A TOUGH ACT TO FOLLOW

By Denise Bedell

Investors are preparing for post-Lula life after Brazil’s drawn-out presidential election.

When Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took over as president of Brazil in January 2003, investors and the financial community feared that this relatively unknown leftist leader would drive the country’s economy into the ground. Instead, Lula has presided over one of the most remarkable and seemingly resilient economic revivals in recent history, winning admiration from left and right in the process. Now, after almost eight years as president, Lula is standing down.

With the explicit support of the man whom Barack Obama reportedly dubbed “the most popular politician on the planet,” Lula’s anointed successor, Dilma Rousseff, should have been a shoo-in. Instead in the early October election she failed to gain the 50% of the vote needed for her to secure the presidency, forcing a run-off election race and leaving Brazil—and the wider Latin American region—facing yet another month of uncertainty. Even before the election, concerns were being voiced that Rousseff might not be able to fill Lula’s exceptionally big shoes. After her failure to clinch the presidency in the first round, those concerns only deepened.

As this edition of Global Finance was going to press, Brazilians were preparing to vote in the run-off election that Rousseff was, once again, expected to win by a wide margin. But while the election result was still up in the air, the likely impact on investors within Brazil and in the region as a whole was becoming clearer. Whichever way the run-off plays out, the impact on Brazil’s foreign investment policies will likely be minimal.

This is a far cry from the market fears that arose during the 2002 presidential election, when da Silva took power, and is a clear sign of how Brazil’s economic and market policies have developed in the interim. In fact, leading up to the elections this month the Eurobond markets were quite active, with a number of big international deals done by Brazilian companies pulling in strong demand from global investors.

Part of the reason for the relaxed attitude among foreign investors is that the key economic policies of the two rival presidential candidates—Rousseff of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) and José Serra of the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira—are remarkably similar. Stephen Hood, a São Paulo–based partner in law firm Mayer Brown, says: “There is not a huge difference in policy between the two.” The most important concern for foreign investors, according to Hood, is that the economic fundamentals in Brazil remain strong. “This is a result of the economic policies adopted from the mid-’90s onward by the government that was in power before the PT under Lula,” he says.

Stark Differences

The economic environment in which this year’s election was held could hardly be more different than the feverish period in 2002 when da Silva won the presidency. At that time, the region was on tenterhooks. Argentina was in the throes of a devastating economic collapse, and concerns abounded that its neighbors, including Brazil, would be affected by contagion. Brazil itself was facing some serious challenges, and da Silva rode in on a platform of social change. This time around, Brazil’s economy is in robust good health and is the darling of many international investors.

Yields on Brazilian government bonds clearly illustrate the story. In 2002, prior to the election, they soared as high as 33%. That compares with current yields hovering around 11%, depending on maturity. In addition, foreign exchange reserves in 2002 dropped to just $37 billion, whereas now they stand at close to $300 billion. Brazil is now a net creditor as opposed to a net debtor—which it very much was in 2002.

Contrary to many market watchers’ and analysts’ expectations, da Silva and the PT proved a remarkably stabilizing influence on the country. “The PT didn’t really change the policies that tamed inflation, and they continued the huge privatization program. It was very significant that the PT didn’t really change the macro policies after winning in 2002,” Hood says.

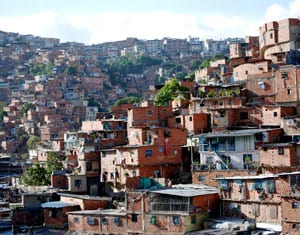

In addition to maintaining the positive market and fiscal programs begun before it assumed power, the PT also introduced a number of social policies that set in motion the rapid development of a strong middle class within Brazil, which provided a solid backdrop for the massive growth seen in Brazil over the past few years. It established, for example, the Bolsa Familia—a country-wide stipend for poor families that was part of a broader set of social policies passed during its two terms in office. Rather than merely draining federal money, the stipend has acted as an economic stimulus, according to market watchers. Establishing a solid domestic economy has not only driven demand and growth in Brazil but also helped insulate the country from shocks experienced worldwide during the economic crisis.

Whichever of the rival candidates becomes president in January, there is little fear of a turnaround in fiscal or monetary policy. From a foreign investment perspective, the elections and the run-off have had very little impact. Alfredo Coutiño, director for Latin America at Moody’s Analytics, says that the main economies in Latin America, including Brazil’s, have been flooded by portfolio investment, “given the still-attractive yield gap with respect to U.S. government bonds.” In fact, there has been a record amount of Eurobond issuance into the international markets so far this year. Hood points out: “There has been a terrific amount of activity, especially in the context of foreigners throwing money at Brazil.”

Two recent big bond transactions indicate the level of interest that most of the big corporate issuers have garnered. Telecoms company Telemar Norte Leste issued a $1 billion Eurobond, and steel company Companhia Siderurgica Nacional issued $1 billion in perpetual bonds. The CSN transaction will be used to redeem $750 million in perpetual bonds that the company issued in 2005, bringing the coupon down from 9.5% on the 2005 issue to 7% on the current deal. Telemar’s 10-year bonds will also be used to repay existing debt—outstanding notes set to mature in 2019 that were launched with a coupon of 9.5%. The new issue was increased from $750 million and has a much lower coupon than did the earlier bonds—at just 5.5%. Indicative of investors’ attitudes to Brazil is the fact that both issues were heavily oversubscribed.

If anything, Brazil’s policymakers are trying to rein in the amount of investment flooding the economy, not least because the new money is driving up the value of the real. The country’s finance minister, Guido Mantega, announced early in October that a financial transaction tax on foreign investments would be doubled to 4%. The tax hike applies specifically to fixed-income investments made by foreign investors—equity and direct investments are as yet exempt.

A Mixed Picture

Not all indicators are positive for Brazil. Between 1995 and 2009, for example, its GDP per head grew at less than a third of the rates of India and China, according to IMF statistics. And a number of market watchers have highlighted concerns over potential inflation as the currency continues to rise. Petya Koeva Brooks, division chief of world economic studies at the IMF, believes the government has responded well to inflationary pressure, though. “The central bank raised interest rates by about 200 basis points,” he says, “which we think was the appropriate response.” Plus, it is difficult to ignore the significance of Brazil’s growth story. Brooks says: “In the first half of this year it was growing at over 8%. For the year as a whole we are seeing growth at about 7.5%. Any economic slack that was there seems to have been exhausted.”

While Brazil’s prospects appear good, concerns remain for Latin America as a whole. Coutiño explains: “There are still a few countries using fiscal and monetary policies with a certain indiscipline, which gives a short-run benefit for growth but imposes serious risks for the economy in the medium and long term.” He is also anxious about recent noneconomic developments. “Criminality and delinquency have risen in basically the main economies, particularly in Brazil and Mexico, and the less-developed nations, which at the end might start to impose limitations to foreign investment,” Coutiño adds.

|

|

The favelas or slums belie Brazil’s rapid pace of economic growth |

Regional economic growth is expected to be strong throughout the rest of 2010, although it may slow somewhat into 2011 as global growth tails off. But countries with substantial domestic demand—including Brazil, Peru, Argentina and Chile—will continue to be active, dynamic markets. Those countries that are highly export-driven, such as Mexico, will feel a greater effect from any external slowdown.

Currency Rises Fuel Inflation Fears

The strong growth in many countries has led to some currency appreciation that must be actively managed in order to deal with potential inflationary issues. This is exacerbated by countries, such as China, that are using monetary policy controls to keep their currencies relatively undervalued, making international goods more expensive from those countries with strong currencies, as is the case in a number of Latin American countries. This has led to talk of a potential global currency war, with countries using monetary controls to affect the cost of goods. Should this happen, it could be devastating to Latin American countries that depend on exports.

Colombia and Paraguay are examples of how the strength of the region is creating opportunities that international investors are keen to take advantage of. Both have seen exceptional growth—Paraguay, in particular, is seeing its highest growth rate in 30 years—and are taking advantage of the strong global demand for natural resources and agricultural products. Foreign direct investment in Colombia is expected to hit $10 billion this year.

And, as with Brazil’s election, national elections this year in Chile and Colombia have been reassuring from an international investor’s perspective, as they enhanced the stability of economic policies within those markets.

A sign of the growing confidence regionwide is that bank lending in Latin America’s main markets is once again increasing in response to strong economic growth, which is helping to sustain domestic demand figures. Many countries are seeing strong growth in infrastructure development on the back of this.