Public and private sectors vie for reform in an energy sector tug-of-war.

When Andrés Manuel López Obrador (known as AMLO) was elected president of Mexico in 2018, he promised to curtail the ongoing privatization in his country’s energy sector. Almost three years and many canceled private permits later, Mexico faces a feud between private and state-owned companies that are likely to shape the industry’s future in the region.

For eight decades, Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) in the oil and gas industry, and the Comision Federal de Electricidad (CFE) in the electric industry, controlled the Mexican energy sector as state-owned monopolies—a business environment that led Pemex to become the second-largest oil company in Latin America, after Brazil’s state-owned Petrobras.

With an acute shift in policy in 2013 and 2014 under the administration of then-President Enrique Peña Nieto, the country enacted the Electric Industry Law (LIE) and the Hydrocarbons Law (LH), which opened the energy sector to free-market competition through auctions for concessions in both sectors.

Peña Nieto also gave powers to two previously existing third-party commissions, the Comision Reguladora de Energia (CRE) and the Comision Nacional Hidrocarburos, to enforce so-called asymmetric regulation between the country’s public and newly created private sectors. This measure aimed at limiting any state-owned company’s market position through regulatory obligations, thus creating a level playing field for private companies.

Taking advantage of the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) while eyeing Mexico’s large unexplored potential, global giants such as Eni, Fieldwood Energy, IEnova, Iberdrola, ExxonMobil, Chevron and others poured massive amounts of investment into the country. In the power sector, change was so swift that in 2018, 45% of the country’s electric power was generated by private companies. Pemex’s market share significantly decreased in fuel imports as well as in midstream and downstream industries.

AMLO Pushes Back

But then came the backlash, as López Obrador took office in December 2018 with the promise at the center of his nationalist political agenda of reclaiming Pemex’s and CFE’s historical dominance. While not vowing to reinstate state monopolies, he made a series of regulatory changes that negatively affected private-sector participants.

First, he suspended pending auctions for new exploration and production licenses and launched a review of more than 100 previously awarded permits. “We are open to negotiation [but] we have to review these excessive contracts,” he has often said.

The bulk of López Obrador’s policy came into effect in 2021, when he passed modifications to the LH and LIE through Congress. First, the modifications gave Mexico’s government “discretionary powers to suspend permits of private companies for unspecified reasons of national security, energy security, the national economy or, where applicable, for violation of laws and permit terms,” according to a report by law firm Morgan, Lewis & Bockius. Second, they removed the CRE’s power to impose asymmetrical regulation in the market. Moreover, his administration cut the agency’s budget by over 70% between the start of his administration in December 2018 and January 2021.

But the most problematic part of López Obrador’s reform was an amendment that supposedly gave the government the power to allow a productive state enterprise—such as Pemex or CFE—to take over facilities whose permits were suspended. A flood of legal actions in domestic courts followed these measures. Claiming the protection of the right to free competition, a Mexican federal judge suspended López Obrador’s LIE indefinitely. Foreign companies are also seeking to invoke the many longtime international commerce agreements that legally protect investments in the country, but they must wait for a decision in domestic courts first. The US Chamber of Commerce has already stated that AMLO’s measures “directly contravene Mexico’s commitments under the [USMCA].”

There are no indications that private investment in the sector will be prohibited. “The main deterrent for investment in the country is related to the lack of clear government signals on the participation of the private sector throughout the entire energy sector, including power [solar, wind and natural gas], as well as the upstream, midstream and retail sectors,” says Jaime Brito, Vice President at energy consultancy Stratas Advisors. “The current administration has openly stated that Pemex and the national power entity, CFE, need to play the dominant role in their corresponding markets, which has gradually translated into a more challenging commercial environment for private companies that do not own storage, pipelines or port infrastructure.”

Currently, Mexico’s power generation relies almost solely on petroleum (and other liquids) and natural gas, which contribute 43% and 42% respectively, according to the US Energy Information Administration. The remainder comes from coal (7%), renewables (4%), hydroelectricity (3%) and nuclear (1%).

All of Mexico’s crude oil comes from domestic production. Nonetheless, the country imports most refined products, such as fuels, from the US via Pemex. This is mainly due to the lack of refineries in both private and state sectors and the USMCA, which makes importing financially attractive. Mexican law also forbids private crude oil imports, forcing midstream and retail players to purchase large volumes from Pemex.

This also gives Pemex the upper hand in pricing. As a historical policy, the state-owned company does not necessarily distribute international price variations to the end consumer, undermining competition while keeping gas prices artificially lower whenever its management decides to do so.

“Global price increases do not necessarily permeate to the Mexican upstream sector, as the country lacks infrastructure for private production to export to international markets,” says Brito. “So, private companies in Mexico sell their barrels to the national oil company, Pemex, not necessarily capturing daily international price variation.”

A similar challenge is perceived in the natural gas industry, which accounts for 61% of the country’s electric power. Currently, imports coming from the US-Mexico pipeline amount to an astonishing 76% of the market, in a network that the CFE and Pemex controls.

“Mexico’s biggest opportunity, by far, will be to allow crude imports,” Brito adds, “as it will be an option that will enable optimization of the crude slates and increasing refinery runs, which would reduce fuel imports.”

Energy’s Bright Future

Many in the industry believe public-private partnerships can overcome infrastructure gaps and reduce the need for imports. “The government has a valid point in wanting to strengthen the already-battered Pemex and CFE,” says Ricardo Falcón, senior gas analyst for Mexico at energy research and consultancy firm Wood Mackenzie. “But this should not be at the expense of much-needed private investment.”

Mexico also has a largely unexplored potential in renewable energy, but López Obrador’s policy seems wholly focused on hydrocarbons to promote Pemex’s dominance, according to Brito.

“The long-term trend will aim to reduce the carbon footprint, but this will certainly take place at a slower pace in Mexico, given the economic, social and infrastructure,” he says. “Whereas most developed economies are aiming to implement regulation and investments to move away from hydrocarbons, there are regions in Mexico where the population has not had an opportunity to consume hydrocarbons yet.”

Although political and regulatory uncertainty keeps driving direct foreign investment away from the country, some claim there is a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. “Mexico is not entirely closed for business,” says Duncan Wood, vice president for strategy and new initiatives and senior adviser to the Mexico Institute at the Wilson Center in Washington, DC. “The energy sector still offers extraordinary opportunities. Different actors are finding different opportunities in that space.”

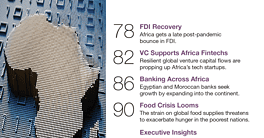

Demand for energy almost never decreases, placing the sector’s in a privileged position for substantial growth in the foreseeable future. But salvaging investor confidence in the country could all come down to whether the private and public sectors can reach a mutually beneficial consensus for the long run.