As the US has extended its regulatory reach beyond its own borders, other jurisdictions have followed its lead. Global corporations face an ever-growing burden in maintaining compliance with increasingly complex regulatory and reporting regimes. This is affecting their budgets, their structuring and also their strategy.

Over the past few years a series of regulatory developments have conspired to redefine the corporate compliancelandscape, causing a spike in the related budget and staffing needs of financial and nonfinancial firms alike. It has given rise to a new position at many companies—that of the global chief compliance officer—and huge investments in new systems and processes. The way firms manage their compliance efforts has drastically changed—and will require constant review as global market reform continues to gain momentum.

What began as a US-centric trend to increase regulatory reporting and related requirements—and subsequently the time and effort involved in complying with those regs—has been taking hold in the rest of the world. This global surge has been driven in part by the US authorities’ embracing of the notion of extraterritoriality [the application of US jurisdiction and regulations outside the borders of the US] to mount enforcement actions against foreign entities, causing a rush of similar legislation to be passed in response.

In addition, there has been a push in a number of global economies to enact regulatory and legal changes that increase market transparency and reduce corruption. “This effort is gaining momentum, becoming worldwide,” says Adam Lurie, a partner in the New York law firm Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft. “I don’t think there is any end in sight.” Today acronyms like FATF (Financial Action Task Force), OFAC (the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control), KYC (Know Your Costumer), FCPA (the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act) and MiFID 2 (the EU directive on markets in financial instruments), among many others, are the stuff of nightmares for compliance professionals everywhere.

The origins of the current regulatory wave can be traced to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, in the US, which triggered stricter norms for combating money laundering. Around the same time, the collapses of corporations like Enron prompted a rethinking of anti-fraud controls. More recently, the global financial crisis has inspired tougher regulations across the world, while high-profile corruption cases at major multinationals have persuaded authorities to tighten the screws on bribery. And a revamped focus on sanctions as a foreign policy tool has caused the overhaul of everything from payment protocols to third-party due diligence.

“I joke that there is a new medical condition called compliance stress disorder,” says Steven Powell, co-head of forensics at law firm ENSafrica in Cape Town. “In each jurisdiction there is a multitude of anti-money-laundering (AML), anti-terrorism, anti-corruption and sanctions requirements to keep track of and which continue escalating.”

“Extraterritoriality is getting more important by the day,” says Stephen Lock, head of group financial crime prevention and security at Old Mutual in London. However, many local firms with seemingly little exposure to the dollar might not be fully aware of how easy it is to fall into American regulators’ hands.

“Many companies in Africa trade shares in the US, even via American depositary receipts, but don’t realize this renders them subject to US laws,” says Powell. “US authorities threaten that if they want to go after companies that pay bribes, they can even establish jurisdiction based on an email thread routed through a US server or payments routed through an American bank.”

A cascade effect is created, whereby companies have an incentive to try and preempt any possible enforcement action by putting in place, early and decisively, a strong compliance program. “And this cannot just be on paper,” says Gwen Hassan, managing attorney of regulatory compliance at global manufacturer CNH Industrial, whose North American headquarters are located outside of Chicago. “If you encounter a situation where anybody you are affiliated with is paying a bribe anywhere in the world, you should be able to demonstrate to regulators that you have a lot of policies in place to prevent this from happening and, therefore, this is only a one-off occurrence due to a rogue employee. And to be able to do so, you need to have staff, to have invested in different processes, systems and technologies.” The long hand of the US government is therefore compelling compliance spending around the world.

GLOBAL REGULATORY PUSH

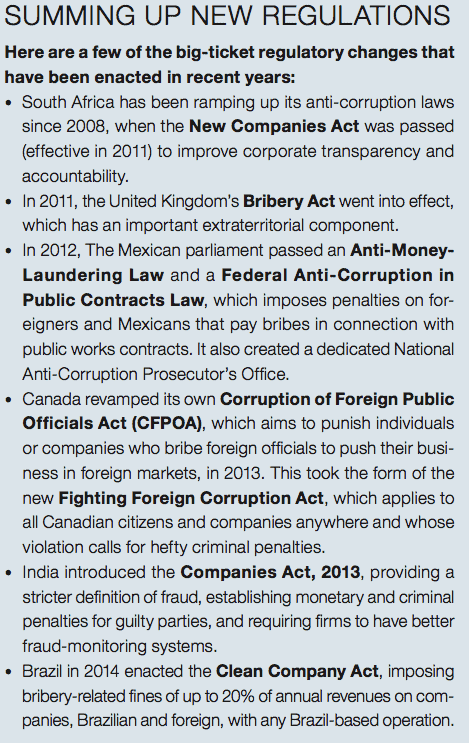

In addition, more jurisdictions are taking their cue from Washington and requiring greater transparency and reporting to reduce corruption and gaming of the system. South Africa has been ramping up its anti-corruption laws since 2008. The United Kingdom’s Bribery Act, which also has an extraterritorial component, went into effect in 2011. Mexico, Canada, India and Brazil have all followed suit. “These are only the more developed countries in their regions,” says CNH Industrial’s Hassan. “A number of smaller countries in South America and Eastern Europe are still working on enactment and enforcement of corruption prevention regulations. In terms of corruption enforcement alone, we have only reached the tip of the iceberg.” In the AML space, specialists are awaiting the Fourth Money Laundering Directive in the EU and assessing the impact of recently enacted legislation across Asia.

Financial regulations tell a similar story, with the US and the EU leading the way and other governments following closely behind. Take the Asia-Pacific region. “A bank like ours is faced with a particular degree of complexity due to the interaction between many internationally accepted rules with an equal if not greater number of local laws and regulations,” says Lam Chee Kin, group head of compliance at DBS Bank in Singapore. Dante Fuentes, chief compliance officer for Security Bank in Manila, describes his own experience: “The central bank of the Philippines (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas) issued a whole new compliance rating system to actively promote the safety of the national banking industry.”

The same interplay of rules is visible in international sanctions. The US and the EU have the most-far-reaching ones in place, against Iran, North Korea, Russia, Sudan and Syria, while the United Nations’ often provide a basis for legislations elsewhere. “Some countries will have their own sanctions over and above these, for their own political reasons,” notes Michael O’Kane, partner and head of business crime at Peters & Peters Solicitors in London. The UK, Switzerland, Canada and Japan have their own lists. For a time, Australia and New Zealand imposed sanctions on Fiji. There also exists an Arab League boycott of Israel.

All this together makes for sleepless nights for corporate compliance executives and takes the obligations of third-party due diligence to a whole new level.

|

BEYOND MONETARY COSTS

Unsurprisingly, the catalog of companies that have ended up in regulators’ sights is long and getting longer. Just in March in the US, Commerzbank, global oilfield services company Schlumberger, and Paypal all agreed to pay hefty fines (respectively $1.5 billion, $237.2 million and $7.7 million) for allegedly violating a mix of anti-money-laundering laws and sanctions. More famously, BNP Paribas settled US sanction-related charges for $8.9 billion in 2014, the year that Credit Suisse was fined $2.6 billion for abetting tax evasion. Wal-Mart is under investigation for bribing officials in Mexico, a probe that has already cost it more than $400 million, before any penalty is assessed. Since 2008, Siemens has paid more than $1.6 billion in fines in four jurisdictions—the US, Germany, Turkey and Greece. And last year GlaxoSmithKline was fined nearly $500 million by the Chinese government for paying bribes to doctors.

The costs are manifold, and include legal fees, hiring outside investigators and then hiring consultants to build up a remedial compliance program and monitor it for a period of time (in Siemens’ case, all of this came up to approximately an extra $1 billion).

But the full damage to a firm from an enforcement action goes beyond monetary levies. A recent Thompson Reuters report listed other farther-reaching penalties, like the negative impact on a firm’s share price, stricter liquidity requirements, and criminal convictions for executives. Not to speak of the longer-term impact on a company’s brand, particularly in the age of social media, when bad news spreads at lightning speed. Axel Klappstein, head of compliance at Berenberg Bank in Germany, notes: “Above all [noncompliance may result] in a loss of or damage to the [firm’s] reputation.”

The flip side, though, is that compliance also represents an opportunity for a firm to improve its credibility with the public while allowing it to safely enter markets that, otherwise, it might have to avoid altogether.

“At the bank I used to work for, after we set up our sanctions and export controls program, we could offer clients services that others would simply say no to, because of their inability to manage the sanctions risk,” says Martijn Feldbrugge, owner of Business and Sanctions Consulting Netherlands. “Compliance generated business and therefore money.”

INCREASING INVESTMENT

Motivated by both the stick and the carrot, companies have been ramping up their dedicated spending. In a 2014 Deloitte survey, 50% of respondents said their company had a stand-alone chief compliance officer, compared with 37% in 2013, while three-fourths reported that their compliance budgets had increased over the previous year. “We have tripled the number of compliance staff at holding company level compared to what we had five years ago,” says Thomas Loesler, chief compliance officer at Allianz. “And this is only a fraction of the increase in the overall cost of compliance across the entire organization.”

With compliance staff and budgets also increasing, CNH Industrial has appointed a stand-alone chief compliance officer. “We did historically have someone in charge of compliance, but it was a dual role held by the general counsel,” says Hassan. “It has become increasingly clear… based on enforcement activities and opinions from different government agencies, that for a public company, it is a best practice to have a separate compliance function with direct access to the corporate audit committee.”

But, givien the skyrocketing costs, one key objective is ensuring the best use of investment dollars, which is where technology come in. “In traditional financial services, compliance is more of a manual process,” says John Beccia, general counsel and chief compliance officer at Circle, a consumer finance company that works in bitcoins. “We are finding ways to automate things and leverage technology to give us more information on our customers.” According to advisory firm TechNavio, the global AML software market will grow around 11.5% annually until 2018.

Once a degree of regulatory rationalization is achieved and more consistent staffing and budget levels, and technology, mature, compliance could become less a source of stress and more a point of pride. The pharmaceutical industry provides an interesting, if somewhat unlikely, example: “Banks are going through what the drug industry went through 10 years ago,” says Rady Johnson, chief compliance and risk officer at Pfizer.

“For us the impetus was to address the perception that Big Pharma was misleading people. So we put in place a stand-alone compliance function, and we now have a whole division that did not exist then.” Reportedly, that investment is paying off in terms of reputation, with the industry having regained some of that lost trust back, and money. “In the last couple of years we have been able to reduce our budget, not because we are cutting back but because with ten years under our belt, we have learned to do it more efficiently,” Johnson concludes. “I’d be remiss if I didn’t talk about changing a firm’s culture. Because it doesn’t matter how many systems you have in place, if your culture is not the right culture, you’ll always be pushing a rock up the hill. It is fundamental that each and every employee owns compliance.”

The Chief Compliance Officer Comes Of Age

The protagonist of the 2014 American action thriller Jack Ryan: Shadow Recruit is a CIA operative and anti-money-laundering expert carrying out a covert analysis of banking data in Russia. “You know the industry has made it when Hollywood makes a movie about it,” says John Cusack, global head of financial crime compliance and group money-laundering-reporting officer at Standard Chartered. In his 20-plus years working in the financial industry, Cusack has witnessed the dramatic rise of the compliance profession.

“When I started, compliance was a small offshoot of bank legal departments and, as such, almost universally full of lawyers,” he says. “Whereas now we are a distinct profession with a whole slew of different specializations: auditors, forensic investigators, tech people, risk experts.” The mounting need by both financial and nonfinancial firms for highly qualified professionals and the front-page nature of the recent scandals of corporate malfeasance have made this an increasingly sought-after line of work.

But there’s one important caveat: This is a very hard field to master. “You have to understand the external environment, the regulations, the risks, but also be very knowledgeable about the operations of your firm and have sufficient emotional intelligence to be able to talk to very senior people who have worked their whole life in a particular part of your industry and be credible when you do,” he explains. “Because it is such a difficult job, there are only two types of compliance officers, the good ones and the bad ones… If you’re in the latter category, you will ultimately be found out.”