Serbia has paid a price to stabilize its finances, but found success.

Serbia’s history can appear difficult to follow, especially given its interactions with other countries in the region. But the past explains the present delay in joining the European Union.

Until the Balkan wars of the 1990s, Yugoslavia housed eight separate jurisdictions. In February 2003, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia became the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. Montenegro declared its independence in June 2006, and Kosovo followed in February 2008. The International Court of Justice in The Hague upheld those declarations as legal in July 2010, but Serbia continues to claim Kosovo. Its accession into the EU is contingent upon resolving this dispute.

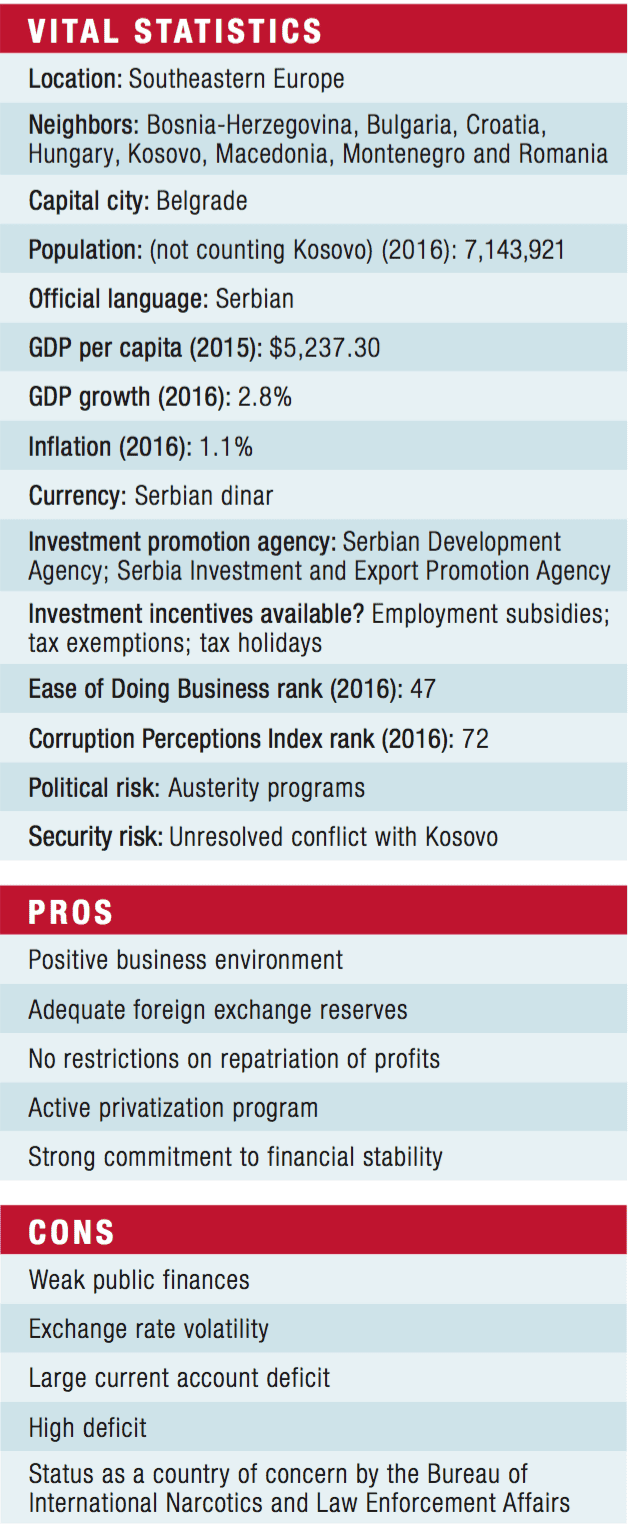

In the meantime, Serbia is working to take its place on the world economic stage, and much of that effort involves attracting foreign direct investment. “There is a strong incentive to attract foreign capital,” says Novak Jankovic, an economist familiar with Serbia. The government’s reform program focuses on ensuring economic and financial stability, halting further debt accumulation and creating an environment for economic recovery and growth to raise living standards. Presently, the Serbian government and Chinese companies are negotiating a takeover of Rudarsko-topionicarski basen Bor (RTB Bor), a copper mining and smelting operation.

Serbia offers several advantages for foreign investors, including stability and a recovering economy aided by austerity measures. “The last few years helped,” Jankovic says, explaining that the measures came at a high cost: cutbacks in pensions and government employee salaries. The measures also included improvements in tax collection and public finances.

Yet Serbia experienced limited backlash against these moves. “I would call that a success, for a country to go through such a strong fiscal consolidation and still maintain its political and social stability,” he says. “There was a growing realization that there is no other way, and the population proved its maturity or awareness.”

Serbia also offers low-cost labor and a corporate tax rate of 15% compared with the 20% more typical in other countries of the region. When Serbia joins the EU, it will provide a tariff-free platform for export to other EU countries. Its need for increased capital flows leaves foreign investors in a strong negotiating position, and the Serbian government budget reportedly has set aside cash reserves for stimulating foreign investment.

Meanwhile, since Serbia has not yet joined the EU, it doesn’t have to comply with restrictions such as the sanctions on Russia. This means that exports into Russia remain feasible; a strategy that Fiat, for example, uses to its advantage.

Several risks confront the investor, however. Serbia’s small size and population leave it vulnerable to swings in the world economy, and the Serbian dinar fluctuates against other currencies—a problem that confounds financial calculations.

Meanwhile, several questions overhang FDI decisions, including whether the population will continue to accept austerity measures, the influence of Russia on some of its neighbors and unclear American foreign policy toward the region.

For more information on Serbia, check out our Country Economic Reports