The demographics of Caribbean investor-citizens changed as their numbers grew during the pandemic.

Five Caribbean countries found in their citizenship-by-investment programs (CBIs) a lifeline as the pandemic ravaged their economies.

Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Dominica and Grenada saw their programs run full steam throughout the year and a half of the pandemic so far, securing much-needed cash.

“Our application numbers have been astonishing,” says Nestor Alfred, CEO of the Saint Lucia CBI unit. “This year has been absolutely the best year for us applications-wise.”

The profile of applicants changed too. Caribbean CBI programs historically attracted mostly citizens from emerging nations. Since the pandemic, however, data from CBI specialist Henley Global shows a 204% surge in applications from US citizens, with strong growth also in applicants from Canada (47%), Australia (41%) and Britain (31%). “Investors from emerging and developed economies alike are seeking out alternative business, career, educational and lifestyle opportunities on a worldwide scale,” says Dominic Volek, group head of private clients at Henley Global.

Saint Lucia and Grenada have been the biggest winners, posting record-breaking numbers during the crisis, according to Investment Migration Insider (IMI). But the business has been thriving in all five nations, with outsized impact.

“Because both GDP and government revenue are down drastically due to the reduction in tourism,” says Christian Nesheim, IMI founding editor, “the relative importance of CBI on GDP is certainly higher in 2020-2021 than in 2019.”

The global CBI industry, now running at around $25 billion a year, is powered by high and ultrahigh net worth individuals who wish to enhance their global mobility and diversify tax jurisdictions. Caribbean CBIs are among the most accessible—a relatively good value offering not only tax-free environments but visa-free access to Europe’s Schengen Area, a visa-free zone of 26 European countries; and in some cases Russia, the US, Canada and China.

“Sovereign states need capital, and investors are worried about their assets falling in value. The parallel with 2008 is clear,” says Volek.

Some regulators outside the Caribbean, such as the European Council (EC), have raised concerns that CBI programs could be used for tax evasion. In February, the EC added Dominica to its list of noncooperative tax jurisdictions as it was not rated “largely compliant,” as required. but only “partially compliant.” Criticism of Dominica’s CBI program was also leveled by the Arabic media giant Al Jazeera, who in 2019 accused the country of aiding international money laundering via the sale of diplomatic passports.

Internally, however, support for CBIs is much greater. “The programs bring employment and unencumbered government revenue,” explains Nesheim. “The latter ensures the government doesn’t need to borrow money or raise taxes to fund its operations or various Keynesian aid schemes, like social housing or airports, which tend to have broad popular appeal.” He adds that in the CBI-offering islands of Malta and Cyprus, however, “opinions are much more divided on the issue.”

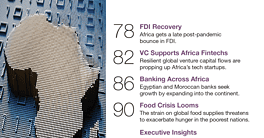

Travel restrictions and personal cautionwill likely continue to dampen tourism, so social programs remain vital. With a new hurricane season underway and climate change threatening worse, Caribbean governments are counting on CBIs to support climate resilience. “Hurricanes do cause extensive damage to the islands,” says Volek. “[Islanders] look to the funds raised by CBIs as a lifeline for recovery and relief.”