As the region looks to diversify economically, Gulf banks get in line with global rules and standards. It’s not easy.

Regulation: The word implies headaches and stress to financial executives, and especially so in the post-crash decade as they wrestle with the ratcheting-up of the Basel accords, anti-money-laundering actions, and other measures to promote cross-border harmonization and discourage corruption.

The nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council until recently were insulated from many of these pressures, since their economies were cushioned by generally high oil prices and most of their banks navigated the 2007-08 crisis with minimal damage. With regional tensions rising and oil prices declining, however, regulators and financial institutions understand that they no longer operate in a stable, cosseted environment. Given their location and history, GCC banks face specific regulatory challenges—and also a rare opportunity to reboot and design a banking system that can prosper through the next stages of the region’s development.

The twist, for Gulf institutions, is that most of the international standards for finance were designed in either Europe or the US. “In the Middle East, we face the challenge of interpreting these requirements to suit the needs of our own unique financial services market,” Deloitte notes in its Financial Services Regulatory Barometer Middle East 2018. “We also arguably face different regulatory risks and therefore have different regulatory priorities. These include the impact of the sustained low oil price on the availability and cost of liquidity, the risks from existing and perceived financial crime activities [and] the rise of nonperforming loans.”

Topping the list are the Basel III standards, along with anti-money laundering and combating financing terrorism measures (AML/CFT).

Erected as a response to the financial crisis, Basel III still faces skepticism from GCC institutions, which see it—and especially its increased capital requirements—as an unfair price to pay for a mistake they didn’t commit. Yet, they are slowly getting on board. Saudi Arabia was largely compliant as early as 2015, and the United Arab Emirates announced a series of compliance-related measures in 2017. Qatar, Oman and Bahrain are looking to implement it by 2019, while Kuwait faced some domestic political trouble and delayed it until 2021.

“For forward-looking banks, the Basel III requirements can be much more than an administrative burden and a drag on growth and profitability,” argued Jihad Khalil, Daniel Diemers, and Peter Gassmann in an early analysis for PricewaterhouseCoopers’ Strategy& consulting group. “Rather, financial institutions should consider the new rules as a catalyst to upgrade their capabilities and as a call for thoughtful, balanced improvements of their risk-return profile.”

Challenging Friendships

Another top priority for GCC banks—due to the close proximity of conflict zones and internationally sanctioned countries—is AML/CFT compliance. The slightest mistake can kill a bank’s reputation in the blink of an eye; and as the risk appetite of large foreign institutions declines all around the world, GGC banks increasingly fear being cut out of the global financial system. In 2015, 39% of banks in 17 Arab countries reported a “significant decline” in their correspondent banking relationships, according to a report from the IMF and Arab Monetary Fund.

To face this challenge, some banks applied severe derisking policies, closing accounts and ending relations with certain clients. Middle Eastern financial institutions also invest massively in compliance, a recent study by Deloitte and Reuters shows. More than half (58%) of respondents reported that their firm spent more on anti-financial-crime activity and compliance over the last two years than in the past, and 72% expect to spend more going forward.

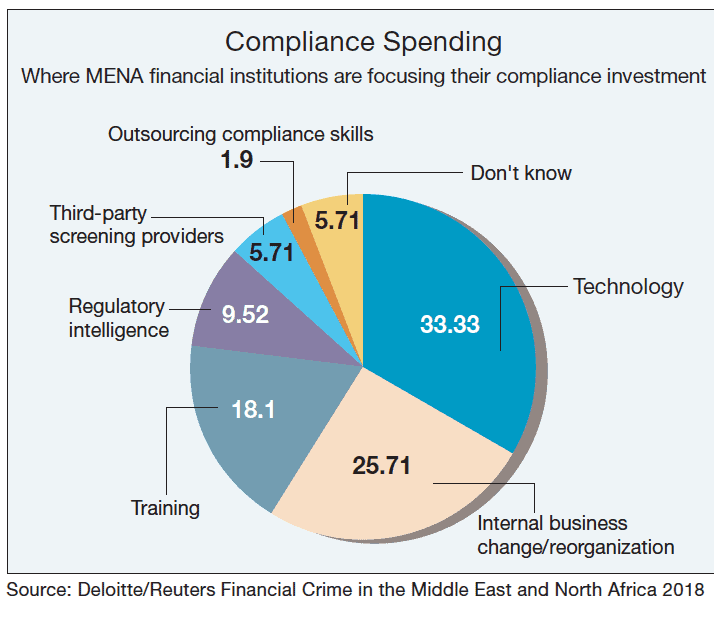

Respondents also indicated that technology was the main target of compliance investments.

Emirates NBD is a good example of this trend. Dubai’s largest bank has committed $272 million to digital transformation and now offers services such as a biometric signature option, a fingerprint-secured banking application, and the region’s first blockchain-based checkbook.

While the GCC forms a natural geographic-commercial unit, the Gulf region is not Europe.

Like the European Union, the GCC has long promoted regional integration. It once worked actively to establish a single currency. But for the six states, harmonizing practices with their neighbors can be as difficult as applying regulations drafted on the other side of the globe. When the member states couldn’t agree on where to put a central bank, the single-currency project fell through in 2009. Today, GCC-wide harmonization is arguably more difficult than it was then, given the war in Yemen, the blockade of GCC-member Qatar, and the recent Saudi crackdown on key business and political figures.

On the surface, the Gulf states have similar economic profiles, but in practice, there are large divergences. The UAE has the largest banking sector, with $734 billion total assets in 2017, followed by Saudi Arabia with $615 billion. Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman are substantially smaller. The financial sector is scarcely integrated at the regional scale; each country maintains high barriers to entry and protectionist laws. As a result, most banks are domestically owned and exist in neighboring countries only in the form of branches. This is an obstacle to the development of foreign banks in the GCC, as they get restricted licenses, and to the development of large regional banking groups.

“A key challenge that many banks looking to expand face is that they will have to recognize and meet the requirements of the jurisdiction in which they plan to expand,” Deloitte’s Financial Services Regulatory Barometer Middle East 2018 concludes. “The more complex the group becomes, the more complex regulatory compliance becomes.”

As conventional actors stall, part of the solution may lie with fintechs. Today, the startup world is the one pushing for reform, with more and more e-businesses looking to scale regionally and a growing regtech industry demanding regulatory sandboxes to spur innovation and development. While Gulf governments are not moving as fast as those in other regions, they are showing some inclination to do. In June, the Central Bank of Bahrain issued its first sandbox license to a digital asset exchange. Fintech might even succeed where traditional finance failed. Last year, Saudi Arabia and the UAE started discussing the development of a common digital currency.

Cultural Shift

Ultimately, the goal for GCC banks is to not simply accept regulations and assign a department to enforce them, but to make their substance part of the “corporate DNA.” “Compliance is no longer a requirement; it is becoming a culture that is spreading all over the bank,” says Ali Awdeh, director of research at the Union of Arab Banks. “This implies a lot of training and increased transparency.”

They still have a long way to go. Back in 2017, Reuters and Deloitte indicated that 44% of compliance officers in the MENA region lacked confidence in their organization’s AML program. Over a third of respondents pointed to an overall lack of understanding of the regulatory environment and 22% said they were overwhelmed by the pace and complexity of regulatory updates. A year later, 47% point to a lack of management support to explain their lack of confidence.

Change is underway, but it takes time.