Oman qualifies as the least known and understood of the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, but its importance goes beyond its size.

The Sultanate of Oman, located on the southeastern shoulder of the Arabian Peninsula, faces several reckonings. Most immediately, it needs to diversify its economy so that the country is less dependent on oil revenues.

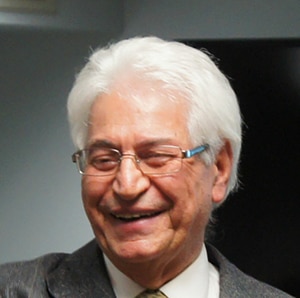

In fact, recent experience shows the country has little choice but to make economic changes. “The slump in oil revenues was not matched by a reduction in expenditures,” explains Lebanese-born Atif Kubursi, economics professor emeritus at McMaster University, former acting executive secretary of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia, and former consultant to the Omani government.

The International Monetary Fund has urged Oman to reduce its annual deficit to 5% of GDP from its current level of 21%. The government expects to reduce that deficit to 7% of GDP by 2023—an improvement, yet still short of the recommended threshold. Meanwhile, Oman continues to rely on external borrowing to cover its deficit shortfalls.

The situation is becoming increasingly urgent, in part due to falling oil revenue, but also because Oman’s oil reserves are lower than those of other GCC members. In March, Moody’s Investors Service downgraded the Oman government’s long-term issuer and senior unsecured bond ratings to Baa3 from Baa2 with a negative outlook. Baa3 is the lowest investment grade and one notch above junk bond status. In explaining its decision, Moody’s cited Oman’s weakening fiscal and external metrics, projected continuing weak growth, and large fiscal deficits.

Still, Oman’s economy ranks as one of the most stable overall in the GCC, Kubursi says, based on four pillars: oil and gas, tourism, fishing and traditional activities such as cottage industries. In fact, with the exception of Dubai—one of two core members of the seven-member United Arab Emirates (the other core member being Abu Dhabi)—Oman currently boasts the most diversified economy in the Gulf.

The expansion of its tourism sector—now averaging some 300,000 visitors per month—has had significant impact. Oman ranks second in the Arab world for societal safety and security, according to the Global Peace Index 2018 published by the Australia-based Institute for Economics and Peace. Tourism growth enabled the country to reduce the proportion of its GDP generated by oil from 44% in 2013 to 30% in 2017. The government can be expected to continue promoting its beaches, seashores and mountain vistas.

Ports—both maritime and air—will be a key to Oman’s evolution as a regional trade hub supporting logistics and manufacturing, which are top priorities for development, Kubursi explains. A consortium of Chinese companies called Oman Wanfang has pledged $10.7 billion to develop the Duqm Port and other projects.

Strategic location is a huge advantage for Oman. “Just stopping in Salalah or the new port of Duqm instead of going through the Strait of Hormuz cuts travel time, which, in turn, cuts costs,” explains Glen Ransom, senior analyst for Middle East and North Africa at Control Risks. Omani ports will appeal to shippers hesitant to go through the Strait of Hormuz, Ransom explains. Basing Gulf shipping and logistics operations in Oman avoids exposure to potential disruption of trade resulting from a closure of the strait in the event of rising tensions or military confrontation between Iran and the United States, or between Iran and Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Kubursi, McMaster University: The slump in oil revenues was not matched by a reduction in expenditures. |

Another positive step is the announcement by the Oman Drydock Company that it plans to get into shipbuilding as a logical extension of its current activities.

Oman is also attempting to boost employment and control expenditures, a difficult equation since it has traditionally held down unemployment by increasing employment in the public sector. Strategies have included tightening of visa restrictions on foreign workers. “If [employers] are not meeting the government quota for how many Omanis they hire, the government might take action—such as fines or not allowing employers to renew visas for foreign workers—until all requirements are meant,” Ransom explains.

At the same time, the government’s decision to postpone implementation of the 5% value-added tax until 2019 will slow the effort to strengthen the country’s weak financial situation. The reasons appear to include a lack of readiness combined with a strategic political calculation, Ransom explains. “Having done some efforts over the past two years to reduce allowances for government workers and reduce subsidies, it might have been just a more strategic calculation that we won’t throw that on top of this.”

Oman’s attempts at maintaining a positive outlook have several qualifiers. It has a historic role as quiet mediator, having acted as an intermediary between Saudi Arabia and Iran, between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates since their rift with Qatar, and between members and nonmembers of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries. However, Oman is actually an outlier in the Gulf Cooperation Council, given its religious, cultural, political and foreign-policy differences with other GCC members, explains Gerald Feierstein, formerly US ambassador to Yemen and principal deputy assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs, and currently senior fellow and director for Gulf affairs and government relations at the Middle East Institute.

Unlike the other member countries of the GCC, Oman is not a Sunni state. The majority of Omanis are Ibadis, a Muslim sect separate from the Sunni and Shia branches of Islam. And there are historical differences between Oman and the rest of the GCC, Feierstein points out.

Historically, the Omanis have always been a seafaring mercantile nation, unlike the desert tribes that originally ruled what are now Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. At one time, its empire stretched into Africa as far as Zanzibar and included parts of what are now Pakistan and Iran. Oman consistently maintains an outward focus. Moreover, Oman has kept closer ties with the United Kingdom in the postcolonial era than other countries in the region; and unlike the other countries, it has not joined OPEC.

“The major issue right now is the fact that Oman has a close and positive relationship with Iran, while trying to maintain a neutral position in the inter-GCC dispute between Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar,” Feierstein explains.

Meanwhile, unconfirmed but regular reports suggest that arms are being smuggled from Oman across the border into Yemen to the Houthi fighters there. If these reports are accurate, it would further strain Oman’s relationships with Saudi Arabia and its allies—including the US—who are fighting the Houthi.