China, Russia and India vie for dominance in Africa in the new Great Game.

From an African perspective, the Western alliance’s withdrawal from Afghanistan is not so much a question of lost prestige as of future commitment. Can the US and its allies still be seen as reliable partners? Especially compared to the “new” big-time players—China, India and Russia—whose fast-expanding presence across the continent and intense rivalries at times resemble the 19th century scramble for Africa between colonial powers.

This blow comes hot on the heels of the Covid-19 pandemic, during which most Africans have been denied access to vaccines because wealthier countries hoovered up global supplies and big pharma refused to license production locally. Where precisely is the moral high ground in that?

While US President Joe Biden is declaring “America is back,” African leaders are increasingly looking elsewhere. In April, South Africa turned to Russia and China to relaunch its national vaccination campaign after finding the Oxford/Astra Zeneca vaccine less effective against a local variant of Covid-19. Starved of Western supply, many other African countries took the same route.

“What’s happening in Africa right now is a Western failure, and therefore presents an opportunity for Russia and China,” says Paul Goble, a veteran observer of the post-Soviet space for the Jamestown Foundation. “The Russians are milking it as part of their anti-Western propaganda.”

As an important vaccine producer, India was one of the first movers in a UN-backed global Covid-19 response, earning respect across Africa. “For India, the pandemic presented an opportunity to demonstrate its willingness and capacity to shoulder more responsibility,” says Abhishek Mishra, associate fellow of the Strategic Studies (Africa) Program at New Delhi’s Observer Research Foundation. “Under the Vaccine Maitri initiative, we supplied 24.7 million “Made in India” Covid-19 vaccines and COVAX supplies to 42 countries in Africa.”

However, due to the deadly surge in domestic cases last May, the Indian government decided to halt all vaccine exports. “Of course, this badly affected Africa’s mass vaccination drive,” says Mishra, after it was already lagging. “The ban did not bode too well for India’s image in Africa,” Mishra admits, even though previously its approach of stressing a South-South partnership and focusing on core competencies such as IT, capacity building, human development and homegrown techniques for soil and water management probably gave it more bang for its buck than other players in Africa.

Another advantage over Western governments and multinationals—whose engagement in some African countries is circumscribed by human rights or ESG concerns—is that India has adopted a less confrontational approach, which Mishra summarizes as: “No conditionality, no prescriptions and no questioning of sovereignty.” Such respect for existing political regimes is likewise a hallmark of Chinese and Russian relations with African states.

“Washington consensus–based multilateral institutions attach conditionalities to their loans to countries, including democracy, human rights and environmental standards,” says Shirley Yu, director of the China-Africa Initiative at the London School of Economics and a senior practitioner fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School. “When Chinese institutions loan to countries, few conditionalities are attached.” She expects China to increase environmental conditions as part of fighting climate change, but not political conditions.

“African countries,” she says, “almost all of which rely on an investment-led growth model, have a choice today between Chinese-originated loans and Western-originated loans.” And it is clear where this is leading. While the United States, France and the United Kingdom retain the biggest existing stocks of foreign direct investment in Africa, Yu notes “China surpassed the United States in 2013 as the largest FDI originator and we have witnessed a consistent net US FDI outflow in Africa.”

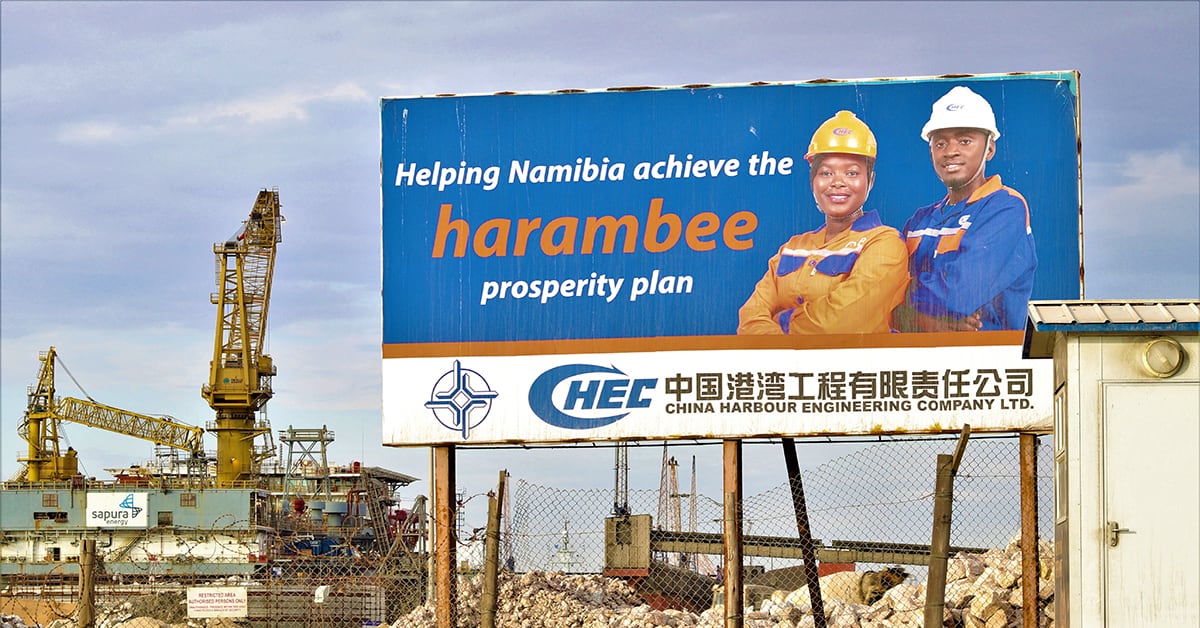

Unlike its main competitors, China’s engagement in Africa is governed by long-term strategic considerations supported largely by public enterprises: ensuring resource and food security, as well as improving access to communications and infrastructure.

“Infrastructure connectivity induces not only economic growth opportunities, but a strategic common destiny under the auspices of China’s Belt and Road Initiative,” Yu explains. “China is responsible for one-third of Africa’s power grids and has stakes in 46 port projects in Africa, with various models of financial/operational partnerships. These large-scale infrastructure investments, with high-risk and long-term return potential, can only be undertaken by entities owned by the Chinese state.”

China’s carefully directed investments include East-West transcontinental railways that promise to enhance inter-African trade and development for land-locked countries—especially once the AfCFTA free-trade measures (of which China was a forceful proponent and is likely to be the main beneficiary) take effect. All of this requires huge funding, and China established multilateral financial institutions, including the AIIB, the New Development Bank and state policy banks such as EXIM Bank and China Development Bank, to provide the necessary loans—often at preferential rates.

“With a deliberate whole-of-government approach to support China’s Belt and Road Initiative in place, it is very hard for Western countries to compete,” Yu argues, “based on the level of financing and the willingness to invest in virgin markets.”

It is even harder for the other new players, Russia and India, which have more limited financial resources. While Putin’s hosting of the first ever Russo-African summit at Sochi two years ago might conjure up hopes of a return to the 1965-1989 heyday of Soviet influence in Africa, Russia lacks both a clear strategy and the resources. Its own economy is less than a sixth the size of China’s, its trade with Africa only a tenth and its investments in Africa’s long-term infrastructure are minimal.

By contrast, India’s trade with Africa currently stands at $70 billion, which Mishra says makes it the third-largest trading partner and Africa’s fifth-largest investor, with some $64 billion of FDI. It is also one of the largest contributors of troops to UN peacekeeping operations across the continent and supports antipiracy and maritime security operations along Africa’s coastline with the Indian Ocean.

With its engagement focused on South Africa—where there is a large and influential Indian diaspora—and the continent’s eastern seaboard, India’s strategic priorities remain defensive and in direct competition to Chinese expansionism. “India’s main concern,” says Goble, “is to ensure that the Indian Ocean does not become a Chinese lake.”

Given the closer relations between China and Russia in recent years, their shared anti-Western stance and increasing authoritarianism, it might be expected that they might cooperate more closely in Africa. So far, that has not been the case. “China and Russia are clearly not working together,” says Goble. “Instead, their actions are often at cross purposes—as in Russia’s courting and military support of Sudan, Eritrea and Somaliland to enable a naval base near the Red Sea’s chokepoint, which could conflict with China’s military base established in 2017 at Djibouti.”

Russia’s engagement in Africa is largely based on arms sales and the provision of security services through state-owned groups as well as private military companies (PMCs) like Wagner. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Russia accounted for nearly 38% of all arms sales in Africa between 2015 and 2019, ahead of the US (16%), France (14%) and China (9%). Often using Wagner as its agent on the ground, Russia has intervened in politically unstable countries like the Central African Republic and Mali, and in return gained control of mining concessions.

“For Putin,” says Goble, “Africa provides an array of opportunistic targets where quick gains in terms of winning political influence can be made in precisely those areas where other players are pulling back.” However, Goble is not convinced there is any longer-term strategy to it than “a string of foreign-policy victories over the West that help boost his domestic ratings.”

Unless something changes soon, Goble is convinced that “China will be the paramount power in Africa by the end of this decade.” Given US reluctance to engage in further military adventures overseas, the only means for other players to compete with China is through closer cooperation.

“There is immense potential here for India, the European Union and Japan, along with the UAE.” says Mishra. “We have announced the Asia Africa Growth Corridor initiative with Japan, and there is huge potential of an EU-India-Japan trilateral in Africa, especially in the areas of maritime connectivity and digital financial inclusion.”

“The EU, Japan and India can combine their respective strengths: the EU’s resources and its diplomatic and economic presence, Japan’s large infrastructure capabilities with a thrust on quality and budgetary leeway, and India’s diplomatic legacies along with its human resource capacity,” Mishra argues, “Taken together, these hold vast potential that could be leveraged through further cooperation in Africa.”