Checking in on the AfCFTA, launched in January to forge a united African market.

After a six-month delay due to Covid-19, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) finally took effect in January. With more countries than any other regional free trade area, it aims to be a model of cross-border cooperation in an era of growing isolationism. The World Bank proclaimed that “it has the potential to lift 30 million people out of extreme poverty.”

Although home to 1.2 billion people, “Africa accounts for just 2% of global trade. And only 17% of African exports are intracontinental, compared with 59% for Asia and 68% for Europe,” says the World Economic Forum. With advances in digital technology, small and midsized enterprises (SMEs) seem well placed to benefit from the pact and help boost employment. The potential is enormous. But so are the challenges. The implementation stage has only begun. Some pundits worry that it will be yet another failed promise.

“It is groundbreaking and potentially transformational,” says David Ofosu-Dorte, an Accra-based senior partner at African law firm AB & David. “But whether it will achieve its objectives is another matter.”

“It is transformational for multinational companies and for SMEs,” says Geoffrey White, CEO for Africa at global logistics provider Agility. “If your market is in Ghana and you want to move to Côte d’Ivoire, it is incredibly expensive [now]. [With AfCFTA], Africa is going to begin to compete—in theory.”

Five years of negotiations led to the signing of the agreement in 2018. All but one (Eritrea) of the 55 member countries of the African Union signed on. By early September, 38 had ratified the deal. Originally set for mid-2020, the official launch date was postponed for six months due to the Covid-19 crisis. “It is a huge step forward, but they lost a huge amount of momentum due to Covid-19,” says William Pollen, program director at Invest in Africa, a nonprofit that works with SMEs.

The terms include tariffs falling to zero over the next decade on 90% of the goods traded and liberalization of regulations on service sectors including finance, communications and tourism, according to a white paper released in August by British Arab Commercial Bank (BACB). Signatories were tasked with drawing up proposed rules of origin. As of April, most had done so, according to a report by Virusha Subban, a partner in the Johannesburg office of the law firm Baker McKenzie.

There are discussions about temporary duties. Some countries, especially smaller, more vulnerable ones, are mulling it over. “In the case of Mozambique, we are still studying how to make an offer,” says Kekobad Patel, a board member of Mozambican trade technology partnership, MCnet and a member of the policy board for the Confederation of Economic Associations of Mozambique (MCnet). One possibility would be to maintain higher duties for three years followed by gradual reductions.

The accord was launched with a huge amount of fanfare, but sober minds have begun to think about the challenges. “Africa is a vast and diverse continent, but the obstacles to furthering trade integration across the region are often surprisingly similar,” notes the BACB white paper. “Hard and soft infrastructure—not only for the physical transportation of goods, but also for financing trades, facilitating payments and exchanging currencies—can be lacking, and require substantial investment.” As Pollen notes, “They need to manage expectations. They didn’t help themselves by hyping it.”

Everyone recognizes the richness of Africa`s natural and human resources. But severe barriers block the region from taking advantage of them. The main issues are logistics and infrastructure, bureaucracy and leadership.

Just lowering duties won`t be enough. “Nontariff barriers—such as access to finance, poor rail and road infrastructure; and logistical elements such as customs duties, excessive border regulations and port congestion—have also played a large role in impeding growth in volumes and continue to threaten the AfCFTA’s success,” says the BACB white paper.

Anyone who has tried to travel from one African country to another understands how complicated the logistics can be. Travelers often must go to Europe to make connections within the continent. The same goes for goods. According to BACB’s research, the flows of African trade are still mired in historical precedent dating back to the colonial era, when coastal seaports connected African nations to external partners. “Goods still largely follow these established routes today—predominantly to Europe, the US and Asia,” the BACB finds. “Infrastructure linking African neighbours remains poor.” Agricultural goods traded between Tunisia and Cameroon, the authors offer as an example, often transit through French warehouses on the way from African farms to African supermarket shelves.

Perhaps flying under the radar, African countries have been taking steps to address these problems. Negotiations continue apace to establish a Single African Air Transport Market. Projects such as the Cairo to Cape Town corridor, the Djibouti to Dakar railway and the Abidjan-Lagos transport corridor would make it much easier to get from here to there. These developments are often ignored when people talk about the future of the pact. “There is an ‘Africa beneath’ and the Africa that makes the news,” says Ofosu-Dorte. “The ‘Africa beneath’ doesn`t make the news.”

Yet just having a road isn’t enough; and there, too, lie opportunities. “If a South African firm wants to export to Tanzania, it has to go through Mozambique and Malawi,” observes Patel. “You can`t just open trucks at the border, because of the cost. We need electronic systems that can scan quickly.” Logistics needs are opportunities. Pollen points out the emergence of e-logistics firms such as Kobo360 in Nigeria and Lori Systems in Kenya.

Paperwork and border delays can make it too costly for companies to export even to their closest neighbors. “The tax authorities and the technocrats are the biggest holdups sometimes,” says Monica Musonda, founder and chief executive of Java, a Zambian food company. While she might want to trade with the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, she finds it can be cheaper to get materials from Europe. “We need to resolve that,” she says. “We need standardization.”

While sometimes “left in the dark” in initial stages, as Musonda puts it, the private sector has become enthusiastic about the agreement. “This is the first time that the private sector has popped the champagne over an initiative of the African Union,” says Ofosu-Dorte.

But if people don’t see results, the enthusiasm could wane. Africa has seen its share of much hyped but ultimately disappointing initiatives. “If countries get defensive and don`t remove barriers, the momentum will be lost,” says Patel.

Which begs the question of leadership. Many African observers noted that the European Union, while imperfect, has moved along, in large part due to the leadership of Germany and France.

Who will play that role in Africa? Ghana has agreed to host the AfCFTA’s secretariat in Accra and created a media event to call attention to the first two export deals under the accord, both involving Ghanaian companies. Most observers believe that heavyweights such as Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa will need to make their presence felt.

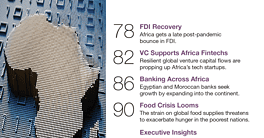

Or perhaps not. “We lack a Germany to pull things along or a France as the center of the economy,” says Ofosu-Dorte. “But we have demand from the private sector to see that this is done and done right. In soccer terms, this is not a team with one or two stars, but one with enough good players so that we may achieve our goals.”