|

|

An oil worker stands on the deck of a tanker at Bonga offshore oil field outside Lagos.

|

Africa has long been the forgotten continent. Despite enormous wealth in resources, it has historically been blighted by the legacy of colonialism, political corruption and economic mismanagement. Now Africa has been rediscovered: China and India are leading the way in tapping the continent’s commodity wealth and fueling a boom in trade. Meanwhile, economic reform is helping to increase domestic consumption—raising hopes that Africa may enjoy consistent, long-term growth.

To be sure, numerous threats remain on the horizon. The possibility of instability is never far away, and the bloodshed in Kenya following a disputed election highlights how even countries perceived as stable on the continent are vulnerable to political tensions that can have disastrous economic consequences. More generally, escalating food prices could yet do much to jeopardize hard-won fiscal responsibility among many African states and prompt social confrontation.

Moreover, while there are a number of notably successful economies in Africa, it would be wrong to characterize the entire continent as enjoying a political, cultural and economic rebirth. More so than any other region in the world, Africa remains littered with failed states exhibiting examples of the worst political leadership—Zimbabwe’s inflation (officially 164,900% but estimated to be considerably higher) and virtual destruction of economic and civil society being the most obvious example.

One significant factor behind Africa’s economic rehabilitation is the insatiable demand for oil and other natural resources from emerging markets superpowers such as China. “Other than the obvious investment that China has brought to Africa, one of the most positive benefits of its engagement in the region is one of perception,” says Razia Khan, regional head of research for Africa at Standard Chartered in London. “The continent is now seen in a different light because of Chinese involvement.”

China has taken the lead in investment in the region, and trade with the continent is growing at around 20% a year—hitting around $60 billion in 2007, with natural resources flowing one way and consumer goods the other. Much of the investment has been by major companies: State-run China National Offshore Oil Corporation is now the biggest foreign investor in Sudan and aims to become a major player in Nigeria. Similarly, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China bought 20% of South Africa’s Standard Bank Group in October 2007 for $5.6 billion. However, China has a much broader influence on the continent: The China Business Daily newspaper estimates that more than 500,000 Chinese businessmen and merchants now operate in Africa.

In tandem with its increased economic clout in Africa, China has been extremely proactive in engaging politically—and non-critically—with African regimes (sparking Western criticism regarding China’s sales of military equipment to Zimbabwe and its support for the Sudanese government despite its actions in Darfur), with president Hu Jintao making two major diplomatic trips to Africa in 2007. China has canceled the debts of 33 African countries in a bid to win influence and in July 2007 adopted a zero-tariff policy for 454 commodity products from 26 countries in order to encourage trade.

A Late Start for India

India, while slower off the mark in courting African countries, is rapidly expanding its influence. In April it followed China in removing tariffs on a wide range of African commodities and products such as clothing. The reductions cover an impressive 94% of in-bound goods to India from 34 African countries. The move was announced at the inaugural India-Africa Forum Summit in New Delhi, a conscious attempt to mimic the China-Africa Cooperation Forum. India also announced a doubling of credit lines to $5.4 billion and a promise of $500 million in state aid over five years.

|

|

Alsopp:The spread of democracy encourages investment.

|

India’s commercial presence in Africa remains less prominent than China’s, although that could change if India’s largest mobile telecom company, Bharti Airtel, bids for a controlling stake in South African telecom operator MTN, valued at $40 billion, as expected (but not confirmed as Global Finance went to press). The deal would be India’s largest cross-border acquisition and a bold statement of the country’s intentions. It would also highlight the greater importance of private sector firms from India in growing trade with Africa compared to the state dominance of Chinese trade.

There is evidence that India is less willing to engage with politically dubious regimes in order to win business than China, and it is perhaps significant that the country is planning to cooperate with African countries on social projects in areas such as education and health. Given the 2.8 million people of Indian descent living in Africa—a legacy of British colonialism—now that it is engaged with Africa, it may have an advantage over China without needing to cozy up to dictators to the same extent.

Nevertheless, India’s goal is—like China’s—to substantially increase trade, to secure resources and to boost its global influence. India is already heavily dependent on foreign oil, importing 11% of its oil from Nigeria, and is predicted by the International Energy Agency to become the world’s largest net importer of oil by 2025. India hopes to win the support of African nations in its bid to gain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council.

Of course, there are other economic actors at work in Africa. Russia, in particular, has made a concerted effort through state-owned energy giant Gazprom to challenge the existing pattern of oil and gas rights in Nigeria and is thought to have recently approached the Nigerian government about supplanting a number of established US, European and Chinese firms in the country (see feature, page 26). Unlike China and India, which have an absence of domestic energy resources, Russia’s interest looks to be primarily strategic. It is eager to control the only other major alternative source of gas to its own production in order to better manage prices in the European market.

Even the United States, which has traditionally ignored Africa, has recently wooed countries on the continent. In February president George W. Bush made his second trip to the region in a bid to gain favor with resource-rich nations. The United States’ interest in Africa, however, appears to be as much for military reasons (its newly established Africa Command, known as Africom, is as much a bulwark against Chinese expansionism in the region as a way of combating Islamic terrorism) as economic ones.

More to Growth than Commodities

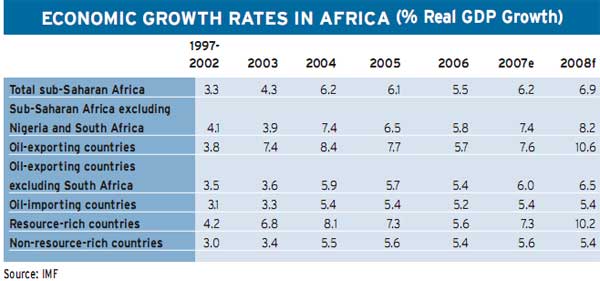

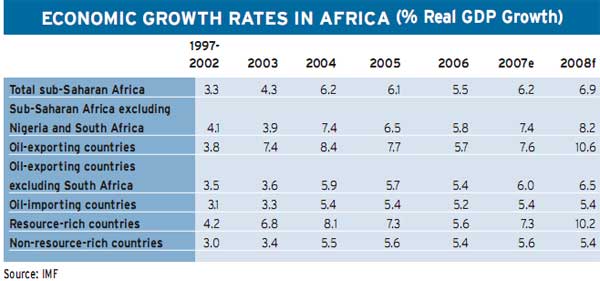

While commodities have certainly contributed disproportionately to Africa’s economic growth in the past five years, they have not been the only driving force. “One of the largest [drivers of growth] has been the increasing global desire to acquire Africa’s natural abundance of commodities (57% of Africa’s exports are fuels and 23% are metals and raw materials), [but] it would be incorrect to say that this has been the sole causal effect of sub-Saharan Africa’s outperformance of global GDP over the period,” says Matthew Pearson, head of African research at Renaissance Capital.

|

Pearson points out that the current commodity cycle has gained its accelerated momentum over only the past 18 months. “In tandem with the increasing global demand for Africa’s abundant commodity assets, the continent’s growth profile has been revived over the past five years due to a combination of its positive terms of trade shock, debt relief, macro stabilization and the resultant significant fall in Africa’s cost of capital,” he says.

Khan at Standard Chartered acknowledges that countries with commodity wealth have grown most rapidly but notes that growth has accelerated for most African countries. Even in countries whose economies are dominated by commodities, much of the growth has come from other sectors. “A good example of the lack of dependence on commodities is Nigeria,” she says. “There, oil-sector growth has actually been negative since 2005, so its strong GDP growth has come from elsewhere.”

|

Since 2001 the correlation between sub-Saharan African growth and global growth—which was previously clear—has broken down, with Africa outperforming the global average with growth of 6% a year or more. To some extent this reflects the rising importance of African oil and may suggest that Africa can now cope better with oil price strength. “Alternatively, it may reflect the improved policy environment in Africa, with reduced fuel subsidies, and therefore less fiscal deterioration in response to oil-related shocks,” says Khan.

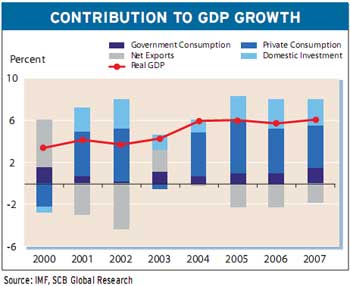

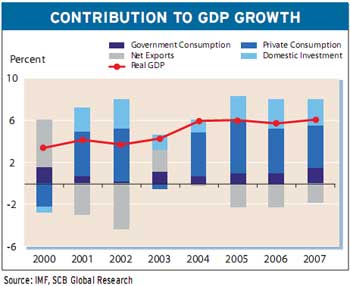

Since 2004 Africa’s rising levels of government consumption and domestic investment—as well as private consumption to a lesser degree—have made a real difference to the region’s overall performance, adds Khan. Increased government consumption and domestic investment can be largely attributed to increased democratization, which has prompted parties to offer policies that promise economic stability and lower inflation.

Jamie Alsopp, manager of the New Star Heart of Africa Fund, which has taken £50 million in investment since it was established in the United Kingdom in October 2007, agrees that the spread of democracy has been important. “The increase in the number of democracies has directly led to tighter fiscal controls in order to bring down inflation,” he says. “That has encouraged investment and growth and resulted in higher domestic consumption, which has allowed African countries to grow regardless of their degree of dependence on commodity prices.”

Troubles Ahead?

If Africa is better placed than is commonly assumed to withstand a global downturn and weaker commodity prices, can it emerge largely undamaged from the current global turmoil? “Arguably, if global growth declines and commodity prices contract, then Africa’s overall GDP growth will be impacted, but we believe that given its low base, its growth will still outperform the global trend,” says Pearson at Renaissance Capital. “Its ability to weather a global economic storm has never been more evident than at present with the current economic malaise and global credit crunch,” he says. “Africa’s cost of capital has collapsed, largely as a result of the significant debt write-downs and relief over the recent years. Interest rates have collapsed, inflation for the continent is in single digits (excluding outlying Zimbabwe), and currencies are appreciating. While global stock markets have been contracting, Africa has been rising, highlighting the lack of contagion and resilience of the continent.”

That is not to say that Africa is immune to shocks, explains Khan, who believes the most worrying of these are the huge increases in food prices that have caused rioting in many developing countries worldwide. She says that higher food prices are a serious threat to African economies because of their potential to dramatically increase inflation—returning Africa to the bad old days of double-digit inflation that it has worked so hard to avoid—and prompt exchange instability. “Obviously, another concern is the potential government responses to domestic pressure on food prices,” she adds. “Given that revenue generation by governments is static or potentially deteriorating, the ability to subsidize food prices is limited, and that could have political implications.”

Of course, the traditional challenges to growth in Africa remain. “Low rainfall can have devastating consequences for a country like Kenya, where 25% of GDP comes from agriculture, or Ghana, which depends on the Volta hydroelectric dam for power,” notes Alsopp. Power shortages across the continent have already curtailed the activity of Chinese smelters. “In addition, there is always the looming potential for political instability following elections as has occurred in Kenya recently,” he says.

A Structural Change?

Africa’s ability to weather the international economic storm will be a critical indicator of whether the region is really enjoying structural change in its economies or just another unsustainable boom that fails to reduce poverty. More than 300 million Africans remain in poverty despite billions of dollars of aid pouring into Africa since colonialism ended. In contrast, trade and investment in Asia has managed to take 400 million people out of poverty in 25 years. Could the same thing now be happening in Africa?

There is evidence that real change is occurring in Africa on a scale not seen before. “The economic windfalls of the resource sector are increasingly finding their way into the real economy, rather than being siphoned off into Swiss bank accounts,” says Pearson. “There are real signs of a middle class developing. They want services, from financial services to quality goods.” He argues that a lower cost of capital, coupled with an increased capital base, is helping to enable businesses to develop viable long-term plans and invest in expansion, helping to drive employment and further add to the development of the middle class. “We are at the nascent stage of a positive economic cycle that is pulling Africa out of poverty,” he says. “There are sadly still significant gaps between the rich and the poor, but for arguably the first time the opportunities are increasing.”

New Star’s Alsopp—much of whose investment focus is on domestic consumption—is optimistic about Africa’s potential. “We believe that economic growth will trickle down, and in many countries there is already a growing middle class,” he says. He points out that Africa could rapidly lose its reputation as being different from other emerging markets. “Russian GDP was at a similar level of Nigeria as recently as the early 1990s. It could eventually catch up,” he says. “Looking further back, at the time of independence Malaysia and Ghana had similar levels of GDP. It is not impossible that their levels of GDP could eventually converge again.”

SAFARICOM IPO POINTS THE WAY

After a year of preparation, in December 2007 the 50 billion Kenyan shilling ($794 million) IPO of Kenya’s Safaricom, the largest cell phone operator in East Africa, was ready to launch, when politics intervened. A disputed presidential election threw the country into turmoil and ultimately left 1,200 dead and 350,000 people homeless.

Incredibly, Safaricom launched just three months later at the end of March—even before a power-sharing agreement was signed between the two major parties that contested the election. “Safaricom is clearly one of the best companies in Africa,” says John Porter, head of ECM for the Middle East and North Africa at Morgan Stanley, global coordinator for the deal. “That kept the deal alive during the political problems.”

Shares in the company, which was 40% owned by Vodafone Kenya and 60% owned by the government before the IPO, were sold to domestic investors at a fixed Ksh5, but international institutions could bid at any price over that, and ultimately the bookbuild price was set at Ksh5.5, valuing the company at more than $3 billion. Although final allocation details had yet to be announced as Global Finance went to press, substantially more than 65% of the offering was sold domestically.

In addition to the political challenges of the IPO, Safaricom faced some technical hurdles. The Kenyan government chose only to list the company on the Nairobi Stock Exchange in order to boost the local market. As most international investors do not have custody arrangements in Kenya, Morgan Stanley created an innovative participation note, which provided the infrastructure for them to trade the stock.

The significance of the IPO, which reduced the government’s stake in Safaricom from 60% to 25%, to Kenya was huge: It is by far the largest IPO in the country and represents 25% of the Nairobi stock exchange’s market capitalization. While no one is claiming that deals like Safaricom will become commonplace in Africa, Porter says that there are a number of $50 million IPOs in the works.

Recent larger deals include the $750 million sale of GDRs for Nigeria’s Guaranty Trust Bank in July 2007, which was the first African company outside South Africa to list on the London Stock Exchange, while the $198 million float of Celtel Zambia was due to complete as Global Finance went to press.

“The emerging markets investor base is expanding rapidly, and Africa is a region where markets have continued to perform against falls elsewhere, encouraging more participation,” notes Porter. “There has long been talk of demutualizing exchanges in the region and encouraging mergers with a view to creating a regional trading center, and there is no doubt that such a move would be beneficial from the standpoint of attracting further investors.”

Jamie Alsopp, manager of the New Star Heart of Africa Fund in London—one of a number of so-called frontier funds established in the past year—says that investment in Africa will inevitably become a more mainstream component of portfolios in the future, although he acknowledges that corporate governance and corruption will need to be tackled in order to achieve this. “In addition, markets are extremely illiquid, making investment more difficult—Nigeria’s market cap is just $90 billion compared to $800 billion in South Africa—but that could change rapidly under the right conditions,” he says.