Telecoms and local start-ups are bringing digital banking to underserved areas of the continent, often in partnership with traditional banks. But working together isn’t always easy.

The majority of Africans remain unbanked, without any access to financial services. This is widely seen as a serious drag on economic development and job creation. But it also presents an opportunity for fintechs, telecommunications operators and banks keen to bypass legacy structures and roll out mobile-banking solutions that are cheaper and better suited to local conditions.

“In the broader African context, fintechs and mobile operators have the advantage, as everything is leapfrogging to data-mobile solutions,” says Michael Jordaan, co-founder and chairman of the South African all-digital challenger Bank Zero, “whereas banks are still very much reliant on face-to-face processes, mostly branch-based, for acquisition and servicing.”

Extending financial inclusion across the continent could happen faster once banks and technology companies recognize the need to cooperate more closely. As the saying goes, it takes two to tango. But while the orchestra has struck up, the dancers are still at the initial stage of circling each other, torn between attraction and restraint.

The opportunity is there. Sub-Saharan Africa has the fastest-growing mobile-phone subscriber base in the world, according to The Mobile Economy: Sub-Saharan Africa 2019, a recent report by the GSMA, the mobile operators’ trade association. By the end of 2018, nearly 400 million mobile-money accounts in the region were registered with over 130 live mobile-money services.

Expanding access to financial services and e-commerce is among the key aims behind the World Bank’s decision to back Africa’s digital transformation with an investment of $25 billion between now and 2030, which it hopes will be matched by the private sector.

A joint fintech agenda from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund calls for countries to “enable new technologies to enhance financial service provision.” While underlining downside risks for vulnerable customers, such as data breaches and excessive borrowing, the report concludes that technology-based solutions are more efficient, reduce costs and can rapidly be scaled up.

Most of the potentially disruptive fintech platforms are being developed by local tech start-ups, according to the GSMA report. And Alex Vines, research director for Risk, Ethics and Resilience at London-based think tank Chatham House and head of its Africa program, thinks “African innovation will become more significant globally in the long term.”

Vines sees established hubs like Nairobi, Cape Town, Lagos and Accra expanding rapidly and distancing themselves further from potential competitors—thanks in part to their magnetic attraction for human talent nurtured elsewhere. These centers also have a business base large enough to help start-ups raise the capital needed for scaling up, and subsequently to protect them from predatory governments.

This “critical mass” is essential, says Vines. “Many entrepreneurs in countries like Zambia, Tanzania and Uganda don’t scale up, because that would only attract the unwanted attention of the political elite.”

While recognizing that local tech companies are often best at reaching out to rural areas and coming up with solutions specific to local conditions, Sanyade Okoli, CEO of Lagos-based Alpha Africa Advisory, says that “for fintechs to be successful and sustainable in the long term, there needs to be a viable business model.” Just as with tech entrepreneurs in other parts of the world, “with some tech start-ups, it’s not always clear where the revenue streams are coming from.”

Greater Opportunity

The lower the level of financial inclusion in a country, “the greater the opportunities for fintechs—and consequently the more likely that the regulator will take a tolerant view of the range of their activities,” says Chris Steward, a portfolio manager at Cape Town–based Investec Asset Management. That is certainly true in Kenya, where dominant telecom player Safaricom pioneered mobile payments and has struck deals with banks including Commercial Bank of Africa and KCB Bank, allowing them to lend to customers and take deposits via an M-Pesa platform.

Not all these relationships run smoothly. Nine years ago, Safaricom teamed up with Kenya’s second-largest lender, Equity Bank, to launch the M-Kesho mobile-banking app, but the initiative flopped amid disputes over revenue sharing. This year, the two parties decided to revive M-Kesho through a new partnership whose stated aims are to enhance access for young people and rural communities.

As a licensed bank, Equity’s role is primarily to tackle regulatory barriers to the mobile platform’s ability to take deposits and make larger loans. In the future, it also hopes to leverage its strong regional presence to expand M-Kesho into neighboring Tanzania, Rwanda and Uganda, where rival M-Pesa has no presence. But since Safaricom has more than twice the number of customers and controls the means of distribution, it is clearly the senior partner. Equity Group has come to “a humble acceptance that Equity is a subset of Safaricom,” says CEO James Mwangi.

When it comes to alliances between telecom operators, fintechs and banks, the bigger, the better. This is likely to be the case in Nigeria, where the dominant mobile group MTN has been granted a superagency license to offer a limited range of mobile payments and money transfers. With access to a huge pool of potential customers currently using its voice services, MTN will pose a challenge to Nigeria’s traditional banks and to its largest fintech company, Paga, whose more than 12 million users are serviced by a network of 14,000 licensed agents. Moreover, MTN has the financial firepower to set up its own network and compete on price with Paga and other fintechs, which have focused primarily on peer-to-peer transfers or bill payments.

“The superagency license permits only a restricted range of products and functionality,” says Steward. “To progress further, you need a full banking license from the central bank, which has made only slow progress, partly because of its bureaucratic processes but also because it may want to license several operators at the same time so as to create a competitive market.” Incumbent banks might also be trying to delay the licensing of new rivals.

Most central banks in Africa have been cautious about granting fintechs broader licenses because, as Steward notes, “once deposit-taking is included in their suite of offerings, they effectively become custodians of the nation’s savings and therefore need to be regulated like any other bank.”

Relationships between banks and new fintech start-ups are few and far between, says Bank Zero’s Jordaan. “The only exceptions are those where the fintech needs access to a banking license as it engages in deposit-taking activity, or where the large banks effectively buy innovation.” Since fintechs are generally positioned as challengers to incumbent banks, banks may fear an open partnership would cannibalize their own products and customer base.

There are also cultural reasons for the current standoff. “Big banks, like most corporations, have immune systems that attack outside ideas using antibodies,” Jordaan quips. “Small, informal, young, focused start-ups differ markedly from the typically more formal, process-driven, decision-by-meeting banks.”

In South Africa, the dominance of traditional banks has largely kept fintechs on the periphery, offering customer-friendly innovations in payments, money transfers and remittances, says Steward. But lately the emergence of upstarts offering a more-comprehensive suite of banking products has been like “a full frontal assault” on the Big Four incumbent banks.

“The challengers have the potential to enjoy a significant cost advantage, as they can offer transactional banking services with an off-the-shelf core banking system quicker and cheaper than traditional banks,” Steward says. “This allows them to provide free or very low-cost banking, while offering attractive levels of interest to customers that switch to them.”

The incumbents have responded by lowering bank fees and, in some cases, raising interest paid on deposits. They have been closing branches and investing heavily in IT as more of their clients migrate from physical to digital channels. “They are under pressure,” says Steward, “as their revenues are currently being eroded faster than the cost savings are kicking in.”

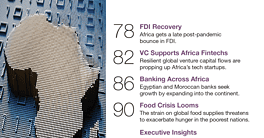

The standard response by traditional banks in South Africa so far has been “either to emulate what [fintechs and challenger banks] are doing in-house, or to go out and acquire a fintech and bring its expertise in-house,” he says. The result: few open and meaningful tie-ups between the big banks and fintechs to date.