The fintech sector is heating up across sub-Saharan Africa. Foreign investors are paying close attention and providing start-ups with the capital needed to get off the ground.

On the African continent, 80% of the people are unbanked. This is the highest ratio in the world and puts the banks in a unique position. In recent years, new technologies—especially mobile phones—have enabled financial actors to close the last mile and finally reach these populations.

Africa is also home to seven of the world’s fastest-growing economies, representing a significant opportunity for start-ups to provide new financial services to people who never experienced financial inclusion previously. In 2016, the number of financial technology start-ups securing investment increased by 84% compared with the previous year.

African fintech solutions are very different from their counterparts in the rest of the world. In some cases, they even allow clients to leapfrog from the cash economy to the future of banking.

Africa was essentially a cash economy until telecom operators introduced mobile payments in the 2000s. The regional mobile-wallet champion is undeniably Kenya’s M-Pesa, launched by a Vodafone affiliate in 2007. Today, half of the Kenyan population has an M-Pesa wallet, and the volume of transactions on the platform is equivalent to 50% of the country’s GDP. Worldwide, the service operates in 10 countries with over 30 million active users.

Following this Kenyan success story, other mobile operators across the continent launched similar services, like MTN Mobile Money or Orange Money. By 2016, there were 277 million registered mobile-money accounts in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with only 10 million in Europe and Central Asia.

The drawback for banks is that this new business model ties them to the telecom operators. To meet this challenge, some start-ups have developed technologies that allow digital banking to be independent from mobile operators.

Such is the case with TagPay, a mobile-banking platform that uses audio technology to secure mobile transactions. Started in 2005, the company now operates in 15 African countries and processes about $300,000 worth of transactions daily.

“The bank we have in Africa is not a new African bank; it’s the future of banking everywhere in the world,” says Yves Eonnet, co-founder and CEO of TagPay, “and it starts in Africa.”

TagPay doesn’t see traditional banks as the enemy. On the contrary, the company has partnered with 25 banks on the African continent, and last year France’s Societe Generale even acquired a minority stake for €1 million ($1.1 million).

“Working with large banks, following their audits and compliance, makes us more trustworthy and credible to everyone,” says Eonnet. “For the banks, working with us gives them agility.” He cites the example of a bank that needed to distribute UN subsidies to 600,000 farmers, and wanted to avoid cash, so TagPay developed a whole new system—in just three weeks. “The farmer received an SMS [text message], went to the store, [and] made a secure transaction with his phone. The merchant got paid instantly, and the farmer went home with his bag of crops,” Eonnet says. “A few years ago, this would have happened with trucks filled with bank notes running from village to village.”

Another fintech opportunity for African start-ups is in remittances. According to World Bank figures, the continent attracted $62 billion worth of remittances in 2015, compared with $55 billion in foreign direct investment and $50 billion in foreign aid. In other words, remittances are the biggest source of foreign investment in Africa. Sending money to Africa, however, is substantially more expensive than sending it anywhere else. The average cost of a transaction into the continent is 12%, and for some money transfers between African countries, the rate can be as high as 25%.

How can one make it easier and cheaper to send money back home? One of the solutions put forward by African entrepreneurs is the “cash-to-good” service. Instead of sending cash, users can remotely buy goods and services for their families. Mergims is one of these start-ups. Based in Rwanda, it allows users abroad to settle their relatives’ bills, pay school tuition or buy gift vouchers.

“We can literally onboard any type of business. Merchants just have to register and use our APIs or our automated voucher generator system,” says Louis-Antoine Muhire, co-founder and CEO of Mergims, which is now looking to raise $500,000 in Series A funding. Where Western Union and MoneyGram charge service fees of 12%, on average, Mergims takes only 5%, and the system ensures that the money is spent on the targeted purchase. Launched in 2015, the start-up now has 2,500 monthly active users and $100,000 worth of transactions. It plans to expand into Ghana in November and Benin in 2018.

Cash-to-good has inspired other start-ups, such as Yenni in Senegal, which allows the diaspora to finance health insurance for loved ones back home, and France-based Afrimarket in Western Africa.

African fintech firms also target more complex financial services, such as loans, credit lines and wealth management. New data-driven technologies allow entrepreneurs to collect unique information about their users, and in some cases to estimate the solvency of a client to decide whether to extend a microloan.

This is exactly the business Branch is tapping into. Its application analyzes the data stored in users’ phones to determine if they could be good borrowers. If yes, then Branch can open a credit line from $2.50 to $500 in 10 seconds. Based in San Francisco, the start-up just raised $9.2 million in Series A funding, led by Silicon Valley venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

In wealth management, technology adapts to tradition, as in the case of South African Livestock Wealth, which allows users to invest in cattle.

An Ecosystem Yet To Emerge

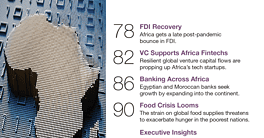

In the past two years, African fintechs have raised over $100 million in investment from local and international investors. Recent success stories include digital payment solution Flutterwave, which secured over $10 million in a Series A round led by Greycroft Partners and Green Visor Capital; and South African mobile wallet Zoona, which raised $15 million.

However, unless investors show substantial interest, it is still very difficult for African entrepreneurs to secure funding. “In Europe or in the United States, there is a complete ecosystem with accelerators, funds, business angels ready at every stage of a company’s growth,” says Laurent Demey, a partner at private-equity fund Amethis Finance. “In Africa this is not the case. There are funds but it is not enough, especially at seed stage.” Amethis plans to pump €280 million in equity and $150 million in debt into long-term investments in sub-Saharan Africa.

“With time, the ecosystem will develop around regional hubs like Nairobi or Lagos but the continent remains very fragmented,” he adds. “Each one of the 54 African countries is a different market, and that is a real challenge.”

For now, investors look essentially at Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa. In 2016, these three countries attracted more funds than all the other African countries put together but that is likely to change as the continent continues its digital transformation. Telecom watchers predict that in only three years, there will be 300 million more smartphones in sub-Saharan Africa.