A nascent global recovery is improving prospects across Latin America and the Caribbean—albeit unevenly.

Good news from Latin America: With Brazil and Argentina coming out of the 2015-2016 recession, the region has returned to expansion mode and is expected to gain economic strength this year and next. The return of capital inflows and an apparent change in foreign direct investment (FDI) are the most evident signs that investors’ views of South and Central America have tilted more to the positive of late. The region is back on track.

A world economy in which all major developed economies and China are expanding has put an end to the four-year slump in commodity prices. Copper, oil and soy prices did well in the past months, giving strength to key export markets for countries such as Chile, Colombia, Brazil and Argentina.

“This seems to be a year in which economic conditions are right for Latin America,” says Alejandro Werner, director of the Western Hemisphere department at the International Monetary Fund, presenting in January the latest IMF estimates for the region. The IMF sees a 2.5% increase of GDP in 2018 for Latin America (excluding Venezuela) and the Caribbean, up from estimates of 1.9% in 2017 and 0.1% in 2016.

At the same time, FDI flows to the region were up by 3% from 2016 to 2017. It was the first increase in five years, and is still 25% below the level reached at the peak of the commodity boom in 2012, according to the January Investment Trends Monitor from UNCTAD.

“I would expect FDI to change trend as economic growth [revives],” says Juan Manuel Ruiz, chief economist for South America at BBVA. “Two important drivers of FDI in Latin America are the domestic markets, which have already improved, and commodity markets that have bottomed out. Both these factors are going to remain positive.”

Marcelo Carvalho, head of emerging-market research for Latin America at BNP Paribas, concurs. “We believe the major players in Latin America are already in an upswing,” he says. “Since 2016, there has been a marked shift of mood across the region, as Brazil, Argentina and Chile have been shifting gears to more-market-friendly policymakers, with potential for stronger fundamentals ahead of the implementation of reforms. Foreign investors have an eye on that, which was reflected in an improvement in investment flows throughout last year.”

Can the region maintain this positive momentum? Caution remains mandatory in an area where a single country, Venezuela, wiped out almost 50% of its GDP in the last five years. An extremely busy political calendar may put at risk key reforms. In the months through the end of October, six Latin American countries—Costa Rica, Paraguay, Colombia, Mexico, Venezuela and Brazil—will hold presidential elections. Recessions, a burst of corruption scandals and severe inequality provide populist candidates a fertile ground for political success.

Powerhouse

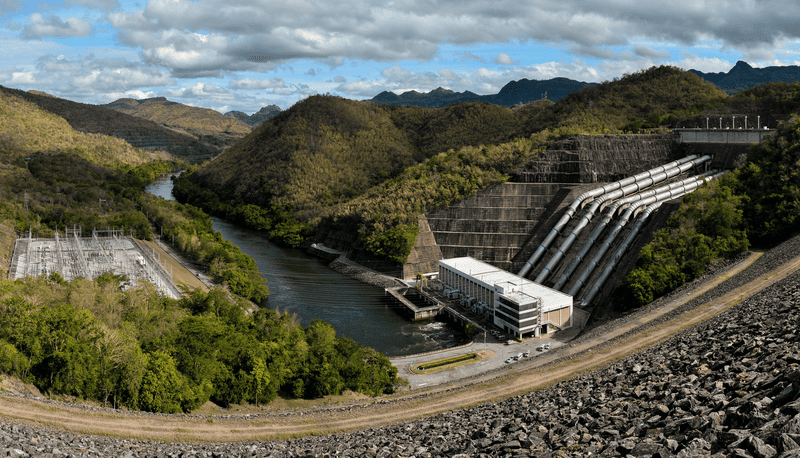

Latin America’s largest economy and the darling of international investors when commodity prices were soaring, Brazil has regained positive momentum. According to UNCTAD data, FDI increased by 4% in 2017. Around $20 billion came just from China, which is betting big on utilities: China’s State Power Investment Corp bought 30-year operating rights to São Simão hydropower plant for $2.2 billion last year. More recently, Chinese ride-sharing company Didi Chuxing acquired control of its Brazilian counterpart, 99.

At the same time, investors have been pouring funds into the equity market.

“The big story of the last six months in Latin America has been the portfolio inflows, for Brazil [specifically] but also for all Latin America,” says Neil Shearing, chief emerging-markets economist at Capital Economics. Brazil’s Bovespa accumulated more than 40% in the last 12 months, he notes, and got “an extra shot in the arm” from a recent court decision to uphold the corruption conviction of the former president.

Current market optimism stems from a string of positive macroeconomic data; but as time goes by, investors will likely focus more on the elections. The new government will face significant challenges. The country’s public deficit remains around 8% of GDP, despite a revenue rebound. Public pensions absorb about 12% of GDP.

Politics

Mexico, also one of the region’s larger economies, will pick a new president on July 1. Political uncertainty will mix with doubts arising from ongoing negotiations on the North American Free-Trade Agreement (NAFTA) among the three parties: Canada, Mexico and the US.

“NAFTA has been a platform for integration of the three economies that goes beyond trade; it makes the economies more powerful,” says the IMF’s Werner. “Since Mexico is the smallest and least developed economy [of the three], it is also the one that benefits most from this partnership.”

Talks, which started in 2017, could drag on for months, even into 2019, with the possibility that final negotiations will be undertaken by a new and totally different administration. Andrés Manuel López Obrador, better known as AMLO, is expected to make a good showing. A former Mexico City mayor who narrowly lost the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections, he represents the National Regeneration Movement (Movimiento Regeneración Nacional, or Morena). His anticorruption, anti-Trump, pro-human-rights positions have so far been very popular.

The powerful Institutional Revolutionary Party (Partido Revolucionario Institutional, or PRI), which held the presidency for 70 years up to 2000, and from 2012 to today, will be represented by José Antonio Meade Kuribreña, who was finance secretary until last November. An independent economist with a doctorate from Yale and a background on the Board of Governors at the World Bank, the EBRD and other development banks, Meade is one of the few members of the Peña Nieto administration who has not been involved in corruption scandals and is seen with favor by the business community.

So far, the market has looked at the July vote with some fear but general optimism.

Meanwhile, in Chile, the return of Sebastián Piñera, who won a run-off election in December, factored with a better outlook in the copper market to provide a noticeable improvement in growth perspectives. “For Chile, the increase in the price of copper has been very positive news that reflected on the currency market and prompted us to increase our GDP forecast by 0.3%,” says BBVA’s Ruiz. BBVA sees a GDP growth of 2.7% in 2018, up from 1.5% in 2017.

Colombia is also facing elections soon: on March 11 to elect new members of the Senate and the Chamber of Representatives; and on May 27 to select a new president. These elections, the first after the conclusion of the peace process with the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia), are considered historic; but the market has the highest confidence that market-friendly policies will be maintained by whoever is elected.

“We do not really foresee any major changes to the long pro-market political consensus in the country,” says BNP’s Carvalho. “We expect FDI in the country to improve this year, and especially in 2019, along with a gradual recovery in domestic demand, with the GDP one percentage point higher this year—at 2.5%—compared to 2017, and with the improvement in oil prices from 2015 and 2016.”

Latin America is back on the upward path, but its rates of growth still heavily underperform those of other developing economies. Peru tops the ranks for growth in the region, with a GDP increase for 2018 at 4% expected by the IMF.

“The region continues to struggle with respect to its medium-term sustainable growth,” says Werner. “They are struggling to find other sources of sustained growth.”