Capital expenditure continues to see an acceleration from 2020 into 2021, thanks to consumer spending.

One of the key measures business leaders have been eyeing closely to gauge the recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic has been capital expenditures (capex), which took a huge hit in the first two quarters of 2020. The good news is that capex has been enjoying a boom, even outpacing the rebound in consumer spending.

“I think capex was one of the surprising areas of resilience in the last quarter of 2020, and the latest indicators point to solid capex growth right through the first quarter as well,” says Joe Lupton, economist at JPMorgan Chase in New York.

Lupton says that while consumer-goods spending slumped in November and December due to the second wave in US infections over Thanksgiving and Christmas, capex spending actually expanded at about 1.5% a month in the same period. The rest of the world has been slower to recover than the US economy, but there are signs that capex is ramping up elsewhere as well.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, nonresidential US fixed investment, the government’s measure of capex, rose from $2.5 trillion in the second quarter of 2020 to $2.7 trillion in the fourth quarter, just shy of the pre-pandemic level reached in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Lupton says two factors were mainly behind the capex surge: increased corporate profits and the huge fiscal stimuli that governments around the world have been pumping into their economies to fuel a rebound after the devastation of the pandemic.

As Global Finance detailed in a September 2019 cover story, “The Capex Collapse,” after the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in the US in 2017, many companies chose to use their newfound profits to buy back their own shares. But now companies are focusing on real assets to achieve growth and stay competitive.

While capex spending is growing in most areas of the economy, two areas stand out: tech and renewable energy. The one area where capex is lagging is real estate. While investment in structures like warehouses and office buildings is considered a capital expenditure, the pandemic has upended building plans for many companies—with an estimated third of the workforce toiling remotely, companies have put expansion plans on hold in many cases.

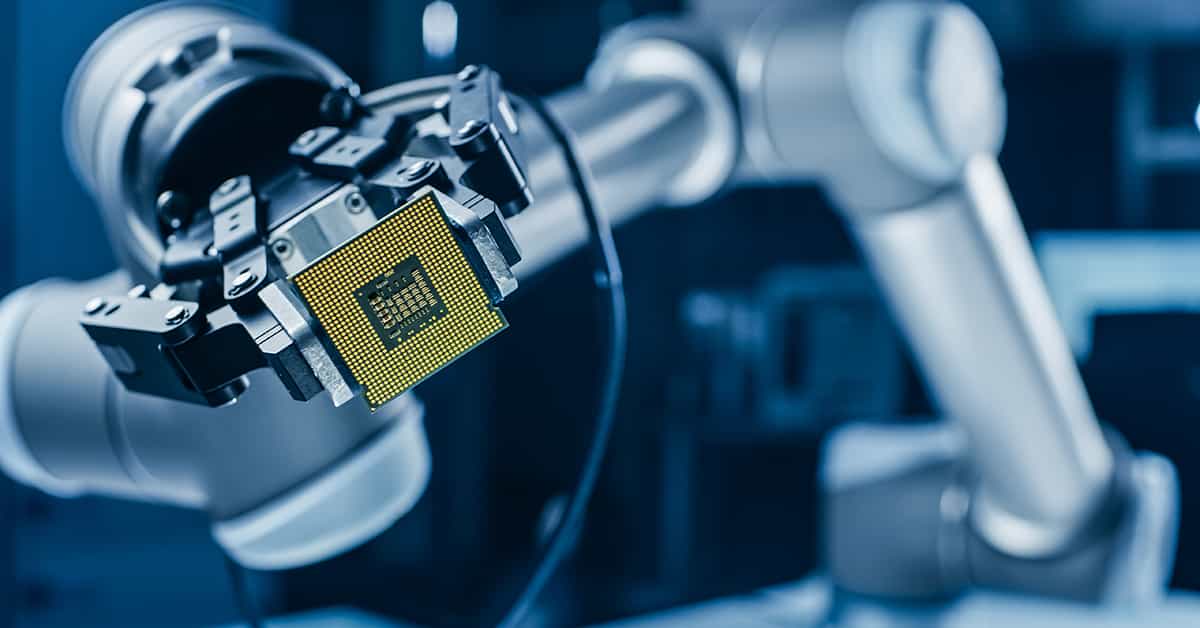

Similarly, the work-from-home phenomenon added jet fuel to the tech sector: Demand for cloud servers, laptops and 5G cellphones exploded. Car companies, fearing a sales debacle in early 2020, slashed orders for the semiconductors that steer and control the latest vehicles and now find that there are no chips available.

As a result of the soaring demand, one of the largest contributors to capex recently has been the race to build new chip fabrication plants. Taiwan Semiconductor manufacturing, the world’s largest contract chip maker, says it is planning to invest $100 billion in the next three years in new facilities, including $25 billion to $28 billion in 2021. South Korea’s Samsung is investing $116 billion by 2030, and Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger says the company is committed to spending $20 billion to build two fabs in Texas.

“The semiconductor content of devices keeps increasing, and every time companies move to smaller process geometry, it’s even more expensive than their last investment,” says Adrienne Downey, director of Technology Research at Semico Research in Phoenix, Arizona, referring to the shrinking of semiconductor designs. “The tools that they have to buy to make the semiconductors keep getting more expensive, so we expect that capital spending is going to increase over time.”

There’s also a political dimension to the rush to invest in new fabrication plants. Because of limits placed on Chinese firms by the Trump administration, companies are expanding production in the US. In addition to the two new Intel plants, TSMC is building a $12 billion facility in Arizona.

In addition, President Biden on March 31 proposed a $2 trillion infrastructure plan that includes $50 billion to provide incentives for building new semiconductor facilities in the US, including a National Semiconductor Technology Center. The US Senate is considering a separate Chips for America Act that would provide $30 billion to build domestic semiconductor facilities.

Although it is too early to know whether Biden’s proposed plan will be adopted and in what form, analysts believe it could touch off a huge ramp-up in capital investments as companies take advantage of what is predicted to be a sharp increase in growth.

“Clear beneficiaries of an infrastructure bill would be sectors sensitive to ‘picks-and-shovels’ capex,” says Savita Subramanian, a quant and equity strategist at Bank of America, referring to industrial companies and metal producers. In a note to investors, she added that the infrastructure bill is likely to boost capex because US equipment is aging, companies haven’t fully invested in technology and capacity utilization is rising to levels that normally come before accelerating capex, and also because of the “reshoring trend,” with companies like Intel moving facilities back to the US from abroad.

The other major area of capital investment is renewable energy. While investments in extraction industries have been cut back, there is a major global effort to encourage adoption of renewable-energy sources, with government subsidies helping private sector utilities and other firms rapidly increase their investments.

“It is not only demand for clean power, but after Covid-19 companies and governments want to build back better, so we are seeing a lot of momentum in the renewable space,” says Audun Martinsen, head of Energy Service Research at Oslo, Norway–based Rystad Energy.

Martinsen says he expects capex on renewables to reach $243 billion this year, growing at an annual compound growth rate of 17%. While wind turbines currently account for 650 gigawatts of installed capacity compared with 346 gigawatts of solar generation, Martinsen says solar is now receiving far more investment than wind and is expected to reach 743 gigawatts by 2025. The largest share of the renewable investments is taking place in Asia—in China, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines, he says.

Rob Subbaraman, head of Global Macro Research at Nomura in Singapore, says the renewable boom in Asia is being driven by government policy, with countries such as Singapore, Korea and China leading the way. “There will be a lot of incentives for the private sector, such as carbon taxes,” Subbaraman says. “There will be fewer and fewer incentives to do brown investments because of carbon taxes, and as the cost of pollution goes up.”

In general, Subbaraman says that the boom in capex is just starting to take shape in Asia, and he expected the trend to become clearer in the second half of the year.