdenek Tuma, the then-central banker, nudged it down a quarter-point in December, to a historic low of 1%, and confidently predicted that it would not have to budge for some time—perhaps until the end of this year. In May, however, and with no great fanfare, the central bank ate its words and inched the key rate down another quarter-point, admitting that the country’s economy was only barely emerging from recession. It was also becoming apparent that if growth did materialize over the coming year, it would be sluggish at best. Meanwhile, unemployment was rising, inflation remaining stubbornly below-target, and the koruna strengthening enough to present concerns to exporters. Since then, stronger-than-expected growth in Germany, one of the Czech Republic’s main trading partners, has helped boost anticipated GDP growth, but the central bank, under newly installed governor Miroslav Singer, is still expecting the recovery to be painfully slow. With interest rates at historic lows and an economy that is heavily affected by external factors, there is, unfortunately, very little the new central banker can do about that.

EUROPEAN UNION

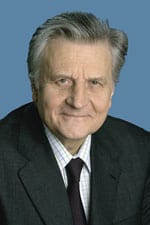

Jean-Claude Trichet

Grade: A

To say that Jean-Claude Trichet has had a difficult year would be a colossal understatement. Europe’s central banker has always had a tough job balancing the needs of a large and diverse economy with the demands of the eurozone’s political leaders, but recent times have been particularly trying. Tensions within Europe have been running high in the wake of the global financial crisis, the aftermath of which has highlighted some of the deep structural problems that at times threaten the stability of the economic union. At the height of the Greek crisis, the very existence of the euro was coming into question, but Trichet somehow managed to avoid getting drawn into the fray, calmly executing his monetary policy decisions while tuning out the constant cacophony of pleas, instructions, complaints and criticisms. His steadfastness has been rewarded: The turmoil over Greece has subsided, and the demise of the euro averted. The scaremongers have moved on to focus on the possibility that Europe might face a double-dip recession, a suggestion that Trichet has repeatedly dismissed. Trichet has held Europe’s key interest rate steady at 1% since May 2009. With growth returning and other key indicators turning positive, doing nothing seems to have been the right strategy.

Hungary

András Simor

Grade: C

Facing a change of government is always a trial for a central banker. Since assuming power earlier this year, though, Hungary’s new center-right government has made life unusually difficult for the country’s central banker, András Simor. As well as cutting his pay by 75% and calling for a criminal investigation into Simor’s investing past, the new leaders have all but blamed his interest rate policies for the country’s economic woes. The latter charge may have some merit, however, as the central bank has kept its key policy rate at a region-wide high of 5.25%—unchanged since April, which, perhaps coincidentally, is the when the Simor’s new political masters took control. Meanwhile, Hungary remains mired in a sour economic stew whose ingredients include declining GDP, rising unemployment, a decidedly wobbly currency and above-target inflation. Simor is refusing to be drawn into a public spat, but the politicians’ attacks on him are taking a toll on investors’ confidence in Hungary—a development that could prove extremely damaging in the long run. Although he may consider the attacks a mere distraction, Simor, by refusing to face off against his detractors, is failing to demonstrate the independence and fortitude necessary for a successful central banker.

Norway

Svein Gjedrem

Grade: B

Perhaps stung by criticism that he acted too slowly in the face of the global economic slowdown early last year, Norway’s central banker, Svein Gjedrem, became the first Western European central banker to raise interest rates in the wake of the financial crisis. In November he surprised many analysts by pushing rates up from 1.25% to 1.5%, explaining in the Norwegian central bank’s characteristically guileless way that inflation was higher, unemployment lower and economic growth more rapid than he’d expected. Continuing a tradition of openness that for many years set Norway’s central bank apart from its predominantly more opaque peers, he predicted a steady, slow rise in rates for the foreseeable future. Sure enough, with inflation approaching 2.5% in December, Gjedrem bumped up the rate to 1.75%. In May this year, while noting that inflation had dutifully popped back down to its 2% target, he pushed the key rate up again to 2%. While he has cautioned that threats to economic growth in Europe might have a negative impact on Norway’s economy, Gjedrem has also made it clear his finger is hovering over the rate-rise trigger, most recently commenting that “future financial imbalances” may prompt him to adjust rates to “a more normal level.”

Poland

Marek Belka

Grade: Too early to say

Hastily installed after the tragic death of Poland’s former central banker Slawomir Skrzypek in a plane crash in April, Marek Belka had big shoes to fill. His predecessor helped ensure Poland was the only European Union member to avoid an economic contraction in 2009 by cutting interest rates, even in the face of rising inflation. Skrzypek’s confidence in his own judgment—and the fact that he got the call right—put him among the top echelon of European central bankers. Belka, a former prime minster and finance minister of Poland and a former director of the IMF, hasn’t had to do too much since taking office, as the country’s economy was already on a stable footing. Interest rates have not changed since Skrzypek hauled them down to a record low 3.5% in June 2009, but despite the relatively loose monetary policy, inflation remains under control. It recently dipped below its 2.5% target and, as the bank predicted, is showing no signs of bouncing back. With the stimulus of the low interest rates, Poland’s economic growth is slowly accelerating and is expected to reach 3% by the end of this year. With solid growth, falling unemployment and benign inflation, it seems likely that Belka will be able to sit on his hands for some time to come.

Russia

Sergei M. Ignatiev

Grade: B

Russia’s reclusive central banker, Sergei M. Ignatiev, has long ploughed a different furrow than his peers in former Soviet Union countries further west, and his attitude this past year has, in many ways, been no different. While Russia’s neighbors were taking giant bites out of their base rates or maintaining them at record lows to counter the effects of the global slowdown, Ignatiev only nibbled away. Perhaps anxious that the ruble might continue its precipitous fall, which was triggered by a stampede of hot-money investors heading for safety in the wake of the credit crunch—and wary that Russia’s hefty post-financial-crisis stimulus program might cause a surge in inflation—Ignatiev didn’t even start cutting rates until Spring 2009. Despite his softly-softly approach, however, his steady reduction of the bank’s key interest rate since then has brought it into record-low territory. At the same time, inflation has eased to what is for Russia a relatively low 5% to 6%, while economic growth has picked up to a healthy 4%, and the ruble appears to have stabilized. Ignatiev isn’t out of the woods, though, as he still has to help deal with a fragile banking sector, a corporate sector that is starved of capital and an economy that still depends heavily on governmental stimulus.

Sweden

Stefan Ingves

Grade: B

After enduring a rough ride through 2008 and 2009, Sweden’s central banker Stefan Ingves seems now to be regaining some of his habitual composure. The former A-grade central banker had a miserable time as the shockwaves from the global economic and financial turmoil buffeted his country’s economy, leaving him looking flat-footed and reactive—a far cry from the days when he would confidently predict both inflation and interest rates up to three years in the future. Undoubtedly chastened by watching Sweden’s economy slump from a healthy 4% growth rate in 2007 to a grim near-9% contraction in 2009, Ingves has taken a cautious approach to monetary policy over the past year. With signs of life returning to the economy—the bank is predicting a beefy 4% increase in GDP this year—and a simultaneous revival in the threat of inflation, the central bank has tentatively pushed interest rates back up from 0.25% to 0.75%. In a sign of its confidence in the resilience of the economic recovery, the Riksbank is winding down such stimulus measures as fixed-interest loans to the country’s banks. It is also, however, accepting the likelihood that consumer price inflation will overshoot the bank’s 2% target in the medium term. Given the turmoil the country has endured for the past three years, that seems a fair price to pay for the promise of a robust economic recovery.

Switzerland

Philipp Hildebrand

Grade: B-

In a long-mooted and smooth transition, Philipp Hildebrand took over from the successful Jean-Pierre Roth as Switzerland’s central banker at the start of this year. Although Roth had done a creditable job of defending his country’s economy from the turmoil roiling the global markets, 2009 saw Switzerland suffer both a 1.5% economic contraction and a 0.5% deflation rate. With interest rates practically at zero, the central bank had little room left for maneuver and was essentially relying on external factors—and its expansionary monetary policies—to come to the rescue. An avowed foe of deflation, Hildebrand has made it clear he will do whatever it takes to maintain price stability, although quite what that would entail, given the circumstances, is not entirely clear. Nine months into the job, he hasn’t had to do anything, as deflation has yielded to very mild inflation and the economy is showing signs of returning to growth. Recently, in fact, the central bank has revealed that it is expecting GDP growth to reach a hearty—for Switzerland—2% this year. Although it’s hard to grade a banker who has barely touched the levers of monetary control in the first nine months of his tenure, Hildebrand’s ability to resist the temptation to tweak for tweaking’s sake earns him a B-.

Turkey

Durmus Yilmaz

Grade: A

For many market watchers, perhaps one of the biggest surprises of the past three years has been the resilience of Turkey’s economy—and its financial system—in the face of unprecedented global upheaval. Turkey’s central bank, under governor Durmus Yilmaz, deserves much of the credit for that resilience. Through skillful management of not just interest rates but reserve requirements, foreign exchange reserves and other liquidity-related tools, the central bank has maintained monetary stability in a country that historically has been among the most volatile. Many investors may still perceive Turkey as a risky place to be, but, as Yilmaz recently pointed out with justifiable pride, “Turkey was one of the few emerging market economies that ended up with a higher credit rating than its pre-crisis level.” Although at the beginning of his term he appeared somewhat tentative in his handling of monetary policy, Yilmaz has displayed a remarkable level of confidence since the onset of the global crisis. His aggressive and early action to counter the downturn in 2008–2009 helped his country sidestep the worst of the crisis, and his measured and transparent approach to unwinding the central bank’s expansionist monetary policies have helped maintain confidence—at home and abroad—in Turkey’s economy.

United Kingdom

Mervyn King

Grade: B

The Bank of England appears to be in a holding pattern. Under governor Mervyn King it has held rates steady at a meager 0.5% since March last year. At the same time, King has been resisting pressure to reduce the level of quantitative easing. Over the course of last year, in fact, he gradually increased the value of the central bank’s asset repurchase program to a hefty £200 billion ($309 billion) and has doggedly defended it at that level ever since. Some observers have expressed alarm that the bank is still, in King’s words, keeping its “foot firmly on the accelerator” when the UK economy is already experiencing sharp GDP growth and above-target inflation. King, however, appears confident that the UK government’s abrupt fiscal tightening will offset his loose monetary policy. There is also some confusion over the impact of King’s monetary policy on the UK economy. Recent signs have been fairly positive, but King himself has warned that bank lending—or more accurately, the lack of it—is constraining the country’s economic prospects. King has watched with evident dismay the struggles of Britain’s small-business sector as companies have found it harder and harder to access the credit they rely on to run their businesses. But in common with many central bankers around the world, King has found there is little he can do to prompt banks to lend if what they really want to do is hoard their assets.

ASIA

Australia

Glenn Stevens

Grade: A

Glenn Stevens, governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, polished his reputation as an inflation fighter with six interest rate increases from October 2009 to May 2010. This was the most aggressive round of rate increases by any member of the Group of 20, bringing the official rate to 4.5% from 3%. The monetary policy tightening was designed to dampen the inflation threat from Australia’s mining boom. It also subdued both consumer demand and the housing market. The country’s unemployment rate is edging up, but it remains about half the US jobless rate. Australia’s economy continues to benefit from China’s strong demand for minerals and other commodities. Meanwhile, wage growth slowed in the second quarter, enabling the central bank to pause in its policy tightening. Interest rates are now near their average levels of the past decade. With economic growth likely to be near trend and inflation close to target this year, Stevens can afford to rest on his laurels.

China

Zhou Xiaochuan

Grade: C

Chinese Fed-speak involves subtle shades of meaning. A year ago the People’s Bank of China said it would use dynamic fine-tuning, as it went from aggressive easing to an appropriately loose monetary policy. Earlier this year, China tightened real estate financing by requiring property developers to submit borrowing plans for review, attempting to head off a real estate bubble while maintaining an easy monetary policy. More recently, the People’s Bank has said it would maintain its moderately loose policy and enhance financial supports to boost the economy’s sustainable development. The central bank is trying to control inflation without using the word “tightening” for fear of triggering a panic and stock market crash. While it vowed to improve the currency exchange-rate mechanism, the stickiness of the renminbi to the dollar means that China lacks a truly independent monetary policy. The country’s fast-growing economy continues to draw speculative investment flows from abroad, stoking the fires of inflation. China abandoned the dollar peg on June 19, but the subsequent rise in the value of its currency has been small, to say the least. This leaves the central bank with the job of mopping up excess funds with weekly auctions of bills. It has also raised reserve requirements to slow the growth of loans.

India

Duvvuri Subbarao

Grade: C

India offers an example of what can happen to an economy if the central bank waits too long to act against rising prices. Inflation accelerated last year after the worst drought in 37 years drove up food prices. Consumer prices are now rising at close to a 14% annual rate, and the Reserve Bank of India is struggling to manage inflationary expectations. New Delhi has allowed state-owned refiners to raise fuel prices, adding to inflation as the government tries to cut subsidies and narrow the budget deficit. “Now, as inflation gets more generalized and demand-side pressures build up, there is a need for monetary policy action,” central bank governor Duvvuri Subbarao told reporters in August. The Reserve Bank, which normally reviews monetary policy on a quarterly basis, surprised the markets twice this year with between-meetings rate hikes. Subbarao says the bank will now hold mid-quarter reviews, and more rate increases are expected if consumer demand fans inflation. The RBI has increased its short-term lending rate four times since mid-March, and commercial banks have begun raising lending and deposit rates. Market liquidity has dried up, but so far economic growth has not been affected.

Indonesia

Darmin Nasution

Grade: D

Indonesia’s House of Representatives elected Darmin Nasution as the new governor of Bank Indonesia in July. Nasution has served as acting governor since May 2009. The central bank’s strategy is to keep interest rates low as long as possible to stimulate economic growth, which is nearing 6%. Bank Indonesia has kept its policy rate at a record low 6.5% all year. Nasution says the bank is not in a tightening mode, despite recent data indicating that inflation is heating up. As one of his first official acts, the new central bank governor plans to issue regulations directing commercial banks to lower their lending rates. Loan growth in the first half of this year was at an annual rate of nearly 19%. Nasution also would like to lop some zeros off the rupiah’s denomination, although he hasn’t decided how many. The House attached some conditions to Nasution’s election. He has agreed to resign if he is ultimately found guilty of wrongdoing in the controversial bailout of Bank Century at the height of the financial crisis. Nasution has also agreed to institute a system of good corporate governance at the central bank. In addition, he needs to come up with a plan to deal with an inflow of speculative foreign capital that is creating a stock market bubble.

Japan

Masaaki Shirakawa

Grade: C

Technically, Japan’s central bank has made all the right moves, but its policies remain ineffective because the country’s fundamental problems are fiscal and demographic rather than monetary. With a huge debt overhang and aging consumers who aren’t spending a lot of money, monetary ease is not having the desired effect of stimulating the economy. Meanwhile, the soaring yen is sapping the strength of the country’s exporters. So why doesn’t the central bank do more to get the animal spirits excited? It doesn’t have to worry about inflation, that’s for sure; and the country can ill afford another lost decade. The Bank of Japan should put its pedal to the metal until the economy starts rolling again. It could even think of approaching the speed limit until inflation hits double digits. In March, the central bank increased a loan program for banks, but demand for credit is lacking. In late August it expanded the program. The country is caught in a liquidity trap, and the central bank has done little to inspire confidence by publicly admitting that it lacks the tools to defeat deflation.

Malaysia

Zeti Akhtar Aziz

Grade: A

Bank Negara Malaysia was the first central bank in Asia to raise interest rates this year, with its first increase in four years in March, followed by additional increases in May and June, bringing the central bank’s overnight policy rate to 2.75%. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) said the stance of monetary policy continues to accommodate and support economic growth. Malaysia’s economy expanded at an 8.9% annual rate in the second quarter, following growth of 10.1% in the first quarter. Although growth is moderating amid global uncertainties, Bank Negara governor Zeti Akhtar Aziz says it could exceed the official 6% target for the full year. Inflation rose slightly, to 1.6% in the second quarter from 1.3% in the first quarter, due mainly to a rise in food prices, but the MPC says inflation is likely to remain moderate going into 2011. The International Monetary Fund expects Malaysia’s economy to grow 6.7% this year and 5.3% in 2011. The IMF says Bank Negara has appropriately shifted its monetary policy through a measured pace of rate increases. This will help prevent financial imbalances in an environment of low interest rates while still supporting demand and limiting the drag from necessary fiscal consolidation.

New Zealand

Alan Bollard

Grade: B

Earlier this year, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand ended most of the special liquidity measures it introduced during the financial crisis. In June the central bank increased its key rate by a quarter point to 2.75%, stating that growth in the economy was becoming more broad-based. Another quarter-point hike, to 3%, followed in July, but Reserve Bank governor Alan Bollard said that the outlook for economic growth had softened and that the pace and extent of future rate increases could be moderated. “Compared with some past recoveries, this is certainly not a fast or robust one,” Bollard said. Rising unemployment and falling home sales, along with new concerns about the global recovery, could cause the Reserve Bank to pause in its tightening. Nevertheless, it seems to be committed to the gradual withdrawal of monetary stimuli to keep inflation expectations subdued. The fluctuating value of the kiwi currency is another key concern for New Zealand’s export-dependent economy. Bollard says medium-term price stability is the key objective of monetary policy.

Philippines

Amando Tetangco Jr.

Grade: B

The Philippine central bank has kept its key policy rate at a record low of 4% since July 2009. President Benigno Aquino, who was elected in May, has pledged to make the country more business-friendly and to encourage public-private partnerships in infrastructure. Aquino inherited an economy that expanded by 7.9% in the first six months of 2010, its fastest first-half growth in 22 years, thanks in part to election spending and strong growth in the region. While the central bank appears to be taking a risk by keeping rates low in the face of fast economic growth, it has been regularly ratcheting down its inflation forecasts as price pressures have eased. Central bank governor Amando Tetangco says low US interest rates will enable the government to raise funds from the international capital market at relatively low cost to finance the country’s huge budget deficit. Tetangco says that manageable inflation gives the central bank flexibility to continue to be supportive of the government’s growth objective.

Singapore

Heng Swee Keat

Grade: B

Singapore’s monetary policy is implemented based upon an undisclosed band for the Singapore dollar. In April 2010, after the economy surged 32% from the previous quarter, the Monetary Authority of Singapore moved the currency band upward and shifted to a gradual appreciation of its currency. The MAS says it does not expect the strong pace of economic growth seen in the first half of this year to be sustained. For 2010 as a whole, it estimates that the economy will expand by between 13% and 15%. In its annual assessment of Singapore’s economy, the International Monetary Fund said in July that the Singapore dollar appeared to be somewhat weaker than its medium-term equilibrium level. The IMF urged Singapore policymakers to remain vigilant on the outlook for growth and prices, noting that further adjustment of monetary policy might be needed.

South Korea

Kim Choong Soo

Grade: Too early to say

Kim Choongsoo was named governor of South Korea’s central bank in March 2010. In July the Bank of Korea raised its key interest rate by a quarter point to 2.25%. The rate had remained at a record low 2% for 16 straight months. Kim said in August that the bank’s monetary policy stance was still highly accommodative, and he hinted at the need to raise the rate further. Exchange-rate stability is the central bank’s main concern, he said, although the bank does not have a target level for the won. South Korea’s economy grew faster than expected in the second quarter. Gross domestic product increased 1.5% from the previous quarter and was up 7.2% from a year earlier. It is expected to rise 5.9% for the year. Kim says global economic and financial conditions will play a role in determining the pace of future interest rate increases. The consumer price index rose 2.6% in July from a year earlier and was within the central bank’s annual target range of between 2% and 4%.

Taiwan

Fai-Nan Perng

Grade: A

Taiwan’s economy is enjoying strong growth and low inflation, thanks in no small part to timely and effective adjustments in monetary policy. The central bank moved quickly and decisively during the global financial crisis to soften the impact of external shocks on the economy and the credit markets. As the economy began recovering in the second half of 2009, the central bank started mopping up the excess liquidity by issuing certificates of deposit. In June 2010, the bank raised its benchmark interest rate by an eighth of a point to 1.375%. It cited rising property prices, expanding exports and investment and improved employment conditions. Taiwan’s gross domestic product expanded at a 12.5% annualized rate in the second quarter of 2010, following growth of 13.7% year-on-year in the first quarter. The country’s export-dependent economy has become increasingly linked with China’s. The exchange rate of the New Taiwan dollar has contributed to economic stability by rising when inflationary pressures increase and falling when there is a slowdown in economic activity.

Thailand

Tarisa Watanagase

Grade: B

Tarisa Watanagase, the first female governor of Thailand’s central bank, completed her four-year term on September 30. During her final year in the position, she has been forced to weigh the damaging effects of political unrest on the economy against signs that growth was accelerating at a faster pace than expected. Political clashes in April and May killed at least 89 people and shut down large sections of downtown Bangkok. After keeping its benchmark rate at 1.25% throughout the first half of this year, the Bank of Thailand raised the rate a quarter point in July and again in August. Despite the political turmoil, gross domestic product rose 9.1% in the second quarter, as exports soared. Exports rose 46% in June from a year earlier, the most in 18 years. The Thai cabinet in July approved the appointment of Prasarn Trairatvorakul as the new governor of the Bank of Thailand. Prasarn, who was president of Kasikornbank, takes over the central bank job on October 1. Property prices are rising, and inflation is expected to pick up in 2011, giving Prasarn an early test of his inflation-fighting abilities.

MIDDLE EAST & AFRICA

Israel

Stanley Fischer

Grade: A

Israel’s economy recovered quickly from the global crisis, and the Bank of Israel was the first central bank to raise interest rates last year. The quarter-point increase in August 2009 came sooner than most analysts expected. It brought the benchmark rate to 0.75% from a record low of 0.5% and followed the removal of some other expansionary monetary policies. The Bank of Israel has made it a habit of surprising the markets under its governor, Stanley Fischer, former first deputy managing director at the International Monetary Fund. Fischer has mastered the element of surprise as an effective tool in curbing inflation expectations. In a series of rate hikes that brought the benchmark rate up to 1.75% on July 26, 2010, the Bank of Israel brought a rising inflation rate back within its target band. The latest increase in rates was designed to help prevent a real estate bubble, with the country’s housing prices up more than 20% from a year ago. The Israeli economy has solid economic fundamentals, as well as conservative banking and capital markets. It also has Stanley Fischer, who has agreed to serve a second five-year term, to help steer it through whatever turbulence lies ahead.

Saudi Arabia

Muhammad Al-Jasser

Grade: B

Saudi Arabia lacks a truly autonomous monetary policy, since its currency is pegged to the dollar. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency has left interest rates unchanged since it lowered the key repurchase rate by a half-point in January 2009 to 2%. Inflation in the Kingdom has climbed to around 5.5%, but the increase is mainly due to higher food and housing costs, and monetary policy is not the appropriate tool to respond to such supply shocks, according to central bank governor Muhammad Al-Jasser. Saudi Arabia’s inflation is creating negative real interest rates, stimulating money and credit growth. The Saudi government has boosted public spending over the past two years to counteract the effects of the global economic crisis, and the money supply is finally beginning to grow. The Saudi banking sector is strong after increasing loan-loss provisions, although bankers remain reluctant to lend following their recent experience with some troubled family-owned firms. The Kingdom’s broad M3 money supply rose 4.3% at an annual rate in June. The course of the global economy and oil prices will have a major long-term effect on the Saudi economy, but all signs at the domestic level currently look promising.

South Africa

Gill Marcus

Grade: B

Gill Marcus has done a good job in her first year as governor of the Reserve Bank of South Africa. After lowering the benchmark interest rate by a half-point on March 25 to 6.5%, the lowest in 12 years, the central bank dug in its heels. For six months, Marcus resisted calls from political leaders and labor unions to lower the benchmark rate further. South Africa cannot make employment creation its priority and then at the same time agree to wage and salary increases that are, in some cases, double the level of inflation, she says. In addition, the Reserve Bank has no specific target for the rand’s value, Marcus says. She sees no point in seeking a weaker currency when the benefits will be eroded by inflation. Despite the moderation of inflation to within target range, inflation expectations have remained relatively elevated. The rand exchange rate has been volatile, responding to changes in global risk aversion related to events in the US and Europe. Low interest rates in the developed economies have resulted in a search for yield, and South Africa, like other emerging markets, has received its share of capital inflows. With the rand falling, however, in early September the central bank finally yielded to the pressure and dropped rates to 6%.