African citizens voice concern about government use of large resources in failed infrastructure projects.

In May, at a ceremony to mark the inauguration of a new $3 billion deep-water port in Lamu, a fraction of the wider Lamu Port South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport Corridor Project (total estimated cost $24 billion or more), Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta was at pains to defend the viability of the project: “Those who doubt its viability, just as they doubted our ability to build it, will … be put to shame.”

The need to defend the project was evident. Despite the ceremony, only one of three planned berths had been completed, at a cost of $367 million, with none of the necessary associated infrastructure. Kenya has asked for an additional $157 million to complete just this phase of the project. Furthermore, the project is financed by Chinese loans, which Kenyans have castigated for plunging the country into a debt abyss. More critically, local consensus is that the facility bears the hallmarks of a white elephant.

President Kenyatta’s predicament is not an isolated case. Various African governments have faced backlash for pumping massive resources into dud infrastructure projects, some of which have stalled midway. And while the continent has been on an infrastructure-building boom to spur economic growth over the past two decades, the jury is still out on whether African nations have engaged in well-thought-out and sustainable projects that have significant economic impact.

“The quality and efficiency of the investments have not always been as intended,” reckons Kannan Lakmeeharan, a partner at McKinsey’s Johannesburg office. “This created challenges around debt service and realization of the desired benefits.”

To be sure, some countries have seen great success with infrastructure development as a catalyst to growth. In 2015, Egypt invested $8.5 billion to expand the Suez Canal, which generated $5.6 billion in revenue last year and already more than $3.9 billion this year as of late August. The country has committed about $50 billion to revamp its centuries-old transport infrastructure. On top of boosting GDP growth—averaging 4.7% over the past four years despite last year’s Covid-19 slump—the effort has significantly raised the quality and availability of transport, particularly in major cities.

The same cannot be said everywhere, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, which has struggled to build stable economies. During the early years of independence, growth was pegged to the agrarian revolution; yet Africa remains food insecure and a net importer of food, to the tune of $35 billion in 2020, according to the World Bank. Hopes then shifted to industry, but today most sub-Saharan countries still export raw materials and import finished goods.

Now infrastructure is only the latest great hope. From the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the Program for Infrastructure Development in Africa—an initiative of the African Union Commission, the New Partnership for Africa’s Development, and the African Development Bank—to individual country masterplans and blueprints, the push for investment in roads, railways, ports, airports, energy, information and communications technology companies, water and sanitation and more has been unprecedented.

“It is good thing African countries are prioritizing infrastructure developments, because they will most definitely spur economic growth in future,” says Wildu du Plessis, Johannesburg-based partner and head of the global Africa practice at Baker & McKenzie. He notes the challenge for the continent is that the scale of infrastructure gap remains colossal. Closing a financing gap of $53 billion to $93 billion annually, according to African Development Bank estimates, is paramount.

There are good reasons why the continent is prioritizing infrastructure development. For other sectors to thrive, they need functional enablers. Building of roads, for instance, is critical in enabling smallholder farmers’ access to markets; while electricity and internet access inspire innovations. For countries to integrate, cross-border links like railways and electricity transmission lines are a necessity. Ethiopia, for instance, is banking on the East African Power Pool project to increase electricity sales to neighboring countries upon completion of the controversial $4 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Africa also needs success of the trade integration that will be brought about by the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement. For this to happen, critical infrastructure projects must be implemented. These include the Trans-Maghreb Highway in North Africa, the Trans-Sahara Highway, the North-South Multimodal Corridor, the Central Corridor project and the Abidjan-Lagos Corridor Highway project, among others.

“Investment in African infrastructure is a global public good,” states a 2020 report published by the African Center for Economic Transformation and the OECD. Taking into account the continent’s demographic evolution, infrastructures are a necessity in making crosscutting sectors productive. For Africa, this is a matter of urgency. High rate of population growth and urbanization is already exerting significant pressure on existing infrastructures. This means “Africa is facing a monumental task to prioritize, accelerate and scale up quality infrastructure development,” notes the report.

Herein lies the challenge. Failure to plan properly in the past has meant a majority of nations have amassed substantial amounts of infrastructure-related debts, mainly to China, the continent’s largest bilateral lender. China Africa Research Initiative data shows the Asian giant has committed $153 billion in 1,141 projects in Africa over the past two decades. Power and transportation projects account for about 55%.

Tragically, servicing these debts has become a huge burden. The challenge is exacerbated by the fact that some of these projects are not delivering the desired benefits. Kenya and Ethiopia are classic cases where Chinese-funded standard-gauge railway projects are struggling to break even, inducing substantial pain in repaying debts cumulatively amounting to more than $6 billion.

“China reiterated it wants to be considered a responsible investor in Africa,” observes du Plessis. Debt-squeezed nations are worried stiff about the long-term effects of the accumulated debt. This includes directing most of their revenues to service debts at the expense of development expenditure, leading to ratings downgrades that make it hard to borrow. Zambia has defaulted, while another six countries were in “debt distress and 14 others were at high risk of debt distress as of December 2020,” according to the AfDB.

The situation is worsened by the fact that China’s lending to the continent is declining. According to IJGlobal figures cited in a report published in April by Baker McKenzie, Chinese banks’ lending to African energy and infrastructure projects peaked at $11 billion in 2017. It plunged substantially to $4.5 billion in 2018 and $2.8 billion in 2019 before a small uplift in 2020 to $3.3 billion.

The new reality calls for countries to be creative in mobilizing financing for future projects, which must also be watertight in terms of long-term economic benefits. “There is an increasing focus on longevity and sustainability in infrastructure finance. This is driving a rethink of the investment calculus: that deals should be net positive for local economies as well as bankable,” notes du Plessis.

It is obvious that commercial banks cannot fill the funding vacuum. Apart from global financial development institutions, the continent must cast its net wide to include private equity, debt finance, specialist infrastructure funds and even the private sector to mobilize funding. In the private sector, innovative public-private partnership models must be formulated.

“The private sector would want to ensure an adequate risk-reward trade-off,” avers Lakmeeharan. He adds that in many cases, the private sector feels the risk premium makes the project unbankable.

With the bandwagon of infrastructure-led economic growth showing no signs of a slowdown, Africa has no options but to make projects bankable. The continent must also find a solution to the tumor that makes “80% of projects fail at the feasibility and business-plan stage,” as McKinsey reported last year. This is a problem largely caused by inadequate attention to portfolio planning, prioritization and clarity on what would make a project fundable.

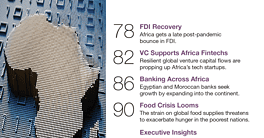

Getting the infrastructure development matrix right is undoubtedly central in transforming Africa into the global powerhouse of the future in line with Agenda 2063 ambitions.