African nations seek to scale the value ladder, moving beyond cheap labor and commodity exports. That takes steely commitment.

Calls for economic diversification have gone on for decades in African countries. However, only some have matched their words with actions.

Africa’s performance on diversification has been poor because it requires a strong political will to implement, says Gaimin Nonyane, head of economic research at Ecobank, the pan-African lender. “Whether you have a policy in place or not, whether you have infrastructure or not, if you don’t have a strong political will to drive it, then the impact will be limited.” In Africa, governance is “very weak,” she adds.

In Mauritius, Africa’s shining example of diversification, such a political will has worked well. Although it has a cheap labor force, employed primarily on sugar plantations, that’s a weak comparative advantage. Seeking to attract foreign investors, the government sought to identify incentives to entice such investors into other labor-intensive industries. The government removed taxes on profits, dividends, capital gains, exports and raw material imports, drawing a flood of investors from China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Taiwan and Europe.

“Once we allowed foreign investors to tap our labor force and produce their output for export, we gave them all the incentives,” says Kee Chong Li Kwong Wing, chairman of SBM Holdings, the second-largest company on the Stock Exchange of Mauritius. “We have been able to create so many jobs for our labor that we are now in short supply, and have to import labor.”

These policies have also altered the country’s export structure. Until the late 1970s, sugar accounted for up to 98% of exports, according to Wing; this is now down to just 5%. The export list now includes tourism, textiles and textile-related products, financial services, luxury goods and other services.

On the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is making progress as it diversifies from agricultural products into manufacturing and services, attracting some Chinese companies to produce shoes for export. This success is due in part to the stability that Ethiopia enjoys and the political will that drives it, Nonyane says. What remains for Ethiopia, she adds, is the need to open up or liberalize some of the sectors that can attract more investment.

For its part, Botswana is diversifying along the value chain. Rather than exporting raw diamonds, Botswana has developed diamond polishing and marketing hubs to keep added-value work.

In East Africa, Kenya stands out for major strides in financial services, telecom, horticulture and tourism. The government established the Horticultural Crop Development Agency, which has become a major foreign-exchange earner. “This is a direct policy targeted at a sector identified to have huge potential,” says Razaq Ahmed, chief executive officer of CowryWise, a Lagos-based fintech.

In southern Africa, two countries, South Africa and Botswana, have also made good strides. Riding on three critical factors—infrastructure, access to finance and prior decades of good leadership—South Africa is diversifying from mining to services such as finance and telecom, as well as manufacturing and agriculture.

Most impressive, perhaps, is that Rwanda, 23 years after it was devastated by a genocide in which more than 800,000 people died, has emerged as a good example of diversification. President Paul Kagame demonstrated strong leadership shepherding Rwanda’s rise from the ruins, Nonyane says, pulling away from agriculture to services and manufacturing.

This has had significant impact on the economy: It achieved average real growth of about 8% between 2001 and 2015, according to the World Bank.

Landlocked and small, Rwanda’s economies of scale are limited. Yet its people have a remarkable work ethic, according to Nonyane.

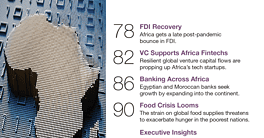

“This is a country that has a more disciplined way of life than most African countries,” she says. “People wake up early on Saturday morning just to clean their streets.”