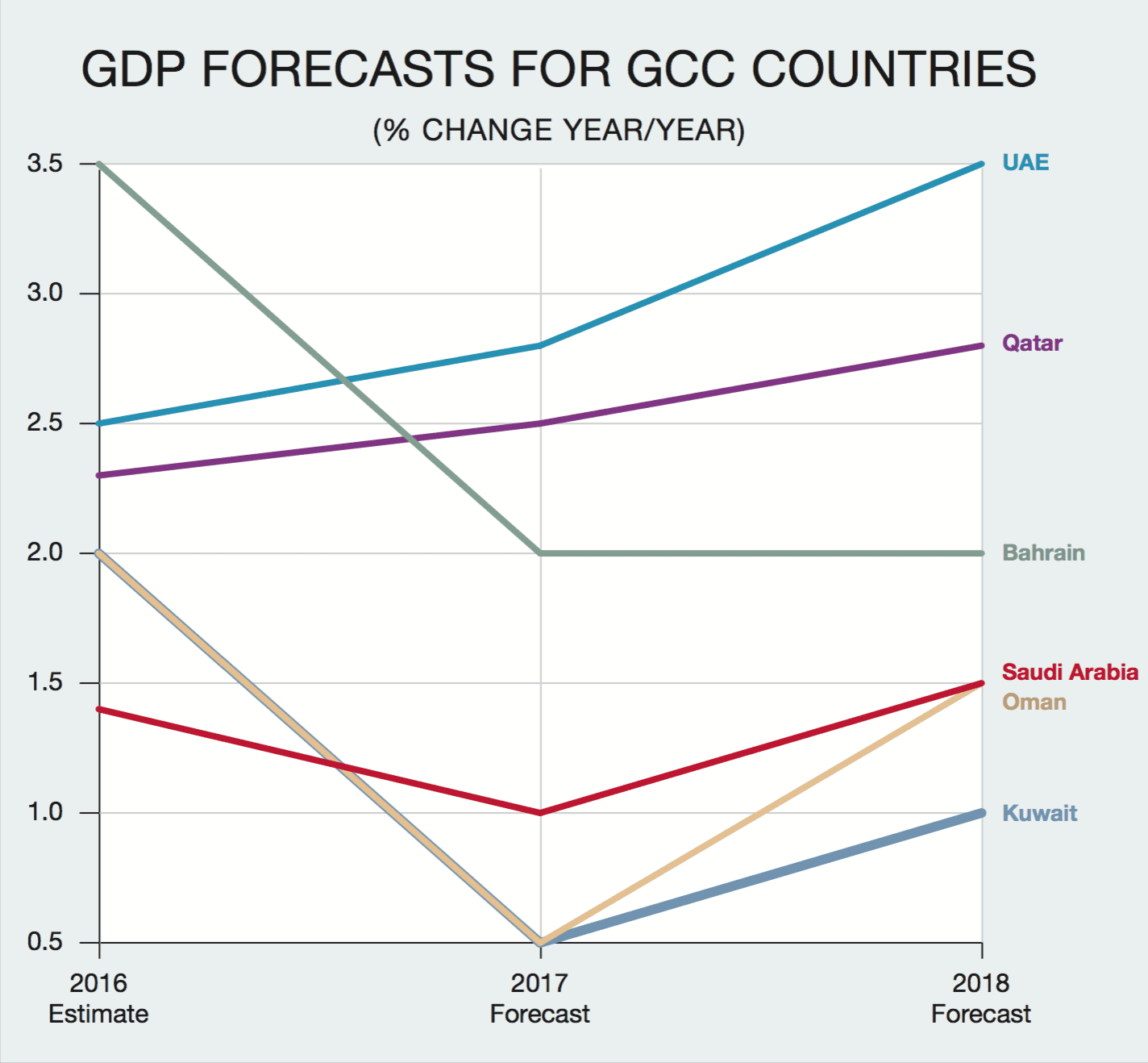

Outlooks vary by country, as leaders variously try economic diversification, austerity and financial reform.

Return to GCC Report

Oil prices continue to weaken, dropping below $50 a barrel in mid-June, despite the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ decision to extend output cuts through March 2018. Low crude prices are less problematic than in the recent past, however, for producers in the Gulf Cooperation Council, which already have made significant spending cuts and subsidy reforms.

“The countries of the Gulf are in a far better position now to weather a period of low oil prices than at any point over the past three years,” says Jason Tuvey, Middle East economist at Capital Economics in London. “Rather than resort to currency devaluations, governments across the region have embarked on a period of fiscal austerity in order to make the adjustment to low oil prices … and efforts have been made to raise non-oil revenues.”

Tighter fiscal policy has dampened domestic demand, Tuvey says, and this has filtered through into weaker imports. Current account positions have started to improve, and the drawdown of foreign exchange reserves has slowed, he says. He adds that debt levels remain low in most places, so governments have plenty of room to return to bond markets.

Commodities economists at Capital Economics expect crude could rise to about $55 a barrel by the end of 2017. They say the current weakness is largely due to concerns about persistently high US stocks and growing US production, which they expect to slow over the remainder of the year. “At the same time, strong growth in oil demand driven by higher global [economic] growth and an extension of OPEC’s production cuts should ensure that stocks fall sharply in the second half of 2017, putting upward pressure on prices,” they write in a recent report.

Saudi Arabian energy minister Khalid al-Falih told reporters on a visit to Kazakhstan in June that a drawdown in crude inventories would accelerate in the next three or four months and that the kingdom planned to boost exports to the US in the long term. Saudi Aramco, the national oil company, recently slashed its oil exports to the US as part of its efforts to reduce the global glut. The country’s crude exports to its Asian customers are also declining.

While oil production cuts are curbing the region’s economic growth, the International Monetary Fund expects growth in the GCC’s non-oil sector to rise to 3% this year from less than 2% in 2016, as austerity eases somewhat and economic diversification efforts continue. Tim Callen, who led an IMF team to Saudi Arabia in May, says the government’s aim of a balanced budget is appropriate, but should be done slowly. “A more gradual fiscal consolidation to achieve budget balance a few years later would reduce the effects on growth in the near term, while still preserving fiscal buffers to manage future risks,” he says. “Energy price reforms are a key priority, but there is scope for a gradual implementation to give households and businesses more time to adjust.”

“The [Saudi] authorities are beginning to make good progress in identifying and reducing obstacles to private sector growth,” according to Callen. This includes reduction of customs clearance times, making it easier to start a business, and moving toward completion of the new bankruptcy and commercial mortgage laws. “Additional reforms are expected, including an ambitious privatization and PPP [public-private partnership] program to reduce the role of government in the economy,” Callen says.

Natalia Tamirisa, who headed an IMF mission to the United Arab Emirates in May, says: “The UAE is adjusting well to the new oil-market realities. Its large financial buffers, diversified economy and the authorities’ robust policy responses are facilitating the adjustments while safeguarding the economy and the financial system.”

“Banks’ liquidity and capital buffers are helping them cope with lower oil prices,” Tamirisa continues. “Swift approval of the draft central bank and banking law [in the UAE] would strengthen the prudential policy framework,” she adds. “Further improving access to finance for small and medium enterprises would foster entrepreneurship and create private sector jobs, including for women.”

Nemr Kanafani, senior economist at National Bank of Kuwait, says the Kuwaiti government remains committed to an ambitious capital spending program, but that the fiscal deficit will continue to narrow this year and next. Kanafani says Kuwait’s overall GDP is likely to shrink by about 2.4% in 2017, reflecting OPEC production cuts, before returning to positive growth of 3.2% in 2018. Kanafani expects Kuwait’s non-oil GDP growth to run at 3.5% to 4% in 2017 and 2018, with the launch of major projects offsetting a slowing consumer sector. The Kuwait National Development Plan was relaunched in the first quarter of 2017.

“Kuwait continues to enjoy a relatively comfortable fiscal position, thanks to a low breakeven oil price and substantial overseas assets,” Kanafani says. “Sovereign wealth fund assets … are estimated to be near $560 billion, or 450% of GDP.” Fiscal reforms are moving ahead, and large fiscal buffers support a gradual approach to reducing the deficit, according to Kanafani. In March, the government hiked electricity and water tariffs, but by much less than was mandated in legislation passed last year.

Qatar is not a major oil producer, but it is the world’s largest exporter of liquid natural gas. The peninsular country, which is in the midst of a diplomatic dispute with its GCC neighbors, recently announced the lifting of a 12-year moratorium on the development of its offshore North Field, the biggest gas field in the world, which it shares with Iran. In addition, Qatar’s offshore Barzan field is expected to come online this year.

The availability of relatively cheap natural gas supplies is critical to the GCC’s petrochemical industry, which has grown rapidly over the last three decades. Marmore MENA Intelligence, a subsidiary of Kuwaiti investment bank Markaz, says in a recent report: “GCC petrochemical companies have achieved significantly higher margin as compared to global players. However, recently, … on account of depleting resources, … profit margins have started to decline.”

The balance of power among regional producers is shifting, the report says. “Multiple market disruptions—including the shale gas discovery in the US, low oil prices worldwide and a capacity expansion drive in China and Iran—are reshaping the petrochemical industry,” it says. “In addition, the GCC is also experiencing a regional shortage of natural gas, due to supply-demand imbalances.” The UAE relies on Qatar for 30% of its natural gas needs. An undersea pipeline operated by Dolphin Energy of the UAE carries refined gas 225 miles from Ras Laffan in Qatar to Abu Dhabi and Oman. Meanwhile, Oman’s economy is struggling, with GDP growth expected to grind to a halt this year before picking up to about 2% in 2018. “With domestic gas demand [in Oman] still outstripping supply, and the bulk of gas output going toward Oman’s LNG exports, the need for gas imports continues to grow,” according to the National Bank of Kuwait.

Global oil supplies remain in a glut, despite the output cuts by OPEC. Still, most GCC countries can look forward to GDP growth improving in 2018.