The regional economy is expanding, but a global slowdown and a continuing infrastructure deficit stand in the way of faster growth.

Africa is now among the world’s fastest-growing economic regions after Asia—and the gap between them is narrowing, as China’s economy cools in the shadow of a trade war with the US. Many African economies are in robust shape today thanks to fiscal restraint and a buildup of foreign currency reserves. A global economic slowdown, however, would be felt across the continent.

“Africa is not an island,” says Chris Steward, head of financials at Cape Town–based Investec Asset Management, “and its many diverse economies are not immune to the impact of changes in the rate of global growth and the commodities cycle. That said, each economy is unique and will be uniquely impacted by developments in this regard.”

Economic growth across the continent is expected to continue accelerating to 4% this year, according to the African Development Bank. It notes that this average figure would be much higher if not for the drag of the two largest sub-Saharan economies, South Africa and Nigeria.

Much of the growth is being generated by a cluster of medium-size economies—Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire in West Africa, and Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda in East Africa—which have been enjoying 5% to 8% increases in GDP. The fastest-growing economy is Ethiopia, with a population of nearly 113 million and a business-friendly government pushing through market-friendly measures. Despite being a poor country, Ethiopia has “enormous potential,” says John Ashbourne, a senior emerging-markets economist at Capital Economics.

The divergence between big natural-resource exporters like Angola and more balanced, human resource–driven economies will only increase in coming years, according to FocusEconomics. Regional differences will also become more marked; East Africa is expected to achieve annual growth of near 6%, while southern Africa and Nigeria are set to expand more slowly.

Those trends could be accentuated, Ashbourne says, by worries about a global downturn, which could further depress commodities prices. Risk aversion, meanwhile, “could put a brake on foreign direct investment [FDI]” into Africa. “You see that already happening in South Africa, the continent’s most open and sophisticated economy, with capital outflows and weakness in both the rand and equities.” Most countries have less-open economies, “and are therefore less vulnerable to capital market flows,” he adds.

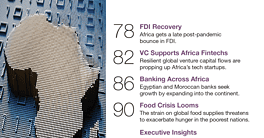

In Search of FDI

Overall FDI into sub-Saharan Africa rose by 13% to $32 billion last year, according to the World Investment Report 2019 by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. And while the continent’s biggest investors have typically been France, the Netherlands, the US and the UK, that is set to change. “China will become the prime source of FDI over the next few years,” says Alex Vines, research director for Risk, Ethics and Resilience at London-based think tank Chatham House and head of its Africa program, “though other countries including Japan, India and the Gulf States are increasingly active.”

US investment “has contracted slightly compared to 10 years ago,” Vines adds, “and is now more focused on countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, that hold strategic metals like cobalt and rare earths.” A post-Brexit Britain, on the other hand, “wants to be the largest source of FDI into Africa out of all the G7 nations.”

A further boost to FDI could come from the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), now nearly universally adopted following Nigeria’s adherence in July. “The first stage was accomplished quicker than expected,” says Vines. “Now comes the implementation—actually reducing bottlenecks at borders and other trade barriers. That is likely to be a slow, uneven process. But eventually it will result in greater economic growth coming from intra-African trade flows.”

The main beneficiaries, he predicts, will be larger economies like Nigeria. Enhanced intra-African trade would boost value-added industries and create more jobs—but the full benefits won’t come through until the necessary transport and logistics infrastructure is built. “Infrastructure is crucial,” says Sanyade Okoli, CEO of Lagos-based Alpha Africa Advisory. “It’s all very well for governments to sign up to AfCFTA. But unless you have the necessary infrastructure in place, it’s only a piece of paper.”

In Nigeria’s case, shoddy infrastructure means the cost structure for consumer-products companies is often too prohibitive for them to be able to compete in exports markets elsewhere on the continent, Okoli points out. And while governments have previously taken a controlling lead in big-ticket infrastructure projects, “they should focus more on creating the enabling environment for private-sector participation.”

Africa labors under a huge infrastructure deficit that would require another $130 billion to $170 billion investment every year just to keep up with demand. Potential investors have held back, blaming governmental rigidities for restricting the number of viable projects.

Debt Overhang

Capital inflows are further restricted by concerns about the impact of a global economic slowdown on revenues for African commodities exporters and their ability to service their debt. Fitch Ratings recently warned that sub-Saharan countries that benefited substantially from multilateral debt relief between 2001 and 2015 have since borrowed so much money that they risk falling back into financial distress.

With countries like Zambia currently struggling to finance their debt, the problem is largely attributable to their own governance practices, says Richard Ladbrook, Cape Town–based portfolio manager at Investec. “They need support from the International Monetary Fund. But to date, they have been unwilling to reach out, perhaps because of potential conditionality on fiscal and monetary policy.”

Other countries with debt-servicing issues include Mozambique—although risks there are declining, Steward says—and Angola, which suffers from high inflation, chronic lack of financial transparency and heavy dependence on oil. Rwanda is another country with sizeable deficits, although they appear manageable thanks to robust levels of internally generated economic growth.

Many African governments are benefiting from the low or negative interest rates in many developed nations, which has attracted yield-seeking investors and brought substantial growth to the eurobond market for African sovereign debt. While much of this is in foreign-currency-denominated instruments, Ladbrook notes rising investment in local-currency bonds that offer rates well above inflation—around 9% on a 10-year South African bond, for example.

The catch is that with local-currency bonds, the investor takes on the risk of any future currency depreciation and the possibility of lower credit ratings. Two major agencies have already demoted South Africa’s debt from investment grade; a broader wave of downgrades would trigger automatic outflows from the bond market. And further currency weakness would limit governments’ scope to provide further economic stimulus, and ripple through other African sovereign debt.

Bridging the Gap

“Many countries have not benefited from the 10-year commodities supercycle, due to governmental mismanagement,” says Steward. Bold initiatives such as the AfCFTA and the nascent West African currency union aim to bring about greater economic convergence. But at present, a widening gap remains between stable, well-governed countries with diversified economies and those more reliant on commodities and subject to predatory regimes or internal conflict.

“It is not so much about whether Africa is rising or declining,” Vines observes. “It’s more about how its parts are diverging.”