GCC nations are constantly recalculating the cost/benefit ratio of maintaining the dollar peg. Lately, external pressures give the question new urgency.

What are the merits and limits of the nearly GCC-wide currency peg to the dollar in a low-oil-price environment? Experts are divided and debate continues. With their economic cycles out of sync with the US, the oil-producing countries of the Arab Gulf are under growing pressure to break the dollar peg so they can lower interest rates and stimulate economic growth.

“Maintaining a peg has its costs, including loss of monetary policy flexibility,” says M.R. Raghu, head of research at Kuwait Financial Centre (Markaz) and managing director of Marmore Mena Intelligence. “If the GCC countries follow the direction set by the Federal Reserve, they will sacrifice their growth, as they will have to tighten monetary conditions during a period of low oil prices.”

Kuwait abandoned its dollar peg in 2007, in favor of linking its dinar to a basket of currencies, including the euro and the dollar. The change was motivated by the need to curb inflation at a time when the US currency was in a prolonged decline.

Now, with oil revenues down sharply, the GCC governments have less money to deposit in banks, which implies less lending capability and lower overall growth, Raghu says. The Saudi Arabian Monetary Agency (SAMA) estimates that for every 100-basis-point increase in the Saudi Interbank Offered Rate, there will be a decline of 9 basis points in gross domestic product in the subsequent quarter, and 9.5 basis points in the quarter after that.

“There is always informed discussion about the dollar peg for GCC currencies and whether this will be removed or not,” says Philippe Ghanem, vice chair of ADS Securities in Abu Dhabi. “The peg, so far, has been maintained as it provides an important hedge and allows volatility to be managed more effectively.”

Since most of the GCC countries have large foreign exchange reserves and are turning to the debt markets to fund fiscal deficits, the direct impact of lower oil prices on economic activity has been absorbed to some extent, Raghu says. Oil prices have rebounded from the lows seen earlier this year. But if relatively low prices persist, this could have repercussions in the future, he adds: “Looking ahead, all options are on the table. The countries could either continue with their current peg, or peg at a new level, or de-peg altogether.”

Fiscal Discipline Opens Doors

Jason Tuvey, Middle East economist at Capital Economics in London, says: “Devaluation will be the very last resort for Saudi Arabia, which has cut spending and made progress on fiscal consolidation. The authorities have made more progress in tightening fiscal policy than we thought was likely by this stage.”

The kingdom cut spending by 14.5% last year, with a similar drop penciled in for this year, Tuvey says. Meanwhile, reform of the subsidy system has begun, and gasoline prices have risen. Taxes on soft drinks and cigarettes are planned.

“These measures are a positive first step and should help to rein in the kingdom’s twin budget and current-account deficits,” Tuvey says. “In turn, the depletion of the country’s foreign exchange reserves should slow, and we maintain our long-held view that the riyal’s peg to the US dollar will remain intact.”

Jan Dehn, head of research at Ashmore Group, an investment manager focused on emerging markets, sees little reason to be worried about Saudi Arabia’s economy, in part because the Saudis have succeeded in adjustment measures and reforms. “They are not living hand to mouth,” Dehn says. “It is extremely unlikely that the dollar peg will break.”

Because Saudi Arabia used the past decade’s “go-go years” of high oil prices to pay down debt, Dehn explains, it now has one of the lowest debt levels in the world. “The Saudis know how to manage the ups and downs in the oil market, and this is just a macroeconomic adjustment,” he says.

Benefits Of Currency Stability

A stable currency softens the blow for consumers from rising prices in a region where almost everything is imported. Most of the adjustment in the dollar has already taken place, and the currency is stabilizing, according to Dehn, and with commodity prices beginning to drift higher, he believes “most of the pain for the GCC is behind it. “However,” he cautions, “the Iranians will pump oil until they are blue in the face, and shale oil producers will come back, so we are not going to see oil prices go a lot higher.”

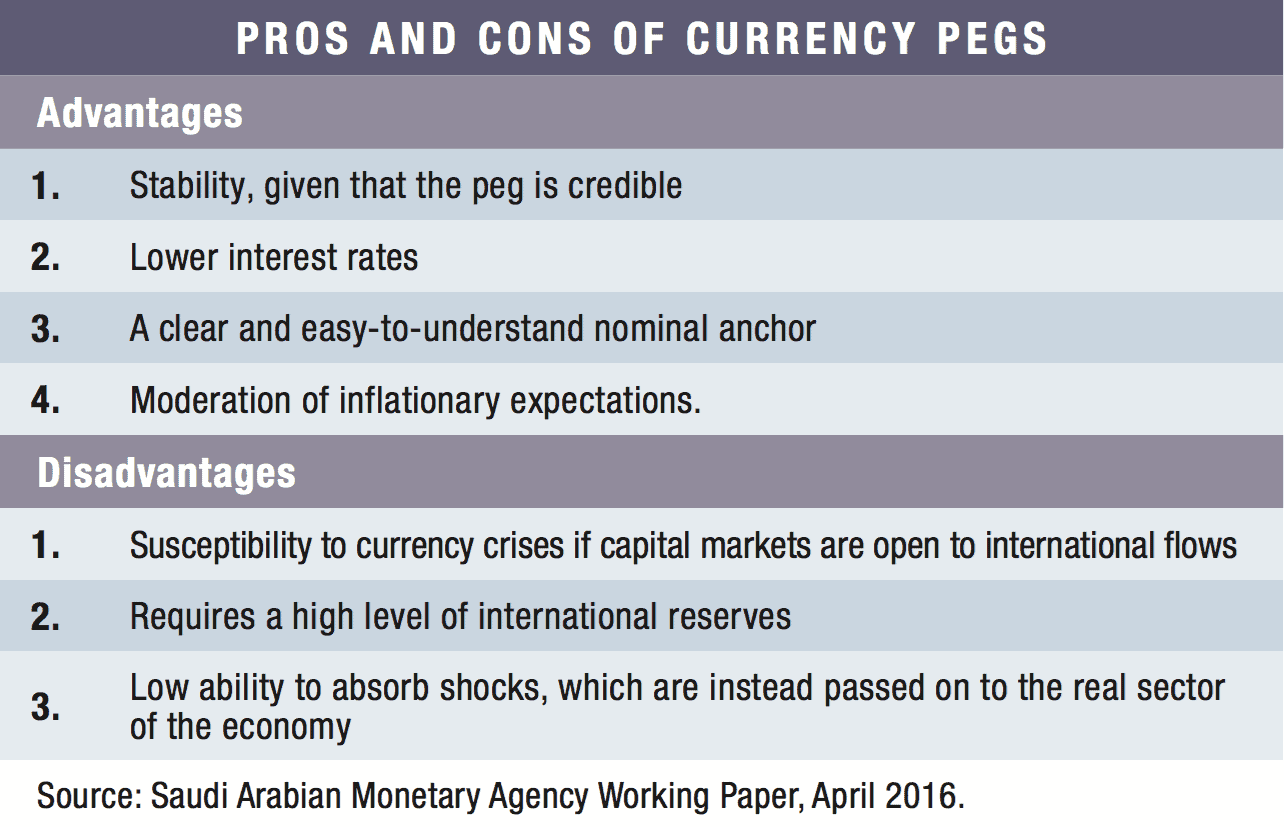

Researchers at SAMA, the Saudi central bank, examined various exchange-rate regimes that have emerged since the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement, focusing on the advantages and disadvantages of each. They concluded in a working paper released in April that the dollar peg has served Saudi Arabia well and is likely to continue to do so until the kingdom “becomes a meaningfully diversified economy, with exports denominated in a mix of currencies.” The paper was released on the day that powerful deputy crown prince Mohammad bin Salman announced the Vision 2030 reforms to ease the country’s dependence on oil.

Since 1986 the Saudi riyal has been tightly pegged at 3.75 to the dollar. In the SAMA paper, authors Ryadh Alkhareif and John Qualls conclude: “If we look at the arguments for a more flexible currency, it becomes apparent that most of them do not apply in the case of Saudi Arabia. The possibility of real shocks causing high real exchange rates is not particularly disturbing, since an overvalued riyal is not likely to harm the kingdom’s exports, which are denominated in dollars.”

The paper notes there has been much speculation about the desirability of a devaluation of the riyal against the dollar as a way to balance the budget. However, because such a move would raise import costs, the paper argues that “it would be much better to restrain government spending, raise non-oil revenue and borrow the funds necessary to close the revenue-to-expenditure gap.”

At the time the paper was published, Ahmed al-Kholifey was SAMA’s deputy governor for research and international affairs. He has since been promoted to governor of the central bank. The fact that SAMA’s paper explores a wide range of alternatives to the peg suggests that Saudi authorities are open to change.

Economists at Samba Financial Group in Riyadh argue in a recent report that Saudi Arabia’s balance of payments will sustain another heavy outflow this year, given the size of the government’s fiscal financing operations. “The situation should improve from next year onward, as oil prices recover somewhat and foreign equity inflows pick up on the back of the Tadawul’s [Saudi stock exchange’s expected] inclusion in the MSCI Emerging Markets Index,” they conclude.

The kingdom’s net foreign assets were drawn down by $115 billion in 2015, equivalent to about 18% of GDP—enough to spark concerted speculative attacks on the riyal’s dollar peg, according to Samba. “The peg plays a key role as a nominal anchor for the economy and will be an important consideration for potential foreign investors, who will become the main influence on the financial account as the government steps up efforts to liberalize the economy,” the Samba report observes.

If Saudi Arabia finally succeeds in its efforts to radically diversify its economy, the dollar peg could fall by the wayside. That is unlikely to happen for some time, however. “As long as oil is priced in dollars and a high percentage of regional GDP comes from oil revenues, it would be very costly to remove the peg,” says ADS’s Ghanem. “For this reason, we cannot see this changing in the near future.”