As risk appetite returns to the global markets, the dollar could lose what little support it has gained from its role as a safe-haven currency during the recent period of turbulence, analysts say.

As risk appetite returns to the global markets, the dollar could lose what little support it has gained from its role as a safe-haven currency during the recent period of turbulence, analysts say.

The dollar will remain supported as long as risk aversion remains in place, mainly due to ongoing safe-haven flows into US treasury bonds and bills, says Samarjit Shankar, Boston-based director of global strategy for the currency group at The Bank of New York Mellon. “However, as risk appetite returns, the dollar may find itself in a lose-lose situation. As markets stabilize, dollar-based investors may once again venture into riskier assets and re-enter positions in emerging markets bonds and equities,” he says.

At the same time, the outlook for lower federal funds rates in the coming months, as the US economy slows while non-US economic growth remains relatively resilient, will begin to weigh on the dollar, according to Shankar.

Currencies were trading in fairly narrow ranges in early September, as market psychology improved following the initial shock from the subprime fallout, but investor sentiment remained shaky. “There is growing debate in the markets about the outlook for emerging markets if this crisis drags on,” says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman in New York. “To us, the biggest risk is that the crisis drags on long enough to substantially impact global growth,” he says.

While some of the big emerging market countries, such as Brazil, Russia, India and China, are not particularly vulnerable to a global economic slowdown because of the strength of their local economies, the smaller export-dependent countries would suffer more, according to Chandler.

Emerging Safe Havens?

“Since this current crisis began in the United States and other developed markets, emerging markets can certainly outperform the developed economies in terms of equity markets and exchange rates,” Chandler says. “Some are even bold enough to talk about emerging markets as a safe haven—probably with tongue planted firmly in cheek—but that’s overstating the point,” he says.

The drying up of liquidity in the financial markets is the next crucial factor, and here, too, emerging markets are much less vulnerable than in the past, Chandler says. Most are running current account surpluses, making them less dependent on capital inflows.

In addition, most of the major emerging market countries have reduced their external debt and lengthened the maturity of their outstanding debt. “Emerging market fundamentals are the best we have seen in a generation, making them well situated to ride out this storm,” Chandler says. While China confirmed that one of its large banks had about $10 billion of subprime exposure, most emerging market financial institutions have so far revealed few if any losses and minimal holdings.

“Transparency has never been one of the strong suits for emerging markets, and it would be naïve to think that they were not caught up in the subprime trap, too,” Chandler says. “Keep an eye on this issue, but for now we think solid global growth will underpin investor interest in emerging market equities, which will in turn help support those currencies,” he says.

Yen Rises Across the Board

Meanwhile, downturns in US and global equity markets in late August weighed on the carry trade, shoring up the yen versus higher-yielding currencies. “The yen has risen across the board on a combination of subprime concerns and worries of an economic spillover to the US overall economy,” says Ashraf Laidi, chief foreign exchange analyst at CMC Markets US, based in New York. Although expectations of a Bank of Japan rate increase have been delayed, the yen continues to benefit from regular bouts of carry-trade unwinding resulting from renewed volatility or economic concerns in the United States, he says. In the carry trade, investors borrow low-yielding currencies to fund purchases of higher-return assets.

“One increasingly clear element about the Japanese currency is that the uptrend remains firmly cemented, and recent profit-taking has been a buying opportunity,” Laidi says.

As widely expected, the Bank of Japan left policy rates unchanged at 0.5% in August by an 8-to-1 majority vote, the same as in July, with Atsushi Mizuno casting a dissenting vote. Mizuno argues that Japan’s low interest rates may have contributed to causing the subprime problem.

“The turbulence in the global financial markets and the increasing downside risk for the US economy most likely dissuaded policymakers [at the BoJ] from raising interest rates,” Kiichi Murashima, chief economist at Nikko Citigroup in Tokyo, said in a recent report. “We believe that a rate hike will likely be delayed until the first quarter of 2008, as it will probably take some time before policymakers have a clearer understanding of the impact of the financial market turbulence on the US economy and its implications for the Japanese economy,” he says.

“Moreover, we expect a sharp appreciation of the yen this year, which will probably delay the BoJ’s rate hike,” Murashima says. “The likelihood of sharp yen appreciation along with a moderate downward revision of our US economic outlook have prompted us to trim our Japanese GDP growth forecasts,” he says.

Rising Yen Hurts Japan

Nikko Citigroup now expects real gross domestic product in Japan to grow by 2% in the current fiscal year and 1.7% in fiscal 2008. It estimates that a 10% appreciation of the dollar against the yen would lower Japan’s GDP growth rate by about 0.3 percentage points the following year.

Consumer spending in Japan is likely to show renewed weakness, Murashima says, as more signs of sluggishness have emerged in recent months. “If, as we expect, GDP-based consumer spending data for the third quarter, which will be published in mid-November, show outright declines, it would make a subsequent rate hike in the following months extremely difficult, similar to the situation that occurred last December and January,” he says.

As market participants’ fears about the subprime crisis ebb and flow, yields will continue to gyrate over the near term, says Chandler of Brown Brothers Harriman. “However, we expect bond yields globally to resume rising over the medium term on the outflow of safe-haven buying,” he says.

The renegotiation of the Home Depot deal was a positive development for credit markets and showed that merger and acquisition activity can continue, but with tougher terms all around, according to Chandler. The home-improvement retailer in late August sold its HD Supply unit to a group of private equity firms at a discount. Home Depot slashed the original $10.3 billion sale price to $8.5 billion. Meanwhile, the three private equity firms taking part in the transaction agreed to invest $150 million each in the business, bringing their total equity commitment up to $2.4 billion. Home Depot agreed to retain a 13% stake in the business.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign Wealth Funds

As US investors returned from their Labor Day holiday in early September, the latest blow to the dollar was a report that Qatar, a Gulf nation rich in natural gas and one of the fastest-growing economies in the world, was shifting some of its dollar-denominated investments to Asia to offset the weakness in the dollar.

“Most significantly, the announcement did not refer to the Qatari central bank’s reserves, which stand at no more than $12 billion, but to the state’s sovereign wealth fund of $50 billion,” says CMC Markets’ Laidi. “There has been much complacency by market pundits dismissing Gulf states’ intentions to diversify their dollar reserves because of the relatively small size of their central banks’ currency reserves,” he says. However, these nations’ sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) hold about 10 times the amount of their central bank reserves with the funds, he says. These funds are mandated to the asset-management arms of US and European fund managers, and the assets are allocated across a wide array of investments.

The SWFs, which are mainly based in the Middle East and Asia, already control funds exceeding $2.5 trillion, making them 50% larger than the global hedge fund industry. They are basically trust funds that can be drawn on to meet pension or state liabilities in the future. Morgan Stanley estimates that SWFs will control more than $12 trillion of assets by 2015.

Abu Dhabi’s Is Biggest

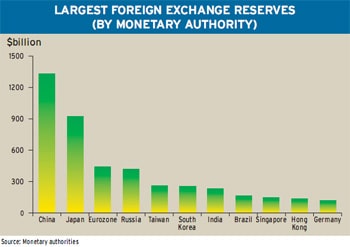

The biggest SWFs by assets include the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, with $875 billion; the newly formed China Investment Company, with $210 billion; and Temasek, the Singapore government pension fund, with more than $100 billion. Altogether, some 25 countries have set up state-run funds to invest foreign exchange reserves.

The Qatar Investment Authority’s move to diversify its assets away from the dollar had been expected for a very long time, says Dennis Gartman, editor and publisher of Virginia-based investment advisory service The Gartman Letter. “No one is to be surprised that Qatar’s or any other nation’s sovereign fund is diversifying away from the dollar,” he says.

Delta Two, the QIA’s fund vehicle, acquired about $1.5 billion worth of stock in British supermarket chain J. Sainsbury in June. A month later it announced an $18.8 billion bid to buy the rest of the company. Kenneth Shen, the authority’s head of strategic and private equity, told a conference in Dubai in early September that the fund’s investment strategy is return-focused and opportunistic. He said the drive to increase the QIA’s exposure to Asian investments was, in part, because it is underweighted in the region in its investment portfolio and also because the risk-return profile of Asian assets is attractive.

The Kuwait Investment Authority’s $213 billion fund also is moving away from assets priced in dollars, as well as euros and British pounds, and toward Asian currencies such as Malaysian ringgit, the South Korean won and the Indian rupee.

Long-Term View

Shen said the Qatari fund differs from a hedge fund or private equity fund in that it takes a longer-term view. “How we perceive risk-returns is no different from typical funds, but one of the differences lies in the time horizon and our ability to think long term,” he said.

Shen downplayed the reluctance of many countries in the West to accept investments from sovereign funds, particularly from the Middle East. “We have been reasonably well received,” he said. “We try to keep a low profile. On the other hand, you do need to allay some of these concerns and not necessarily be a black box,” he added.

Shen’s comments gave the investment world a rare insight into one of the secretive sovereign funds from the Gulf, according to Gartman. “It is reasonable, then, to assume that if Qatar, one of the United States’ closest friends in the Gulf, is making it quite clear that it is diversifying away from the US, the other sovereign funds are, or shall be, doing the same, and in size,” he says.

China Investment Company’s purchase of a $3 billion stake in the initial public offering of Blackstone Group gave it a nonvoting minority stake at a discount of 4.5% to the IPO price. The Chinese government says it does not expect Blackstone to provide any advice in exchange for the investment. Abu Dhabi recently bought a minority holding in a listed investment vehicle of private equity group Apollo Management.

China Development Bank and Temasek invested $4.8 billion in Barclays of the United Kingdom in July to help it in its bid to acquire ABN AMRO, based in the Netherlands. Sovereign wealth funds are expected to invest in a broader range of assets than a typical central bank.

“Sovereign wealth funds are a financial force to be reckoned with and will be a key source of capital for the foreseeable future,” says Peter Hall, vice president and deputy chief economist at Export Development Canada. The funds are a source of stability and are prolonging growth at the top of the cycle, he says.

“Governments around the world are cashing in on recent good economic times,” Hall says. “Sovereign wealth in a wide array of nations has ballooned over the last few years, and further growth is likely in the coming years.”

Growing Trade Surpluses

Trade surpluses as a share of gross domestic product are at the highest levels recorded in generations and have catapulted official reserves in numerous countries to extraordinary levels, according to Hall. For many countries, skyrocketing oil and other commodity prices have resulted in a windfall, he explains. In others, globalization has vastly increased production and net exports. “And since high commodity prices and globalization will be with us for some time to come, the windfall is no flash in the pan,” he says.

Surplus funds have accumulated in high-saving countries, deepening the global pool of available capital and spurring further investment by lowering the cost of funds, Hall says. Many countries are actively accumulating funds in years of plenty, which should further insulate them from global growth shocks, he adds.

“The rapid rise in sovereign funds underscores a shift in financial power away from the United States and toward a new class of creditor nations across the globe,” according to a report by Los Angeles-based investment management firm Payden & Rygel. It says that SWFs could continue to be among the biggest buyers of bonds and equities, which include so-called “risky” assets, such as high-yield bonds and emerging market securities.

The Bush administration has warned that the spread of SWFs could create new risks for the international financial system. It has called on the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to examine their behavior and create possible codes of conduct for them.

“There’s certainly no need for dramatic action,” says Simon Johnson, economic counselor and director of the IMF’s research department, writing in the September issue of Finance and Development, a quarterly magazine published by the fund. “There’s no apparent reason to see the continued existence of these funds as destabilizing or worrying,” he says.

The situation involves sensitive issues of national sovereignty, and member nations of the IMF need to begin a constructive discussion of what information they are willing to share, what information it makes sense to ask for, and what information would be useful for global economic and financial analysis, according to Johnson.

Gordon Platt